Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Tabor Robak and Nico Epstein: Reflecting on Digital Artistry and 'Broken Printer'

Tabor Robak is an American digital artist, renowned in the field of new media, whose work is characterised by multi-channel video installations and generative artworks.

Nico Epstein is a curator, art historian and art advisor with a deep interest in digital art. He is curating Tabor Robak's latest series of work, 'Broken Printer', presented as part of the Verse Solos program.

Having worked together many years ago, they took this opportunity to look back through Robak's artistic practice and highlight some of his most impactful work throughout his career. This was a conversation held over Twitter which has been transcribed for documentary purposes.

NE: My name is Nico Epstein. I'm an art advisor, educator and a curator for Verse. Today I have the incredible privilege of presenting Tabor Robak. From the earliest stages of his career, Tabor has been fascinated with the limitless possibilities offered by digital tools and media. His mastery over software and digital platforms allows him to craft vivid, hyper realistic landscapes and environments.

That are not just seen, but felt, enveloping the viewer in a completely immersive experience through his art. Tabor explores themes of technology, video game, aesthetics, and digital culture, inviting us to reflect on the increasingly blurred lines between virtual and physical realities. Tabor's work is not merely a display of technical skill, but a profound inquiry into the nature of existence in our digital age, and each piece that we'll go into today serves as a portal to alternate realities, urging us to question the role of technology in shaping our identity, our society, and our future.

Having made art for many years, Tabor's career spans more than 100 exhibitions in 23 countries. His work can be found in permanent collections including the MoMA in New York, the Serpentine in London, the AKG in Buffalo, the NGA in Victoria, and many more. We have an exhibition opening on April 4th which is called ‘Broken Printer’, but before we discuss that in a later conversation, the idea of this particular, Twitter space is to discuss table's career and bring his work into the web3 vernacular by contextualising and cross referencing various milestones in his career.

My relationship with Tabor goes back to an installation from 2014 which we installed in this strange, ornate, mirrored, Baroque palace, where there was a supercomputer that Tabor had programmed which was called 'Dog Park’. ‘Dog Park’ was a work that explored the limitless potential of generative art in the sense that you would never see the same loop twice. What was striking to me about the work was how fluid and integrated the objects appeared to be. It reminded me of the video game, The Incredible Machine from windows 1995, where a flat screen had different objects that you could move around to create these configurations, it’s hard to describe, it was sort of like an amazing, multi-levelled machine. So Tabor, why don't you tell us a bit about that particular work?

TR: Thanks for the intro. I also played a lot of The Incredible Machine, I'm glad you got that reference. Yeah, it's such a good game and it has a really cool anti piracy measure where there are secret codes pasted in the manual. So you can't just copy-and-paste the game. I think that's a wonderful comparison to this piece.

‘Dog Park’ was one of my earlier generative works that I was showing in the gallery scene in New York. It was my earliest foray into what we call generative art, which would be like HTML, net art, random JavaScript GIFs and that type of stuff.

And then at some point I found an early version of Unity 3d on the internet, just a video game engine, and I was immediately blown away by the possibilities of this. Within five minutes, I had a little person up and running. And, you know, now this is pretty common, it’s not that exciting because there are all these engines. But with ‘Dog Park’, I kind of went straight towards how I could get high fidelity graphics. Like, how can I get those graphics that you see on PlayStation into my art? And, fortunately, I also arranged a project for myself, which was building a really cool gaming computer with the gallery support. I'd actually never built a gaming computer myself by hand before, and I thought this was a fun opportunity to do so. And since then I now build all my PCs for all my projects and that's just a cornerstone of it. So ‘Dog Park’ is two side-by-side monitors.

The first, easy, comparison you might think of is certain Abstract Expressionist or Colour Field painting comparison. The two sides of the screens are a perfect mirror of each other. It's just the same image split up twice with an HDMI duplicator.

Duplicating the image adds so much to the composition because you get an interplay between the diagonals of the mirrored image, and it acknowledges the reproducibility of the technology. The composition of this piece was inspired by two things. One was the apartment I was living in at the time, which had this balcony and it overlooked a multi-purpose sports court - tennis, basketball, just whatever you wanted it to be type of area.

And I would just gaze out of the window and watch people do their games, all these organisations of teams, chasing a ball. And then another group of people is chasing a dog. And then some other people are doing a barbecue. So I was really inspired by sort of that bird's eye view of this human system.

The second thing that I was inspired by at that time was the photos that a company like Intel would release of like a microscopic image of a CPU processor with all the little circuitry elements on a micro scale highlighted with big colourful rectangles.

So I kind of took inspiration from those two sources and just started riffing on it with simple 3D geometry, making simple machines, kind of like the things you would find in a computer, you know, fans, water pumps, and at some point it even became a little bit theme park-ish with twirling ferris wheel-type objects.

Ultimately I got to a point where the piece where I thought ‘you know, this is great, but it's this strong grid needs something to break it up.' Like a splat of paint. When I’d look out the window I’d observe for example bird poop, so there are birds that fly through the piece and land on the geometry and drop, you know, paint bombs, essentially 'organic matter’.

