Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

'Think the image, don't make it.' Frieder Nake in conversation with Mark Webster and Julien Gachadoat

Frieder Nake, Mark Webster, and Julien Gachadoat in conversation with Mimi Nguyen.

Mark Webster: I’ve been teaching this project for a couple of years now, called the Recode project and yesterday my students did some presentations - they presented five or six artists and their artworks. We discussed a little bit about their choice, about why they find the work interesting and how they could do this in code. One of my students chose Julien Gachadoat, who is with us here today!

Mimi Nguyen: How I first learned about Frieder, was when I gave students an essay topic on the future of digital art. Many of them started by explaining the beginnings of digital art, and they recalled, for example, Frieder Nake. I thought Oh my God, I need to meet this Nake guy.

Frieder Nake: You can return to them and tell them that you have seen him, however, only as a picture. So, you don't really know whether he exists. Now, maybe that is a fantastic program, that picture that looks as if it could, perhaps be a human being. Nowadays much younger students are doing these things and when they come across people like me, they're saying How was it possible? Have there been computers in the 1960s? Already? Isn't that something new that we had in our pockets all the time?”

Mark Webster: When I present this project, I share in a little bit of history. I’ve shown them this wonderful German documentary with an overview of Frieder’s work, I think it was on German television in the 1960s. It was with this old ZUSE machine with plugs, and all these flashing lights. You know, it's fascinating for the students to realise that a computer back in those days took up a whole room, a huge space, and there were lots of different people involved in the process.

Frieder Nake: That is really amazing when you think that we are talking about a time span of roughly sixty years only. Now, what happened concerning this type of machinery during those sixty years? Of course, from the point of view of somebody, who is now between 30 or 40, sixty years is a lot. But from the point of view of the whole history of technology, sixty years is almost nothing!

Mimi Nguyen: Even forty years is crazy! Julien, you, started coding when you were 8.

Julien Gachadoat: I was lucky enough to have a computer at home because my father was a teacher. He brought back a very old computer, with 4kb RAM. I was playing video games, but I was also compelled to do coding and so started coding without knowing what it meant at the time. I have been doing this for years now. Forty years now, referring to when you were talking about the flashing lights and all that big machinery. I discovered those old computers and have followed their evolution, as you said, to this point where we can now put a computer in our pocket – that’s quite amazing how fast this has evolved.

Frieder Nake: If you add to this, that the power of the central unit, the amount of storage, in this small little thing you have in your pocket, is more than many of those old computers, it is quite beyond me. I don't believe I can really understand what has happened there. In terms of technology, it seems impossible. This is why it is justified to call this kind of machine postmodern, because the postmodern machinery was heavy, and loud, and stinking, and everything. And now all that is gone. It's even ridiculous to think of a smartphone as a machine. An umbrella is much larger.

Mimi Nguyen: Mark, when did you start your journey with coding? How did you get into machines?

Mark Webster: Like Julien, I had a computer as well, when I was very young. It was 48k Spectrum and I used to code a little bit in BASIC – it was the language of the 1980s. We hated BASIC. Well, I hated it. But I didn't start working with languages like Processing or Java until a lot later in 2005.

That was due to a wonderful meeting that I had with John Maeda. It was John Maeda, who talked to me about Processing, about Casey Reas and Ben Fry. He also talked a lot about creative coding all the while presenting to me this amazing exhibition at La Fondation Cartier in Paris – the only one he did in Europe. He was showing me all these works, and he was talking about the code. For me, who only knew BASIC, coding was mainly for programming games. I hadn’t made the link with creating artwork with code. That particular meeting with John was very, very special to me. It was there, that I began to discover the potential of programming for art.

