Tactile Studies of the Synthetic Landscape

“There is no longer either man or nature, only the process that produces the one within the other and couples the machines.” — Deleuze & Guattari, Anti-Oedipus.

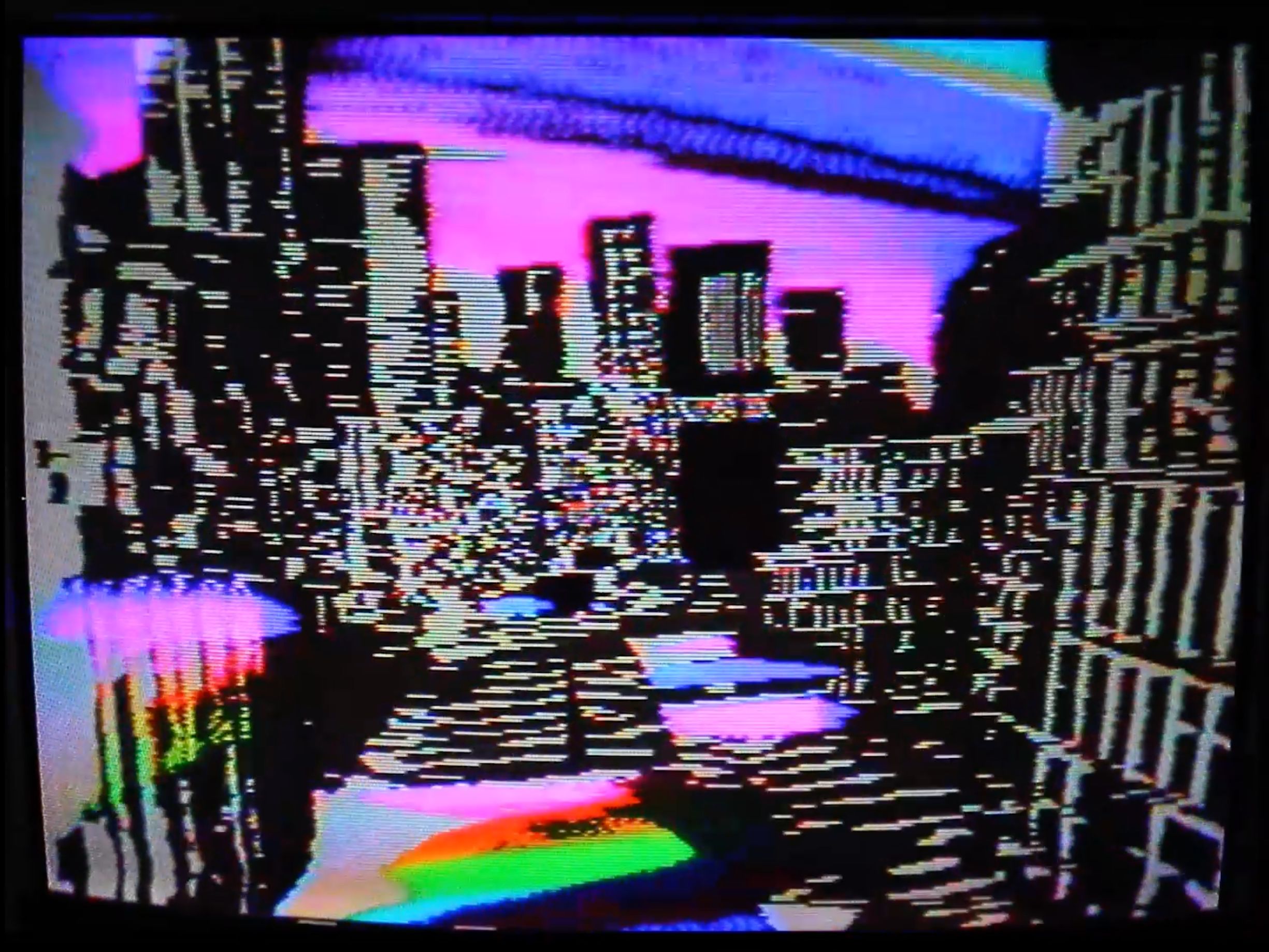

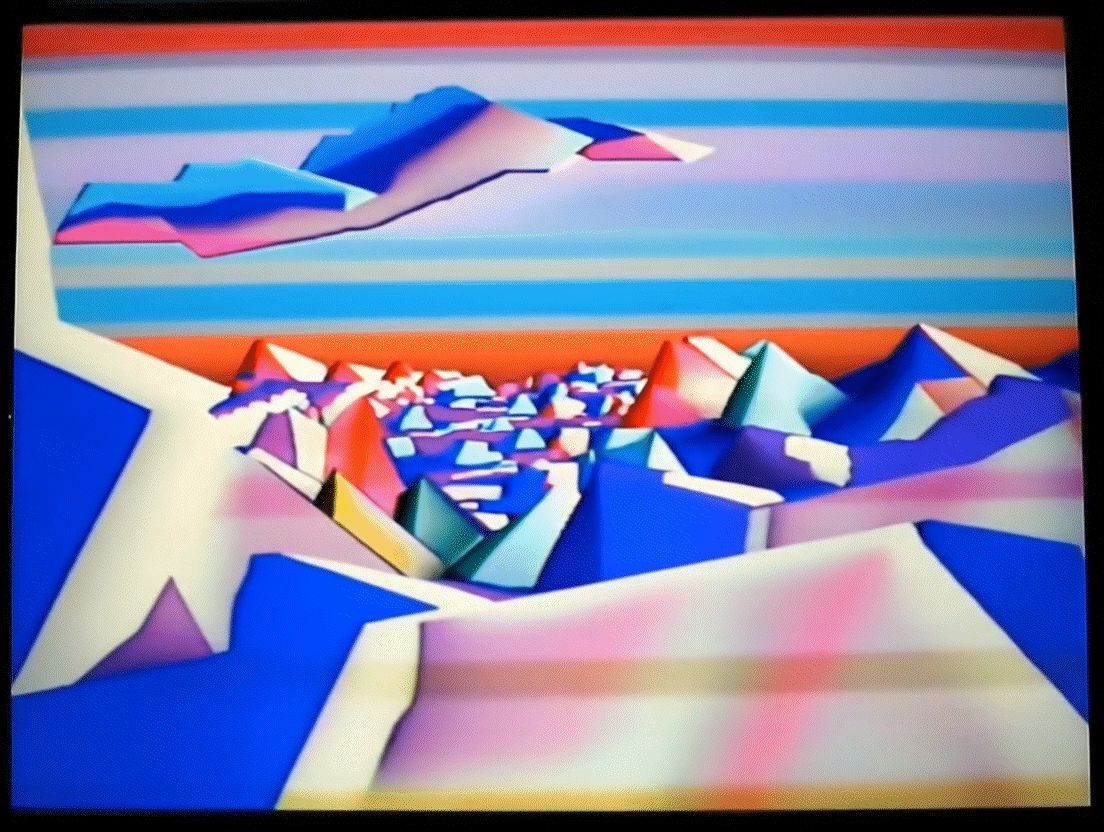

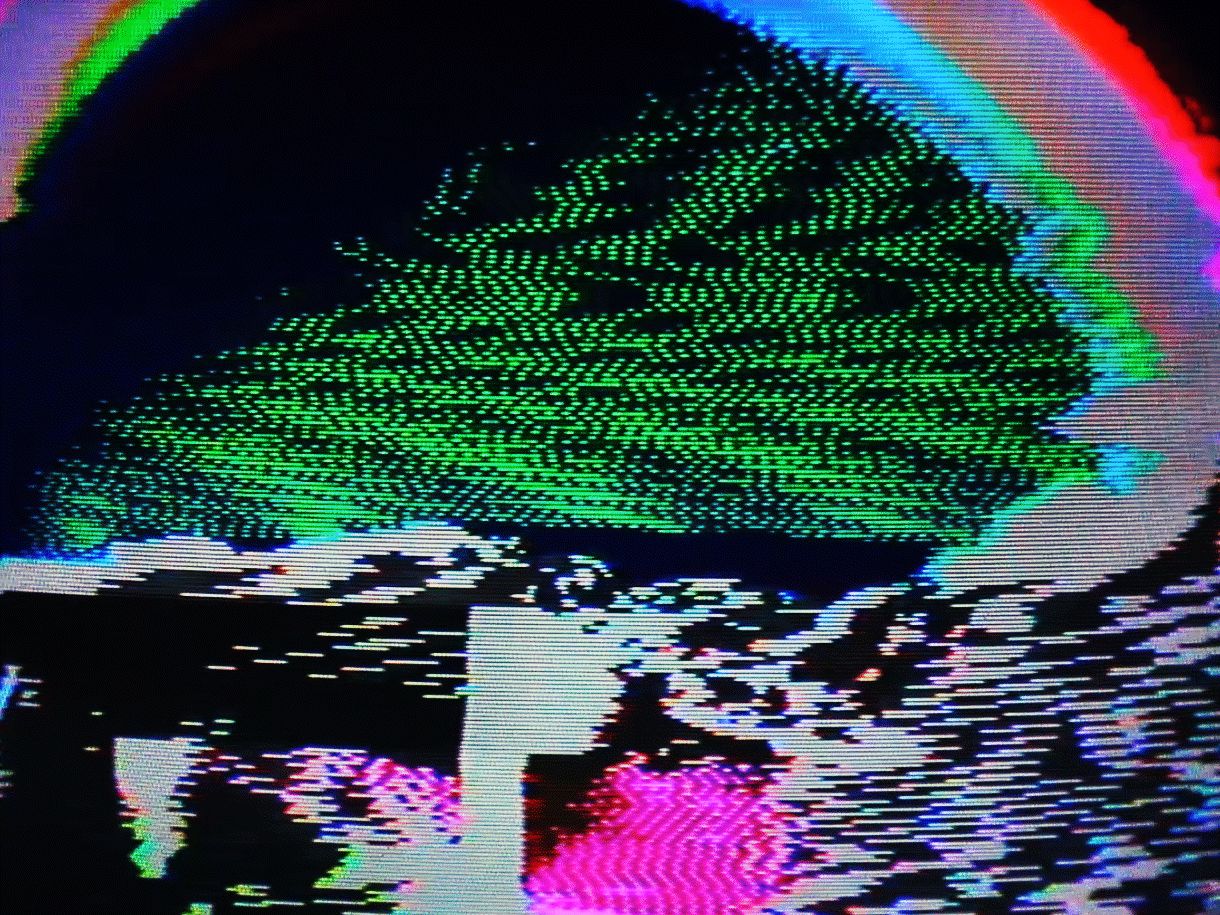

We begin this collaboration with a deliberate muddle: what would