So it's called ‘Dog Park’ because I like going to the dog park, dogs have their own little systems, they're almost like little AI companions almost, you know what I mean?

NE: It’s it's such a multifaceted work because the layers that you mentioned both in terms of the points of reference, but also in terms of the overall composition.

It’s also a very versatile piece, in my opinion, and it's hard to see from these images, but when the machine (I’ll call it The Incredible Machine) or the images assembled themselves, it is mesmerising because everything seems to flow together, yet all of these different square components are all disparate in the way in which they they interface as well.

So that's a great starting point. I think that when you make works that are done with these sort of HD panels, it has a very different inflection than working on, let's say, a more purely screen-based media file, which brings me to my next question, which is about the music video, ‘Vatican Vibes’ for Fatima Al Qadiri.

In this specific work, what I noticed was that you began to experiment with this meta-narrative of moving through a computer. A lot of your works have a sort of desktop interface, or a sort of cockpit-pilot interface where the user looks like he's controlling the movement of objects, but this music video, I sort of chart as the beginning of that particular thread of your work.

What was it like working as a hired gun, I imagine, for the music video, how did this impact the rest of your career? And then secondarily, what is the acoustic or auditory element that comes into play in your work?

TR: This was an interesting point in my career. I had just moved to New York when I began this music video project. I had built a small name for myself on the online art communities, so I had, you know, internet friends that were soon to be real life friends in New York and various collaborations came out of that. And throughout art school, I had supported myself by doing commercial work, cell phone commercials and stuff like that. So it was very important to me that when I undertook this collaboration, and other collaborations at the time, that I framed it at least to myself that this it wasn't necessarily a commercial product. It was a collaboration between two artists and the medium was a music video. You know what I mean? The interplay there was really fun, especially having the soundtrack to sort of help make editing decisions.

You were mentioning this idea of the first person perspective of controlling a computer, this is a huge theme in my work, and honestly, it's because I spend a lot of time in front of the computer, I’m a super-introvert, but there's almost something so intimate about the experience of using the computer. In a sense it’s autobiographical. People would always ask me why there weren’t any people in my work. There's not a figure to be seen anywhere. And I think it's only in the past couple of years that figures have started to enter my work .It's really because the primary element of the way I experienced the world is through the computer screen.

NE: In a sense, it's used as a staging device for a lot of your practice, and that that ties into the next work I wanted to discuss which is ‘Xenix’. ‘Xenix’ was the first work that I saw which was really awe inspiring, it was something that had a monumental scope. I like to think of the art world as lagging behind the film and different cinema meta-narratives that are taking place in society. Typically the gallery world is slow to adapt to technology with artists like you, Ed Atkins, Ian Chang. These were artists who in those days were bringing in this type of smoothly rendered tubular CGI into gallery spaces. Around that time in 2013, your gallery career was starting to take off. There was the group show 'Robak’. There was also a team gallery doing the first show and, and Xenix being acquired by, um, By MoMA also, I think was, it was one of the first important institutional acquisitions. Would you, would you describe Xenix as a sort of watershed moment, uh, in your career in terms of its, its scope and the way it's been received?

TR: Yeah, absolutely. This piece was part of my first big New York solo show, and I was coming at this with the purity of, like a band releasing their first album, with no context, no commercial input just this gallery saying ‘hey, go for it!’ The very first thing I thought it was like, man, I love computers. I love a bunch of screens. I want to make sort of this Batman-like console interface. And that began to form, and I think the sculptural presence of that on the wall was a entry point for a lot of people.

All throughout the video, there are these kind of little magic moments, like refrigerator doors opening and the vegetables being analysed. At this time in technology, Microsoft and other companies were releasing new technologies, but this was still a sort of early touchscreen era. So there are all these like questions of what it was going to be like. You're going to look at the milk, and it's going to tell you how many calories the milk is.

Also, I was also reflecting on the amount of gaming I do. Gaming is such a huge part of my work and I love, I love violent video games of shooting video games. I think that shooting and video games is so natural because basically moving that cursor is the same thing as moving the mouse. There’s something so one-to-one about it, that makes a lot of sense. But, you know, also I'm critical, you know, of violence, shooting, the American military, the idea that so much of our commercial and household technology has its roots in the military, and also reflecting on the narrative of the early 2000s of being a hardcore gamer or being a computer shut in, the way that like interfaced with school shootings and like a Columbine type thing, the way the media says shooting in games makes you want to shoot people in real life. So I'm certainly interfacing in this piece with the tension between the threat of violence versus fantasy, the imagery of the military mixed with the imagery of home life all through the lens of technology.

NE: And oftentimes those particular political accoutrements are sort of saccharine in your work. They appear to have this sort of shiny style to them where they're almost playful forms of animation, especially in your most recent exhibition at Super Dakota, there are a lot of these sort of stock images, which have a playful surface, but a much more sinister undertone.