Frieder Nake: I'm gonna leave you now, I horribly envy you for having met Maeda in person. I never met him, nor have I ever met Casey Reas, or Ben Fry. John had himself created that little language he called DBN Design By Numbers. And then Casey and Ben, still as students, decided: “okay, that's not good enough.” And that's the origin of Processing! They designed Processing, in some sense as a continuum along with what Maeda had started. Fantastic! I mean, that story is already 20 years old now, but when I first spoke to Casey, I told him: Look, this is fantastic, I'll use Processing!

I came back to Bremen, and when the semester started, I told my colleagues: I will not teach, as you do, Java. Because Java is a crime for first-semester students.

They were flabbergasted: What are you doing?

But it was a success. Processing gets students immediately. You sit down and you write the first program, which is two lines, and the program is empty and doing nothing, but it's already a correct program. And then you say: should we perhaps make the program do something? You're about to print a famous line ‘hello, world’. You put that line there, and it runs, and it prints. Fantastic! Now, as you add more and more, and you say: okay, now let's do art. Everybody starts doing his or her art. They can sit there forever, and I can go home.

Mark Webster: You raised an interesting point here. For someone who was coding in the 1960s, you didn't have an interface with the computer. You didn't have a program like Processing. You were writing your program by hand.

Frieder Nake: It’s really different, and a little sentimental to talk about this. But it's also great if you had the chance, as I did, to live through the time when you were sitting at your desk, no computer around, just nothing. The computer is not far away, but it is away because it needs very low temperature and humidity. Therefore, we were sitting in this air-conditioned computer room. When you go there, you get the machine for one hour. You had to announce this a week before. You now are sitting in your room writing by hand the program and you try to be as efficient as possible, efficient in the sense of not committing any errors.

I’ll show you something. In preparation for my afternoon classes, I found this book - it is the first book on computer art and at the same time a PhD thesis, sponsored by Siemens. Defended in 1969. It's the first in the world PhD thesis, which topic is computer graphics, in the sense of aesthetics. I had this book with a dedication by Georg Nees, and one student stole it from me. I don't even know who it was. And then I got sent this new copy with a letter from a guy from the publishing house, saying he's proud of giving me his book.

Okay, so I wanted to show you this: here is a piece of code, you don't have to read and understand it at all. It looks different from what we would do now. It's, for instance, absolutely unnecessary, that there are these lines, and they must be numbered. You know, ridiculous for us nowadays. Totally ridiculous. And the commands there, you cannot understand them. Unless you know, this type of programming language. It's impossible. It's a mixture between Algol and a lower-level language used in German universities. You were not allowed to use Fortran. We always used Algol - that was European. Fortran - American. Look, these are images that he produced. This is full of those. And then you think, this is a doctorate in philosophy, not in engineering or anything!

Mimi Nguyen: Mark referred to the sentence you once said: Think the image, don't make it. What did you mean by that?

Frieder Nake: Think the image, don't make it... I wanted to characterise something by this short line that one can remember. I wanted to clearly characterise what we are doing, when some gallery puts up your pictures, thereby a gallery and the curators acknowledging that this could be considered perhaps as something artistic. We don't make the images. For that, we have the machine. We think the images – which sounds impossible! There are these metaphors: (I imagine an image) with closed eyes, or you could also say with eyes wide shut. Not like the traditional artists who draw with their eyes wide open, like Paul Klee - always watching everything, seeing, and seeing quite differently. The traditional artist absorbs everything that he can possibly watch, and then through his inner process, he paints. But our thinking comes from inside and then projects the image onto paper or canvas or whatever it may be. Better if it's even moving. Think the image, don't make it.

Mark Webster: Do you refer to the artist with this statement?

Frieder Nake: Yes.

Mark Webster: Because you could also refer to the spectator.