happen if the computer longed to step on grass? That contemporary daydream of leaving everything behind to live in another time, another air, another course. What would happen if the computer could think itself into that other place as we do? What would it imagine? Where would the machine escape to reconnect with nature? We think that, in its desire to touch grass, what would be most proper to it is to dream landscapes.

The computer has become our way of mediating life: not only because it rules our personal and private communications beyond immediate proximity, but because almost all the time it is mediating and remediating our desires. Yet this machine, which is completely intertwined with our desires, cannot desire. There we place a large part of our question: how can we make landscapes with machines that are proper to the machine? How can we imagine computers desiring a landscape?

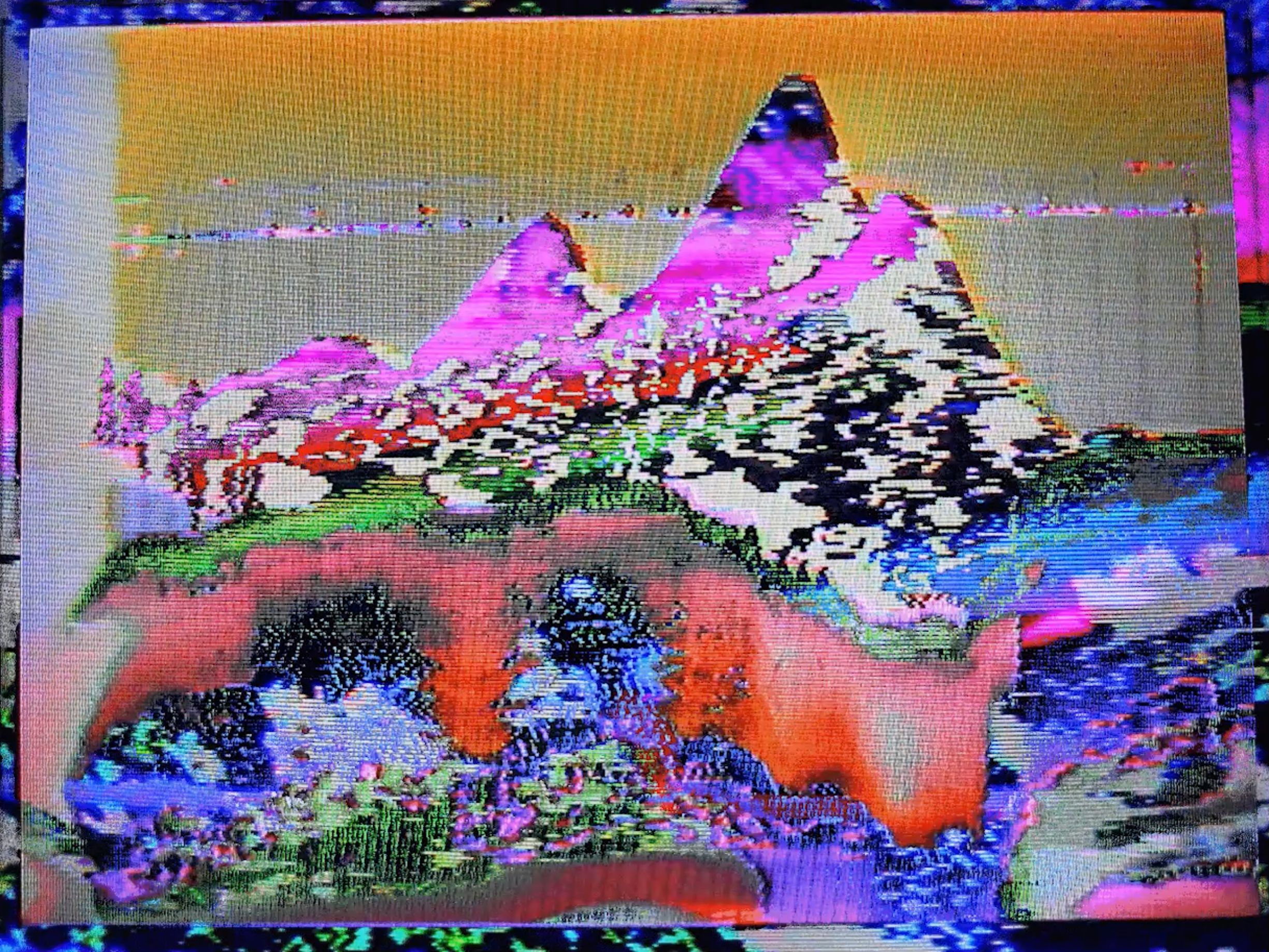

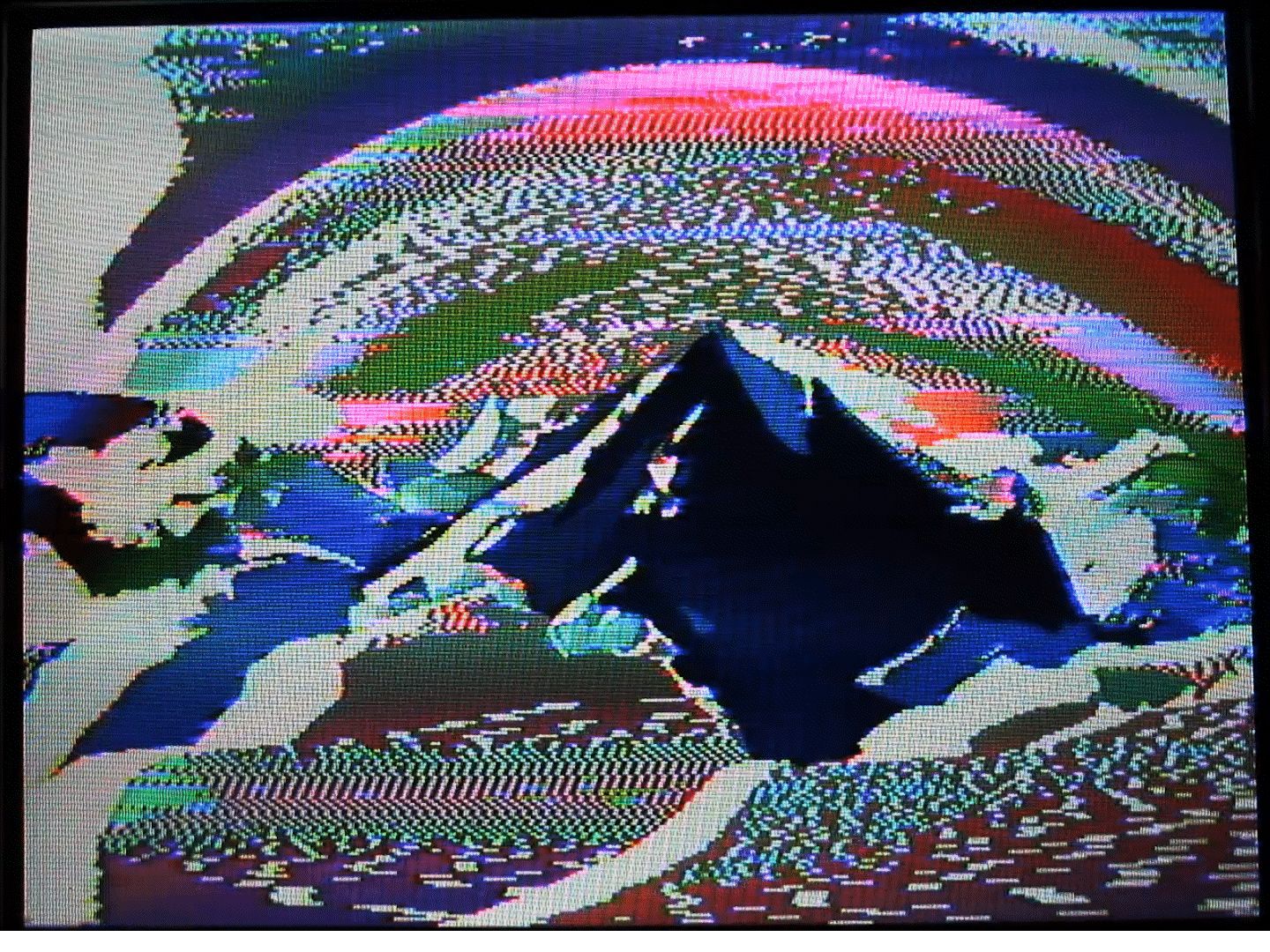

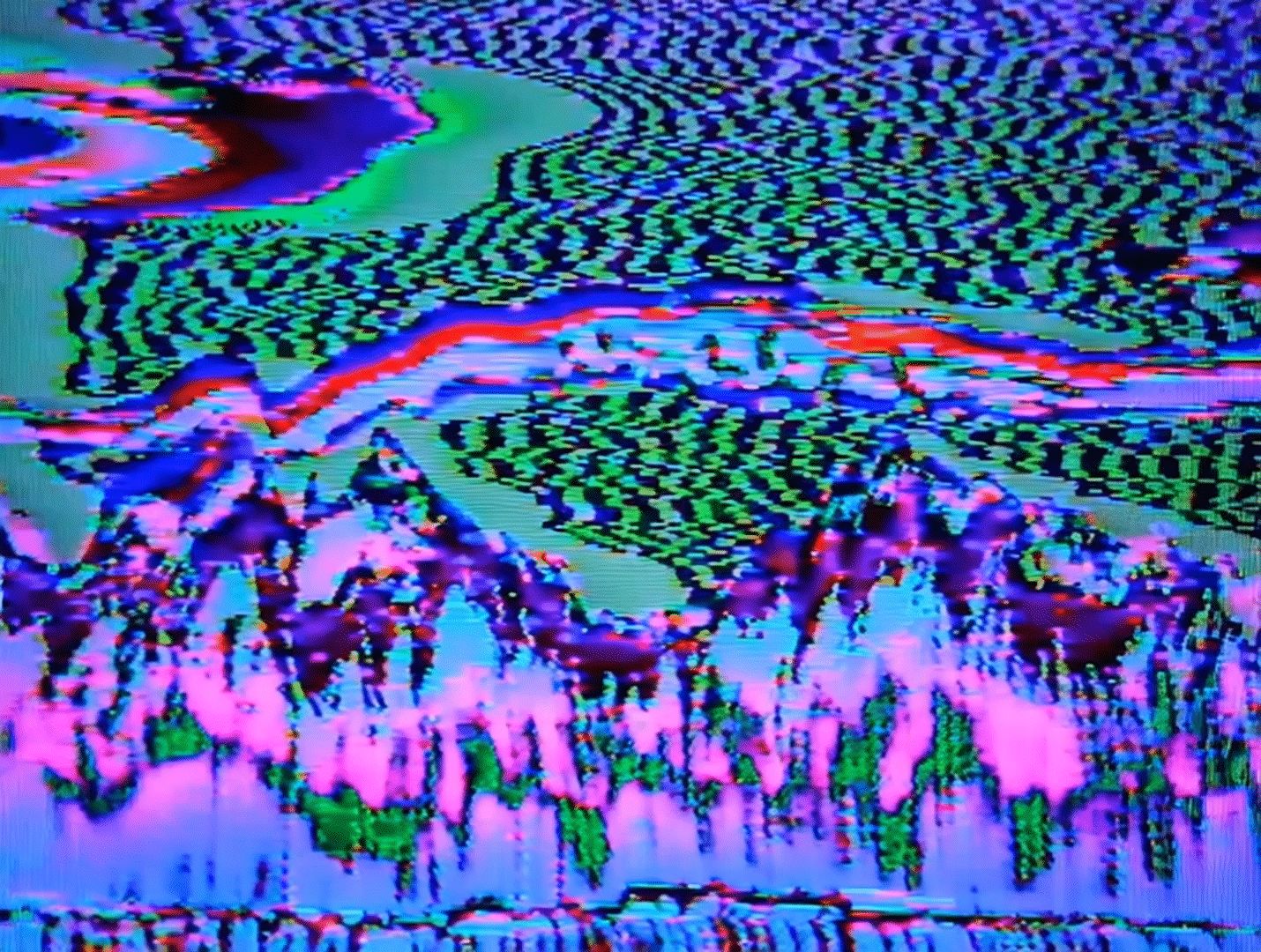

All of this, as we said, is a muddle, but there is something there: we live in a time in which we have moved from simulacrum and simulation via the computer to a phase of generation, where computers can pour into the world ideas, forms, and all manner of media content. We are also here to sift those contents, as their own algorithm might; but unlike LLMs, we are drawn to moments when the work strays from the obvious and leans into the strange—when we can truly observe the computer in a generative mode rather than merely a representational one.