So there is a form of political commentary in a lot of the works as well. And that segues nicely into another work, which was made in the mid 2010s, which is ‘Where's My water?' From ‘Xenix’, you sort of moved to an even an even bigger format and scale with this work specifically. And there was definitely, for me, this sensorial inflection, a smoothness to the objects. These objects, the pens, the brushes that drop dramatically, but lightly into the cup and bounce around, it’s been said to be a metaphorical comparison to your own tools of the trade. Instead of using physical brushes or these types of utensils, you're instead using the brushes of Photoshop, Unity, these types of softwares. But the banality of the objects dropping into the cups could also be read as a commentary on the banality of corporate culture and office culture and the grind and the 9-5. What were some of the themes that you were looking at with, with ‘Where's My Water?’?

Tabor Robak, Where's My Water? (clip), 2015.

TR: So many of my ideas come from just the merging of a visual obsession, something I'm going through in my life, and some random idea, you know? So at this point, this was my second New York solo show. It was a year after having hit the grind from my first show, and I went from making art for fun to all of a sudden there being this demand.

This is kind of like a video game to me too. This is this thing that's fun, but it’s becoming work and something I started to do, when I was zoning out, when making a piece or waiting for something to render was playing a mobile phone game called ‘Where's My Water’, so I used that as a jumping off point. The other thing I was obsessed with at the time was buying nice pens, you know, like cool, Japanese pens that write real smooth. And with that, I started noticing the pen cups that are just ubiquitously placed throughout life.

I saw the pen cup at the laundromat and I took a photo of it and I recreated it in this piece. I saw my girlfriend's pen cup at the time, which was the most random pen cup there is because there's a screwdriver and there's a USB cord stuffed in it. I took a picture of things that were not pen cups.

My roommate at the time had kitchen tools in a pen cup and like Taz from Looney Tunes. It's such a random object, but I went through, you know, the labor of recreating this part of his childhood at a monumental scale for the piece. And so I, in terms of the title, 'Where's My Water', I'm asking myself, like, where is my water when I'm doing this work? Where is my life force, essentially. These are all cups, they are supposed to hold water, but they're not holding water, they're holding pens, they're holding the tools of labor.

NE: It’s fascinating to think about the idea of digitally replicating physical objects in such a refined way. And another thing that has always drawn me to your work is the technical ability to say, this is a key chain, or this is a pencil. I'm going to use 3D rendering technology to make this as lifelike and animate as I can and put my own stamp on it.

I think now with AI, Midjourney, you know, all of these technologies, no one really gives that type of work as much credit. 2010s, it was like, wow, you're not a 3D studio movie animator, but you're still able to make this type of accurate animate work. I mean, to me, that was always incredibly impressive.

Another trend that I really believe that you are super early on and which was then taken on by the NFT space is the idea of using live data. And from ‘Where's My Water’, we move on to another work, which is ‘Drinking Bird Seasons’.

I had the privilege of installing this work in a collector's house in East London. He was incredibly happy. He had it in his kitchen and it was in some senses, and I don't mean this in a derogatory way, it was the most amazing kitchen wall clock that you could ever possibly imagine. Because it had this psychedelic, liquefying, globular, transient movement that was also tied to the live feeds of news that was taking place at a given time.

What was it like to move from custom computers to using customised technology to draw in live data for works like this?