Frieder Nake: The spectator's role is more difficult. Let’s take the spectator, the audience in general: they come to the gallery, they come to the museum, they are not interested in anything. They come to the museum only because it's raining outside, they would otherwise never enter, and so forth. It's horrible. So they enter this room. It's really empty and vastly large. And there are paintings on the walls. I know those paintings quite well because I do go to museums, even if the sun is shining outside. They are all sad these paintings, they are crying. I visit them in order to tell them I would like to touch them. Stroke them a bit. But the lines hanging around them don't allow me to do this. They have no idea I feel the sad paintings. Because nobody is really admiring them. They only come and they look: Ah, Van Gogh, okay. And they pass on to the next one: Picasso, oh! They don't study these. They don't get into the image.

Mark Webster: Well, that's an interesting point. Frieder. Without the spectator, art doesn't exist in a certain dimension. So, you need the spectator for the art to become art.

Frieder Nake: Absolutely. There are museums that are in financial trouble nowadays, that are in this country funded to a large extent by the state from cultural budgets. But in the current situation, I bet, in the ministries, you already have people drawing up plans which museum should be closed. Now they will have statistics and so forth. They are horrible guys. They will soon change the landscape of art, I'm afraid.

Mimi Nguyen: A lot of museums are now digitising their physical works and trying to sell them as digital versions to make money. Speaking of physical works, Julian, I remember when I spoke to you first on Instagram, I didn't even know that you were doing NFTs when I was inquiring about your physical posters. And then I learned that you joined the NFT space quite early, you had an ArtBlocks drop last year. What drew you to NFTs?

Julien Gachadoat: I was curious about that space. When you have a lot of friends doing this, and it was the case last year, I was just curious about the platforms, and how one could possibly do generative art online. With the ability for the collector, to not see what he is going to buy. For ArtBlocks, I thought it was quite incredible at the time, and I still think it is. And I believe that the success of platforms like ArtBlocks in general, is that people are very interested in this process.

Those platforms have allowed generative art to get to a wider audience and to make people understand what we are doing. I always get asked how I make these images. I often tell people that I don't draw anything, I just code, adding some process and ideas, and I'm not sure about the results I will get😊 Nowadays more people are discovering this process of making images with programming languages and code that is going through a machine. It’s fascinating, and what Frieder said, we use the machine to produce images, but what is very relevant today, is that it can also be diffused across the world. Generative art is still a little world, but now with the blockchain and NFTs, it can be spread further. I was curious, first as an artist, but then also with the fact that you can easily collect art too.

Mimi Nguyen: Mark, you, Julien, and Frieder met for a seminar in France in 2014?

Mark Webster: Back in 2013. I had the honour of organising along with Julien, a lecture and workshop Frieder. He delivered a brilliant lecture that traces his experience of the arrival of the computer in the art world, recounting a passionate story of the first-ever exhibition to present algorithmic artwork. Entitled Computer-Grafik, the exhibition took place in February 1965 in Stuttgart and presented work by Georg Nees.

Mimi Nguyen: And what about the future of generative art?

Frieder Nake: It's a challenging question, extremely challenging. I am a person who has learned and I believe, who is totally living in the present. Not in the past, nor in the future. And that's beautiful. I celebrate each and every day. You always believe the future is what you do, that the image from the computer will grow in quantity. Now, we are already surrounded by digital algorithmic computer images, without often noticing, and this will even become more present. We will be bombarded by images, which at the same time will mean that images become trivial. And this bombardment will change our way of thinking. In my case, it is definitely true. My thinking has been constructed by reading books, which I still love. My thinking is a book-kind of thinking. And when you ask what do I think the future will bring? There will be new artists, maybe artists even younger than you - they will come up with ideas that an old brain like mine is just not capable of having the faintest idea of. The visual revolution has been already declared several times by people, but it has not really happened yet, I believe. Well, my students don't read books anymore. There are always a few, but the majority are not reading books anymore. They are staring at screens. Staring at screens is the new dimension that has pushed aside the reading of books. Both rely on our eyes. You need eyes in order to read a book, you need eyes in order to stare at a screen. Actually, that's a negative term. I should not use it. They are enjoying looking at a screen. Enjoying looking at the screen.