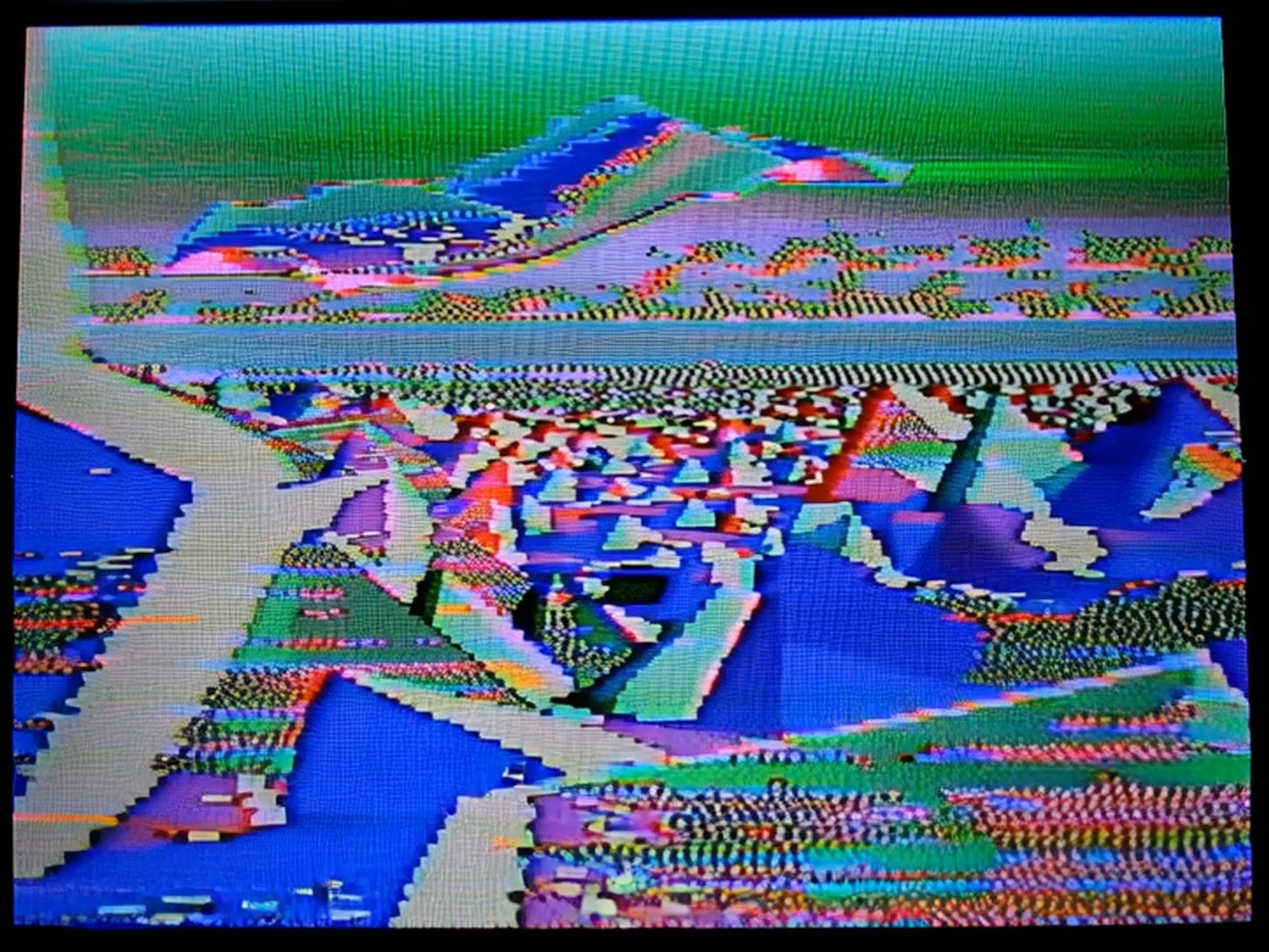