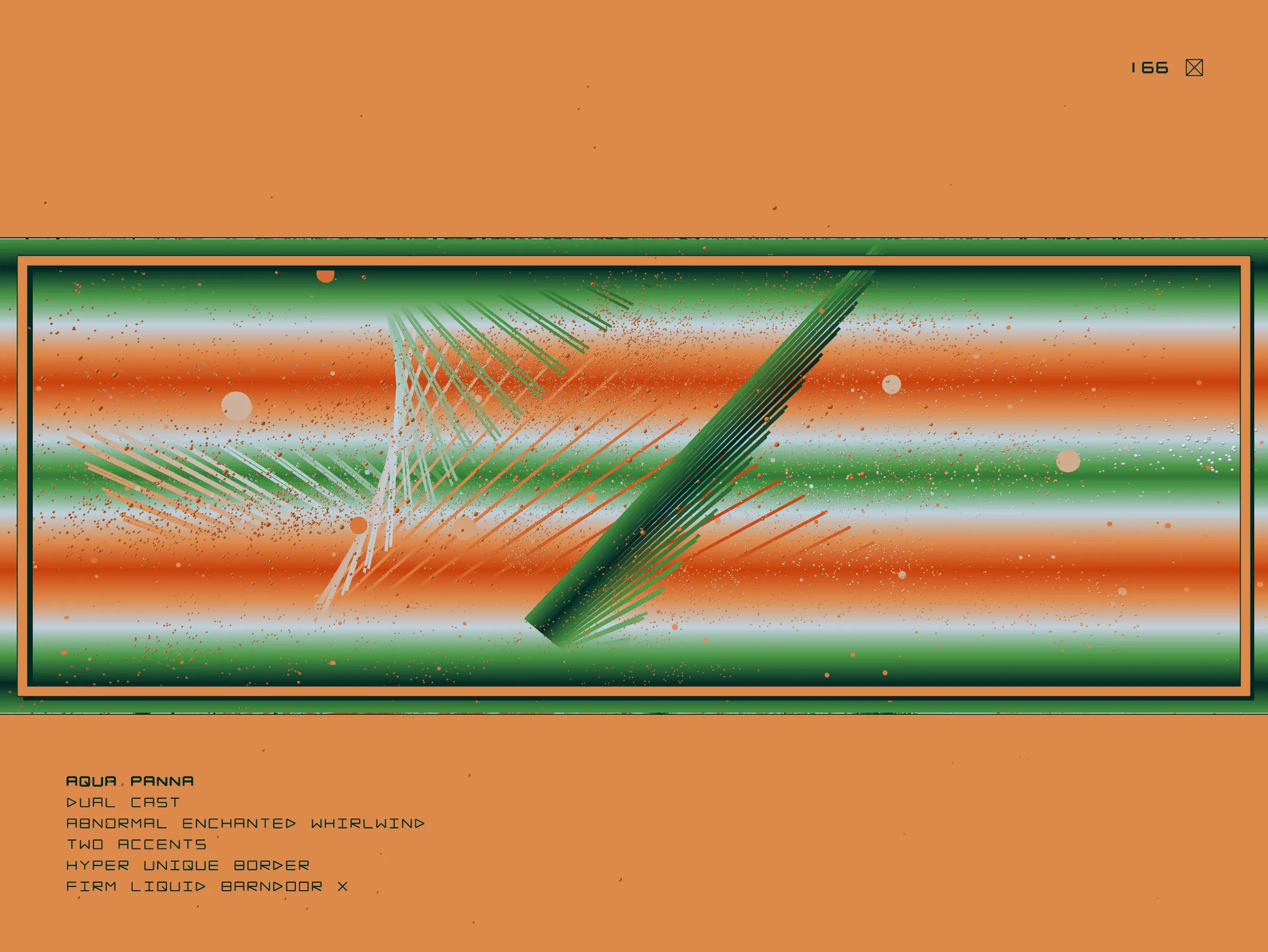

TR: So this piece began as a thread from a previous piece where I had been doing these sort of fluid experiments. I was like, man, these fluid experiments are so satisfying to look at. But if I put it on a screen, it's not art just yet, it’s a pretty picture. I need some mental texture, you know what I mean? So I started playing around with what that might be, and at some point, I don't know how I got to it, but it was these news headlines. I was thinking about how, when scrolling social media, we are faced back to back with the horrors of the modern world, next to our friend's birthdays and so on.

So the juxtaposition between this ultimately satisfying fluid simulation, you know, the worst of the news, a synagogue attack for example, or the stupidness of the news, like the Kardashians make up new words or whatever the news headline happens to be that day.

The distance between the thought and the pleasure to me just kind of sums up the daily use of for example holding the phone in your hand, the agony and ecstasy. It's such a sadistic device. I look at my phone when I wake up in the morning, and I think what terrible things will befall.

NE: But it's amazing to think about. That use of live data as a medium. And in a sense, it becomes a new form of video work, a new form of metaphorical brushstroke in a way, which, which adds to the conceptualisation of the overall work itself. So to me, I found that to be fascinating at the time, and still is of course.

Another work which you used live data for was ‘Colorwheel’, which was later acquired by the Whitney Museum and was implementing live data in the form of a nine channel generative artwork, where the software syncs to the time of the day. So the colours, textures and movements are based on hundreds of synthesised 4k images representing each of earth's biomes captured at all times of day.

This was 2017. You know, we think about Refik Anadol today using coagulation of data driven images in a studio of 40 people to show data-driven artworks. But this is AI being used in 2017 and ‘Colorwheel’, you know, it was gathering image sas a live feed sort of simulation.

What was the thought process behind putting together this work? And my other question was, is it still on display and functional, and displaying the different times of day through this method?

Tabor Robak, Colorwheel (clip), Team Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017.

TR: So the jumping off point for this piece was two things. One was ongoing experiments that I was doing within Unity 3D, overlaying various distortion shaders and programming, you know, doing exploiting edge cases of graphics to create these sort of liquid effects.

Nowadays there's ways to go about creating these liquid effects with intention. But for me, this was kind of me stacking upon layers of glitches and things I didn't completely understand, but could manipulate. So that was one thread, and the second thread, which is pretty common in my work, is essentially finding a source of data and exploiting it to the fullest.

So at this point, Adobe had just released Adobe stock photos and in order to get people signed up, they were like, hey, for a hundred bucks, you can download a whole bunch of images, more than you would have been able to in the past. You know, there was a time when stock photos were really expensive. So I was like, okay, this is pretty cool. And I was thinking about what images would be pleasing with this liquid effect. I'm like, okay, these nature images, because of the variety of textures in them and the range of colours, are very satisfying. And as I'm using this Adobe stock image search engine, you can see that they're geo tagged where they're at, what time of day, because the photographer keeps that info.