Mark Webster: I'm surprised that you are a little bit negative about this Frieder. But I understand it as well because we're already in this situation, where we consume images. It's no longer what we're seeing, we're no longer looking, but we're consuming just as we consume everything else. It's kind of like throwaway culture, which is terrible. There are however possibilities to bring us back to a more contemplative state of looking again. And we need this even more so with what is happening at the moment with NFT's, where projects are coming and going week in week out. These are images that appear and disappear from the collective memory. They're not even memorised anymore. It raises questions about the role of a gallery or a museum or places that are there to not just necessarily archive work but to present it in the first place. And to give it the light that it requires. Because, again, images and art only exist through the spectator, and therefore the people coming in and looking, not consuming, but looking. I think the role of the gallery, as you know, is very, very important in that. I hate to think that, you know, galleries and museums are going to disappear. They may take on other forms, but also, I tend to believe that we also need to change as well. It's a question of slowing down and being able to take the time and space to be in the present. As you say, quite rightly, but also accept that the things that we have accumulated and learned are part of our collective personal memory, that we project on everything that we see. So as opposed to just letting images come and go, it would be nice to see that people can stop and think the image.

Mimi Nguyen: Can you share more about the new project Hypertype?

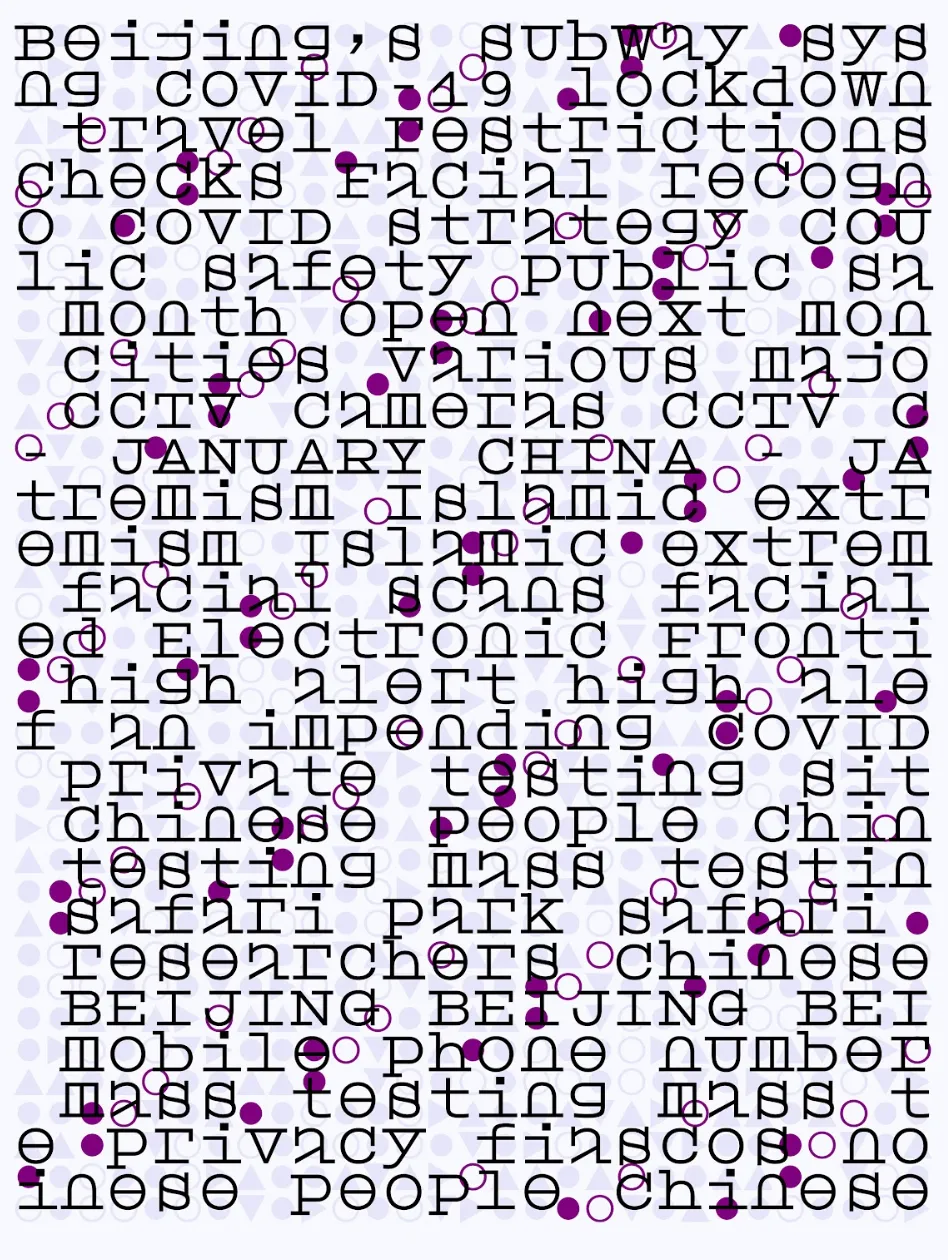

Mark Webster: Hypertype is a generative work that uses text sentiment analysis data as its main content. You know, text sentiment analysis is an increasingly used technology that attempts to derive emotional content from written text. Like facial emotion detection, it relies on a classical view of how emotions work in which there is a common belief in universal emotions that are somehow innate in our behaviour and expression. In order to explore this idea, I've chosen a variety of news articles, research papers and presentations on the subjects of emotion, facial recognition and affective computing and analysed them using IBM's NLP Sentiment API. This raw data is then used as content for creating unique generative pieces that play with text and typographic form.