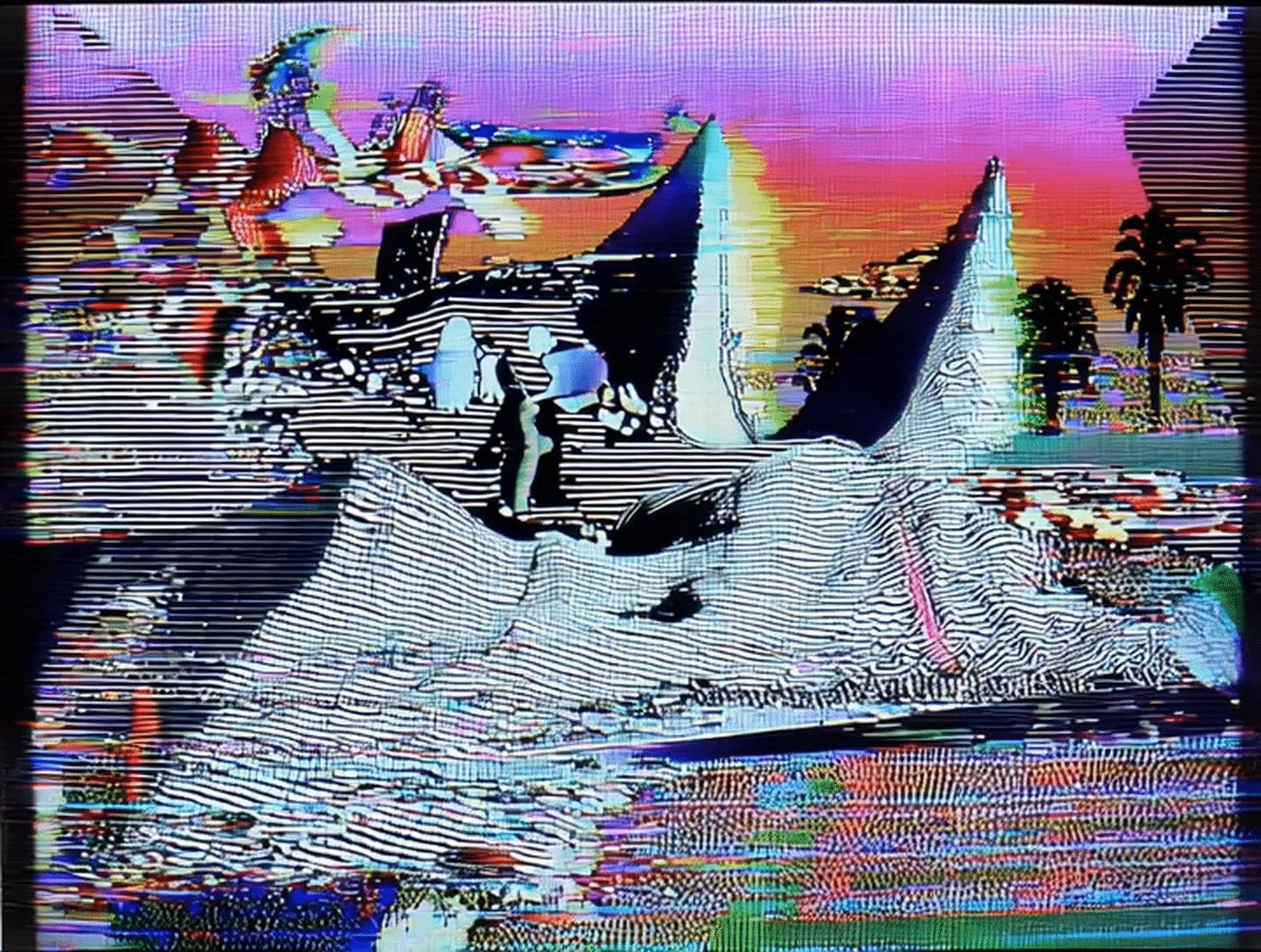

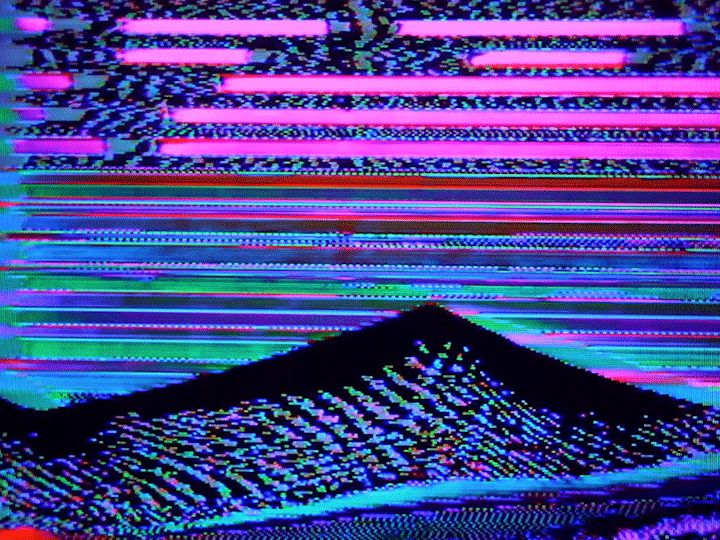