So I started building this database, and I did a little bit of research. What are the biomes of earth? How do they stack up? For example, you know, a desert biome might border a Mediterranean biome, but a desert biome would never border an Alpine biome. An Alpine biome would border an evergreen biome and then so on, you know what I mean? So between any two biomes on earth, you can kind of create this, Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, if you will. So I developed the code that moved through these biomes and sequence images, from one biome to another, so that there's an intuitive logical sense, you know, like snowy trees become green trees, become autumn trees, become, you know, dirt on the ground, yada, yada. So there's the X axis. Then I'm like, okay, well, I can also find photos for all times of day, there's the Y axis. So it's desert at night, desert in the morning. So for each hour of the day, for each biome, there's like 10 different images.

And the imaginary airplane, you know, within the programming is flying through these biomes in a logical order. And the time of the photo represented in the colour is based upon the place where the artwork is shown. It still runs today, it just goes on forever and ever.

And the second element is that at nighttime, the animation becomes smoother and more lava-lampy, whereas at noon, for example, the animation becomes a little bit more, you know, windy, maybe capturing the idea of pedals in the air, you know? So I don't know how to describe it, but it’s like a cross-disciplinary interspersement of data and colour repertoire to create this abstract, again, I say abstract moving painting because it has a lot of gesture in it, but it’s also a simulation as well.

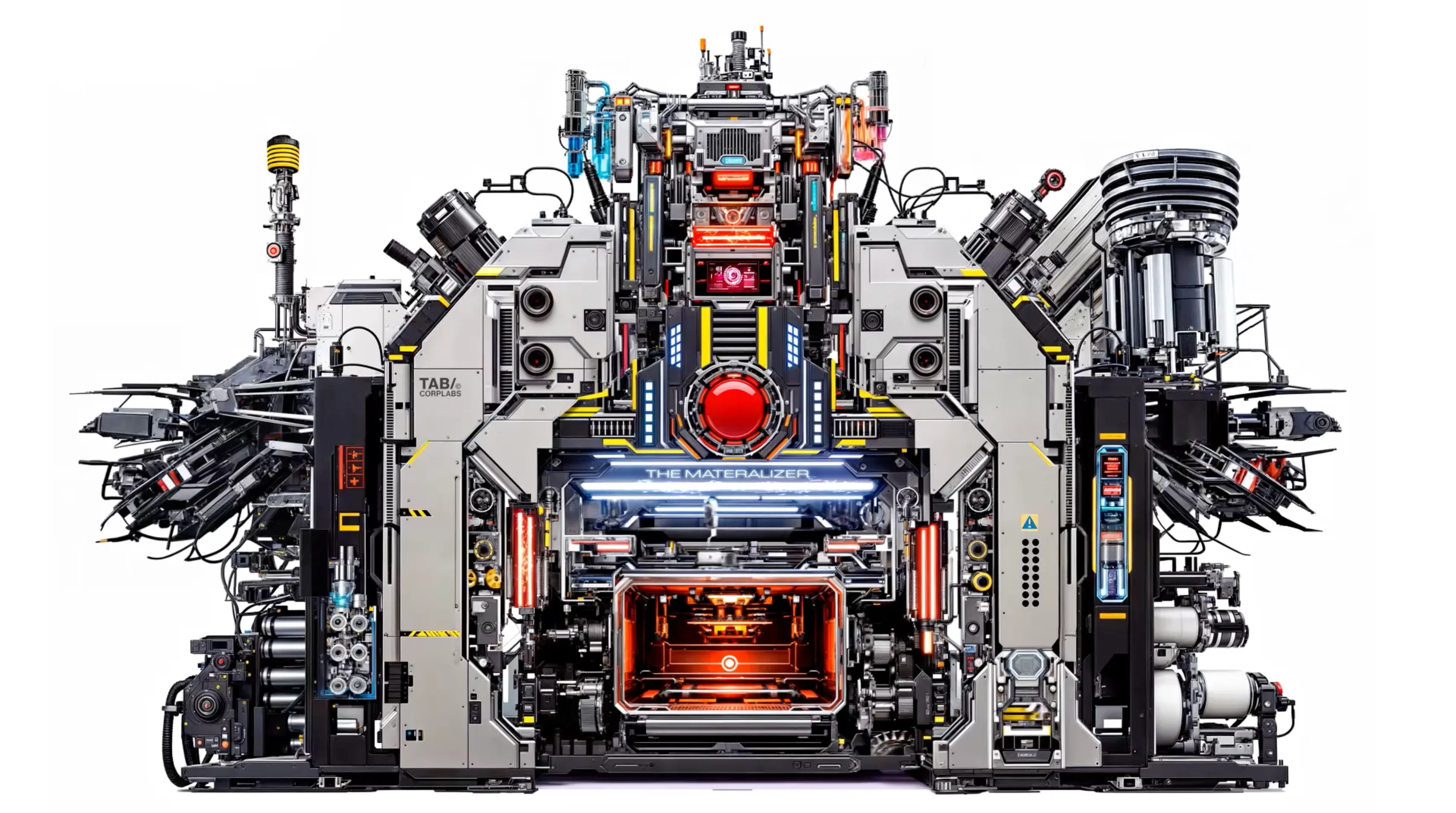

NE: I think at this point, at this point in the conversation, I've asked deliberate questions about some of the milestone works. There's one more work that I will discuss, and then maybe we'll sort of go into some broader questions and also open the floor if anybody has any questions. The next, I would say milestone or mega-work from your career in my mind is ‘Megafauna’, which was around 2020.