Hypertype is first and foremost a textual work that relies on the visual interaction of a variety of typographic signs and letters. There is visual content based on a language system and there is visual context based on a subject matter - computers automating humans.

What I am trying to achieve is a means for transformation of one media that is manipulative of one’s attention in order to instil dogma, to another that is manipulative of one’s attention in order to encourage introspection.

Frieder Nake: I share a lot with what you say here and indicate you say take time, enjoy a slowdown. You know, the current time of a hyper-capitalism will come to an end, whether the end will be horrible, namely, an enormous war, or with atomic bombs, and so forth. These values: slowing down, enjoying yourself and living. And that also means reducing. I may have told you that I have throughout my life, considered the salary of a university professor as corruption. The state corrupts us by giving us huge salaries. They may be not huge, but they are large, they are too much. And therefore, long ago in my life, I started to give away for many years 30% of the money, and nowadays 50%. I have enough and everybody should have about that amount of money that I have. But more - I do not need. Also setting limits, that's what you should do. Even when I’ll cycle to the university later, I will tell the students let's set a limit.

Mark Webster: When you say you cycle, Frieder, you're talking about a pedal bike or electric bike?

Frieder Nake: No, no, no, not electric. Occasionally you fall. I have a thing here, when the bone came out that time a car hit me. I got up, and cycled to the university. I was a little late because of that. The students sitting there were staring at me. Frieder, what is wrong? The car hit you, you’re full of blood! I didn't notice this because I did not have a mirror. That must have been a fantastic moment for the students. When the teacher comes in covered in blood. A vampire?