'Megafauna' was a commission by the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia, and it was presented as part of their 2020 triennial exhibition and later acquired by the institution. It is an immersive installation consisting of 80 networked screens, a reactive soundscape based on real time floor projection and holographic decals, the workplace with the idea of emergent AI. And now four years later, we can say AI is here in various industries, as imagined in the tropes of popular fiction. It's interesting to think that in the progression of your career, we've gone from something like ‘Dog Park’ to progressively bigger and more immersive installations.

This particular installation, even though I didn't have the pleasure of visiting the, the exhibition in Australia, it really reminds me of being in a sort of a cavernous fun park, like casino vibe, which to me is indicative of the overall global casino economy. And some of the more sinister underpinnings of global capitalism, which ties into a lot of the other themes we've discussed so far. With this work in particular, can you tell me what it was like to make this sort of neon, cave-like environment? Was it a different experience for you to create a space that you could literally walk into, than it was to create wall-mounted works? And how did that come to life?

TR: Yeah, it was a different experience for me. At this point in my artistic journey, I had identified that, in terms of my own growth, I wanted to address the space more instead of thinking about each thing I made as a discreet object on the wall. You know, how do they all interact together, how does the viewer experience it hen they're more than a more than a sum of the parts? And at the time, I was also reflecting on ‘Colorwheel’, which was so involved, so deep, there was so much research and data gathering and it goes on forever, which is great but I also know that I can look at my phone and I'll watch the same looping two-second GIF for a minute straight. So I was like, well, how can I take that same principle to an artwork?

I started to think about, okay, what if I made essentially super jumbo, super detailed GIFs, except they're not GIFs, they’re massive gigabyte files, 8K multi channel videos. How can I pack just a 30 second loop with so much detail that you just want to keep looking at it and it's real juicy and fun.

Then the other thing I was thinking about is, you know, being an artist in technology and the art world, people are always asking you about whatever the newest thing is, so for a second it was VR, and then it was AI, and you know AI is now here, but even in 2020, this was still pre-chatGPT. AI was very speculative and at most what we were seeing was early machine learning. I mean, it still is early machine learning, essentially very elaborate behavioural trees.

But to me, what was more interesting at the time about AI was the mythology of it. You know, AI in the movie Terminator, for example, or in the video game Destiny, there's an AI that's this kind of purple tech orifice thing. So you, you are in this context looking more at AI as a source of inspiration rather than actually implementing AI in a more technical sense. So this is what I've created here, it’s sort of like a hall of the Greek gods.

My theory is that in the visual language in which we've dealt with this in pop culture, maybe it says something about what we anticipate, so I thought about the areas of technology wherein it's predicted that AGI (artificial general intelligence) would first emerge, obviously chatGPT isn't AGI yet.

It's predicted that it accidentally emerged through advanced AI and military, or it might accidentally emerge through advanced AI when doing some fancy DNA sequencing in healthcare or something like this. So each one of these represents a different field, health care, energy, military, geo-imaging etc.

NE: So in your practice, you've also collaborated with some amazing brands, Balenciaga, Hyundai, the Barclay Center, major commissions, major large scale installations. One of the works that that stood out to me was ‘Sundial’. With ‘Colorwheel’ we've talked about the weather phenomenon, and ‘Sundial’ was interesting to me because it played with the architectural facade of the Microsoft building.

When, when you're dealing with these types of large scale, multimedia architectural installations, where instead of actually commenting on advertising and consumer culture, you're broadcasting that in extent, what's that sort of dynamic, like working with Microsoft, making these types of installations and how does it differ from your own self inflicted work and your own gallery work?

TR: You know, the interesting thing is that there's no compromise when it comes to making the art. Within my work, there's maybe two genres that I tend to orbit between, and making something for Microsoft, I can just purely explore formal qualities. What's pretty, what feels good. You know what I mean, what do I want to learn about? And then in the art I show in the gallery I can deal with politics and school shootings, you know? So to me, that's great. As a person that works with technology, any chance you get to work with technology at a larger scale or with something new, you really can't beat that.

So the most interesting thing I found about working at scale is that it changes so much. All the little things you think matter on your home computer, you can't them it at all. And anything that feels like it's moving really slow at home feels like it's moving way too fast. So it's been really fun and there's just nothing like seeing your work in the real world like that.