FOREWORD

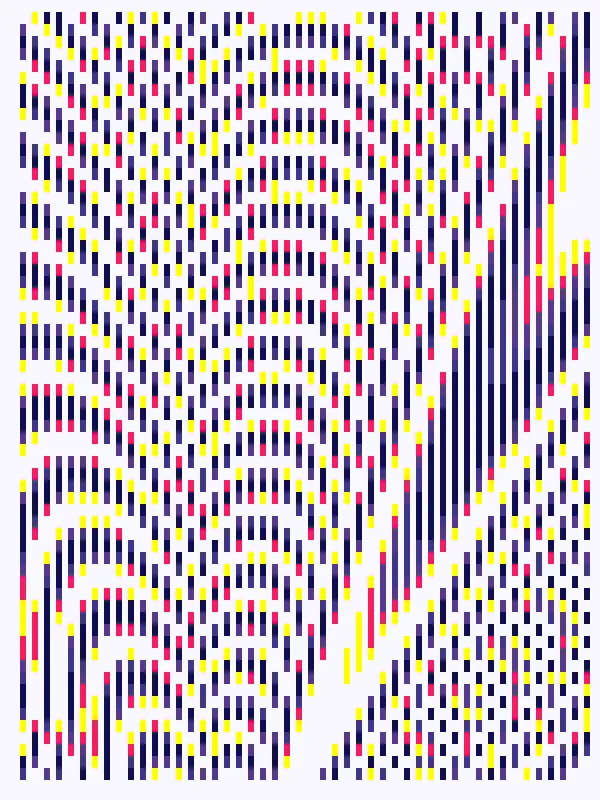

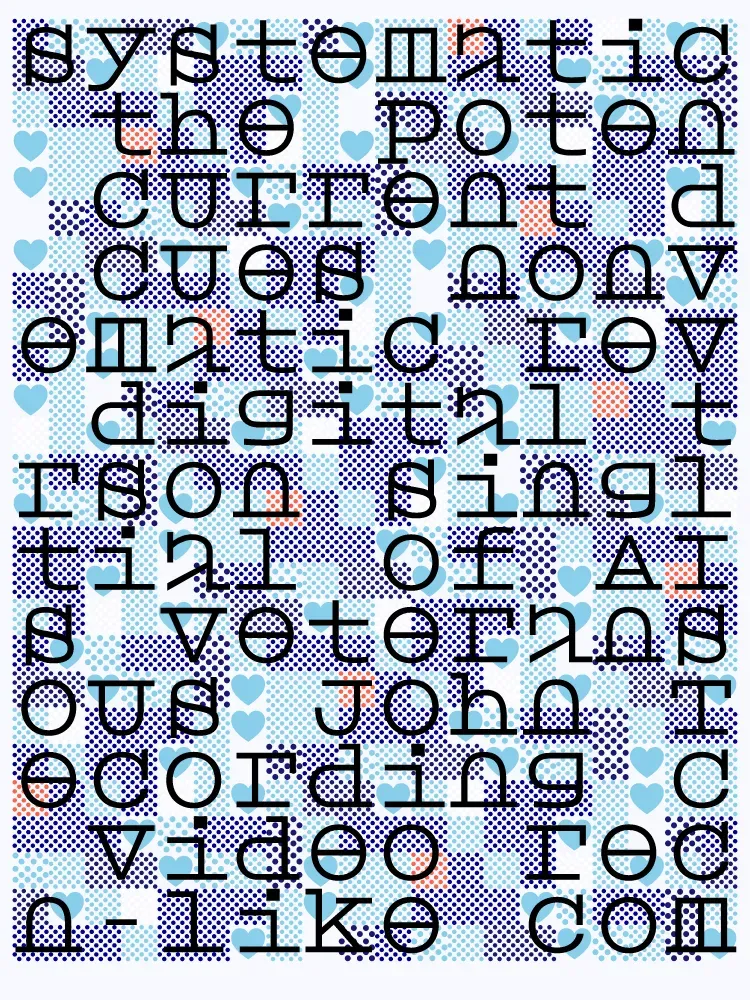

Andreas Gysin: Hypertype is made up of layers of text from whole phrases to single characters and typographic symbols, creating patterns through repetition and spatial displacement. Two main layers offset with varying glyph sizes creating visually interesting overlaps. While one of the layers remains either black or white, the other features a small palette of colours.