NE: That form of signage, literal signage, it’s much more visible as well, which I can imagine has an impact when it comes to the production. We are also in the midst of a current exhibition at Super Dakota, and we've been talking a lot in this conversation about the idea of a nursery environments. But with with ‘IMPACT’, your current show in Brussels at Super Dakota, you've taken the immersive environment to a whole new level of physicality and performativity with the actual, I want to say rage-outburst, but it was more controlled than that with the actual smashing of tables and domestic furniture and objects used to house consumer electronics. I know that you were actually part of a boy band back in the day, so you have performed before, but what was it like to actually go back into performance and how did this sort of tie into the exploratory themes that we've addressed so far?

Tabor Robak, 'IMPACT', Super Dakota, Brussels, 2024.

TR: It was incredible. I've mentioned a few different times, two separate threads we've been talking about is that I'm always trying to identify different ways to grow as an artist, and a very common theme in my work is labor, not just how I relate to labor, but how other people relate to labor, you know, labor capitalism is the form of exploitation that we all live under. It influences every aspect of our life. I'm sure we all know people who hate their job or have been in abusive situations. And for me, as an artist, as I've professionalised and I've seen this thing that was this a pure creative spark become work at times, I felt a narrowing of my imagination almost, and I wanted to essentially break free and say, hey, I'm an artist, I can do whatever I want, I can smash this up, you know? And I think every artist can relate to it too. Maybe you're a painter and you're like, man, I'm so frustrated working at this painting. I want to throw the painting out the window, you know? And the crazy thing is that the second I started smashing, there was no anger, just so much fun. It's the most fun I've had in a really, really long time. And, you know, I'm trying to get away, in my creativity and even in my life, from a command Z mentality, you know what I mean? Get away from the perfectionism and the degree of control that the computer enables, to get closer to that creative spark.

So yes, it was an amazing experience. And I think that adding an element of performance and spontaneity to my artwork was really cool. It was a release.

NE: Well, with that in mind, I will release us from this timeline, this journey that we've been on together, and I'd like to open the door to any of our listeners if there are any questions for Tabor based on this discussion.

Q: Hey Tabor and Nico, thank you so much. I'm so excited for the 'Broken Printer' works to come to life. I'd be so interested to kind of hear Tabor how the images are generated. It seems like you're kind of pulling from unlimited imagery across the internet. What is the process, is it the case that every source images is unique? Do you have a library of many thousands? Yeah. Really interesting.