The font used for Hypertype has been designed specifically for the project and looks strangely futuristic with familiar letters becoming quite abstract in form. Some letters are completely closed like the ‘u’, ‘e’ and ‘v’ while others have common parts missing - the most remarkable example being the open bowl of the lowercase ‘a’. Such ambiguity in the letter construction may well reveal part of the project’s intention. Clarity, readability and even understanding may well not be a priority of the project but due to how our brains are wired and the fact that English words can still be deciphered, we grasp at meaning from these abstract forms.

The context of an underlying program that is trained to analyse and classify sentiment and emotion is mirrored back to us in a sort of convoluted feedback loop, from man to machine and back.

As I’m looking through some of the infinite variations generated from Hypertype, one in particular strikes me. It features a heart, a plus sign and some letters. It reminds me of a declaration of love like the one one may see etched into a tree or a stone. Two initials brought together under one sign, anonymous to most passersby but charged with meaning and sentiment for those these little symbols represent.

Frieder Nake is a mathematician, computer scientist, and pioneer of computer art. He belongs to the founding fathers of (digital) computer art, and produced his first works in 1963. Nake is best known internationally for his contributions to the earliest manifestations of computer art, a field of computing that made its first public appearances with three small exhibitions in 1960s. He first exhibited his drawings at Galerie Wendelin Niedlichin Stuttgart in November 1965. Nake has been a full professor of computer science at the University of Bremen, Germany, since 1972. Since 2005, he has also been teaching at the University of the Arts, Bremen. His teaching and research activities are in computer graphics, digital media, computer art, design of interactive systems, computational semiotics, and general theory of computing.

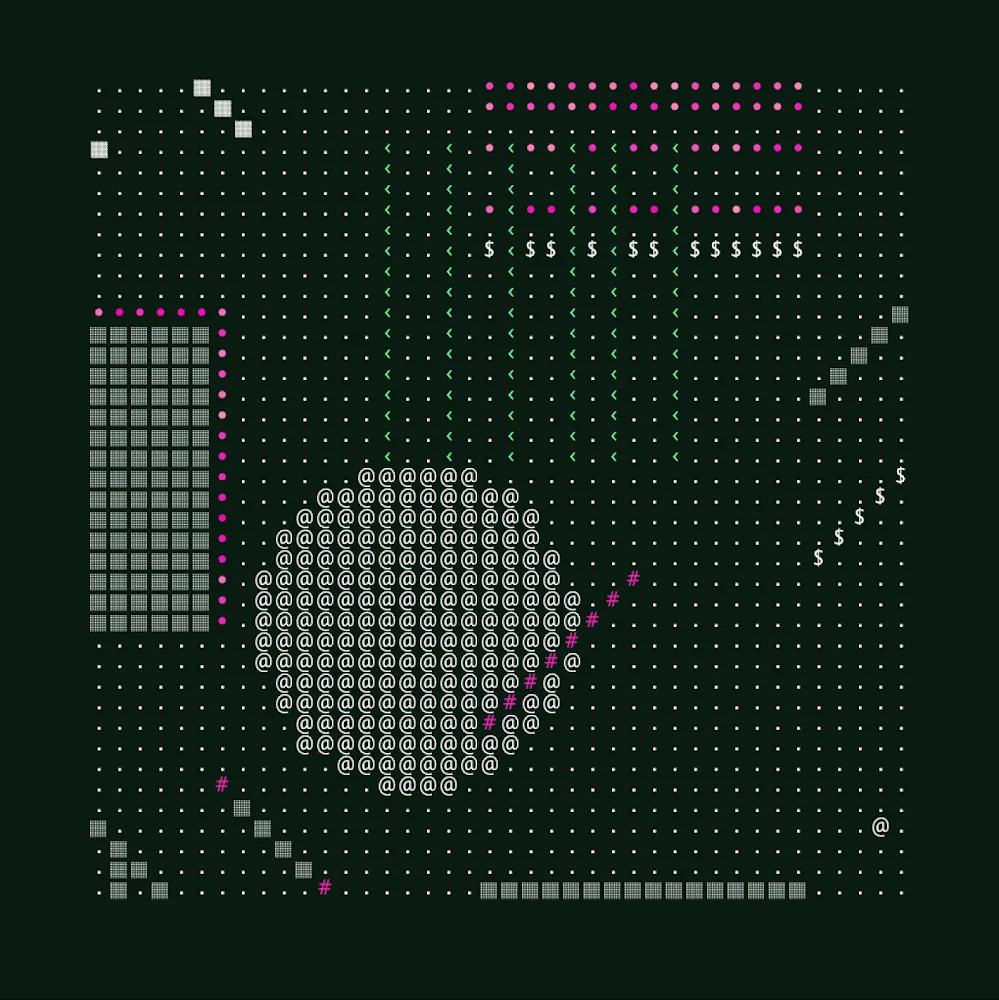

Julien Gachadoat has been exploring generative drawing for many years, creating unique art with algorithms. He works with the emergence of abstract form, combining monochrome, geometric shapes, playing with repetition, and using random operations to generate an element of surprise. Developing his own tools of creation based on simple graphic rules, Julien Gachadoat uses the computer—“this unique performer” —to explore the formal possibilities that ensue. It is through the process of printing these unique pieces, using a plotter (axidraw), that he creates a link between text and code. He brings together, on paper, the computer and the pencil, the rigour of code and the poetry of art. Julien grew up in the ’90s with the demo-scene, making visuals with code. Ever since then, programming languages have been his creative tools.

Mark Webster's work involves an eclectic mix of activities in diverse areas such as animation, sound design, graphic design, teaching and even a stint as a journalist working in the field of motion design. In the last couple of years, his efforts have been devoted to developing a body of personal artistic work that is driven by curiosity to explore and experiment with code based media. He creates art and graphic work primarily using custom-made software tools along with computational and generative strategies as his main approach.

Andreas Gysin is an artist, designer, and coder. Research, experimentation, analysis, and discovery are the fundaments of the creative process for his both artistic and commercial projects. Based in Lugano, Switzerland. Works often in duo with Sidi Vanetti.

Mimi Nguyen, Creative Director at verse.works. She is a doctoral researcher and teaches at Imperial College London, Faculty of Engineering, where she leads Mana Lab, a “Future of work in Blockchain” research group, and at Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London together with CSM NFT Lab. Her previous research on creativity and human-computer interaction has been published by Cambridge University Press, Design Studies, Design Research Society, TIME magazine, and ACM Association for Computing Machinery.

Andreas Gysin wrote the foreword for Mark Webster for Verse's exhibition 'Hypertype' showcasing his new long-form generative art series, with ArtBlocks Engine.

See the works on the 8th November at 6:00pm BST | 1:00pm EST.

Mimi Nguyen

Mimi is a Creative Director at verse. She is a assistant professor at Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London where she leads the CSM NFT Lab. Her background is New Media Art, having previously studied at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) and Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. She now also teaches at Imperial College London, Faculty of Engineering, where she leads Mana Lab - a “Future...

Mark Webster

Mark Webster was born in Canada, raised in England and currently lives in France. After graduating in London with a modern languages degree in 1997, he moved to Paris and began to orientate his work towards the arts. This has involved an eclectic mix of activities in diverse areas such as animation, sound design, graphic design, teaching and even a stint as a journalist working in the field of...

Julien Gachadoat

Julien Gachadoat (a.k.a v3ga) has been exploring generative drawing for many years, creating unique art with algorithms. He works with the emergence of abstract form, combining monochrome, geometric shapes, playing with repetition, and using random operations to generate an element of surprise.

Developing his own tools of creation based on simple graphic rules, Julien Gachadoat uses the computer...