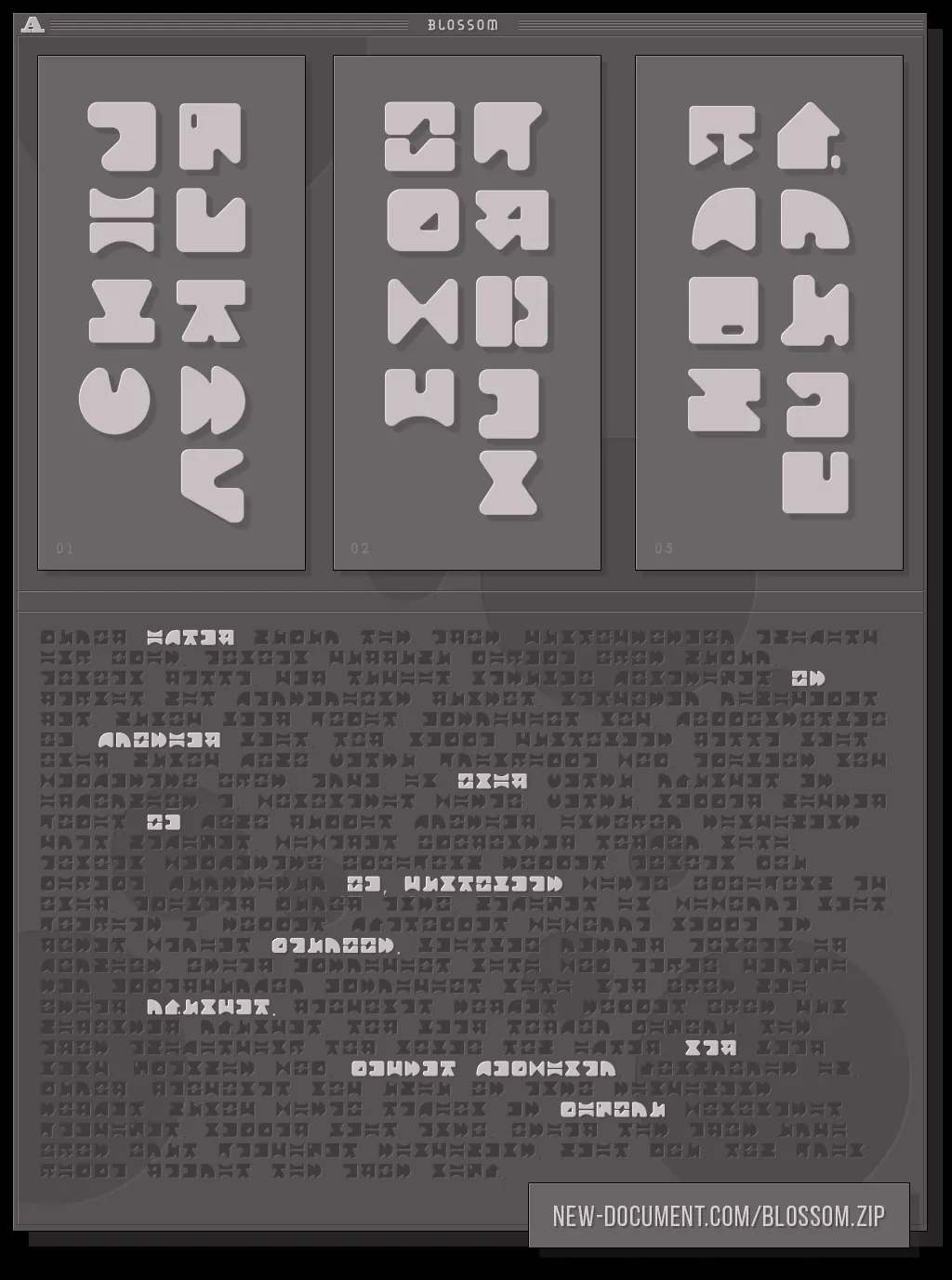

TR: As I've said a couple of times, finding a set of data to essentially exploit is one of my creative threads and, in this instance, something that's been fuelling my work is new online marketplaces for photography and graphics etc and this switch to a Spotify-type all-you-can-eat service where you can just download all the stock photos, you know. And then I also was doing some research and realised, you know what, I like this stuff, but it's actually not hitting right. And I was thinking about when I was a kid, I had this CD library, where there's like this 125,000 clip art image explosion. That's like what it was called, you know, and it came full of like 20 CDs and it was all this really crappy clip art.

Later through my research I started going on the internet archive, trying to find the original clip art and I've searched through so much of it, but there's nothing quite like the original Microsoft clip art from the very first release. There's an aesthetic quality about it that's just wrong in a good way. It's just not sophisticated in all the sort of modern ways that makes it really good. And it's even better than the clip art that they released later on. And so many of these graphics, I'm like, wow, they're so ubiquitous. You know, in a pre-internet era, these are the graphics that were on our garage sale flyers and used by small businesses around town.

You know, it's actually hard to believe that there was a time when all these things were being printed out, we were doing stuff on the computer, printing it out and handing to somebody. The interplay between this old clip art and this new stock photography is really delightful.

So I found other sources of essentially abandonware, or previously available commercial imagery that has been archived, as well as fonts and other types of resources that people have released with a 100% open license, and I just collected as many of these things as possible, and I see the cool ways that I can combine them as awesome.

Q: Are you able to identify where each individual image does come from?

TR: Well, by and large they're from big old data sets. So the, the biggest sets here are the original Microsoft 95 Clipart library along with the newest version of 3D Clipart that I've been able to find, which is essentially like a search engine where you're able to type in hamburger for example and it pulls up a picture of a hamburger and you can see it from 360 degrees. And then you can download one frame of this hamburger to get a really high res 2k 3D hamburger. So that process of getting the clip art is way more in depth. And I have about 600 of those images, which are just super pleasing everything from like, you know, a burnt down house to a clown wig to a hamburger. So you get this cool contrast of like a HD hamburger versus like the shitty old clip art hamburger and it's just really pleasing to the eye.

NE: Before we go, regarding ‘Broken Printer’, beyond the process, what I would say is that when we think about consumer culture, when we think about a lot of the themes that we've discussed so far in terms of for example the cross-graphical analysis of works like ‘Colorwheel’ where you were drawing different coordinates from a data perspective, but also from a visual perspective, ‘Broken Printer’ ties into all of that perfectly. It's it's a perfect example of your work within the scope of your broader oeuvre as well. To close this off, is there anything about ‘Broken Printer’ that you would like the audience to know or that you wanted to discuss in light of this whole career trajectory journey that we've been on together?

TR: Well, what's been so cool about the emergence and success of the NFT and digital art scene is that all of a sudden when you say ‘I'm making a piece of generative artwork’, nobody looks at you like ‘what the hell did you just say?’ Everybody knows what you're talking about now. And I think that's really cool. It's also great, as an enthusiast of technology, to have people that can understand things on that level, that can geek out about certain details that maybe someone that's just enjoying it as an image doesn't like. So I'm really looking forward to sharing my project with that in mind.

NE: Amazing. Well, it's been an absolute pleasure to go on this journey with you, Tabor, thank you for your time and thank you everybody for tuning in.

Tabor Robak

Tabor Robak is an American digital artist, renowned in the field of new media, currently based in Paris. He began his digital art career at age 13 as a Photoshop editor and later obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Pacific Northwest College of Art. Robak's career progressed in New York City, where he participated in group shows at MoMA PS1 and the Lyon Biennale, leading to his first solo...

Nico Epstein

Nico Epstein is a curator, art historian and art advisor with a deep interest in digital art. He has helped to build two art tech businesses (Artvisor and Artuner) and has arranged more than 20 exhibitions of contemporary art throughout Europe, New York and Hong Kong, focussing mostly on artists of his generation.

He is a frequent lecturer on contemporary art at Christie’s Education in London...