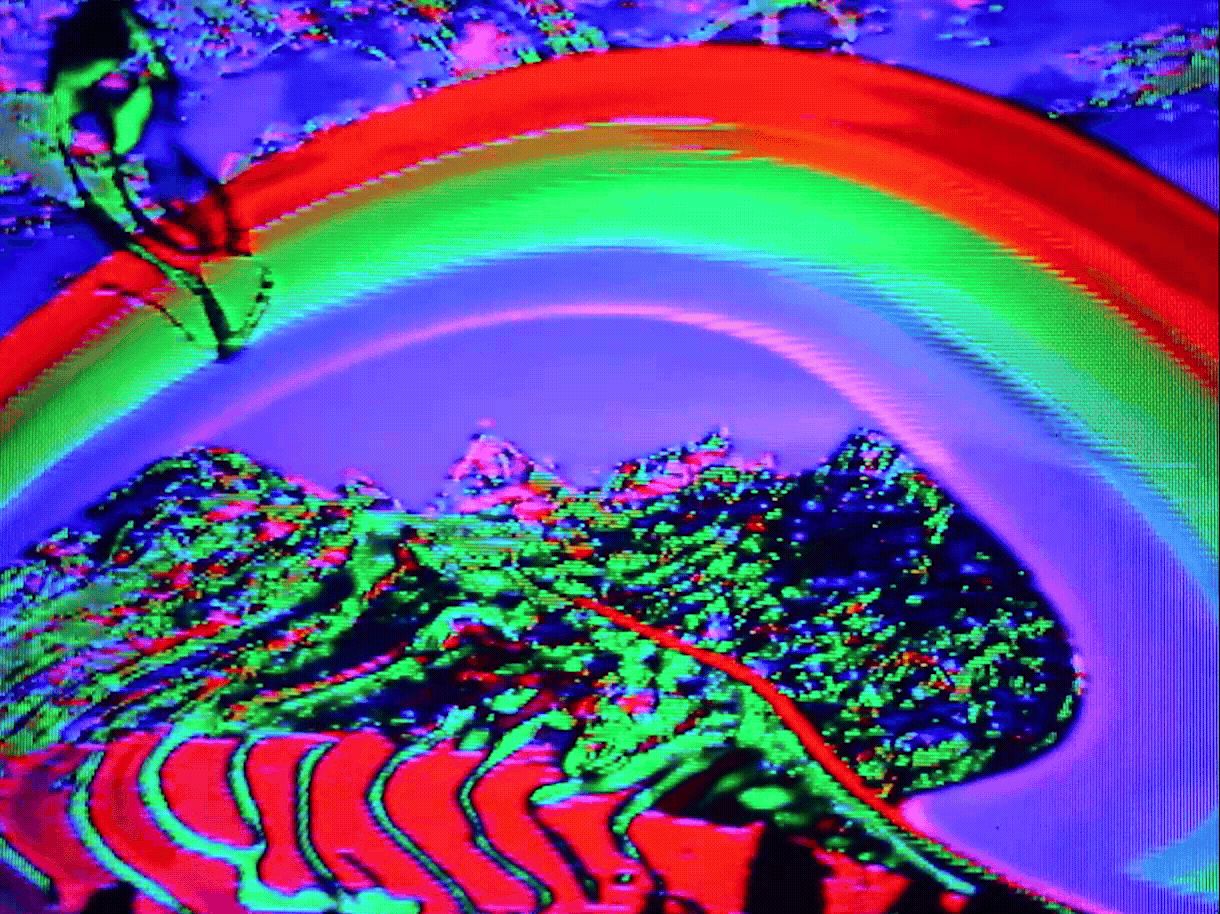

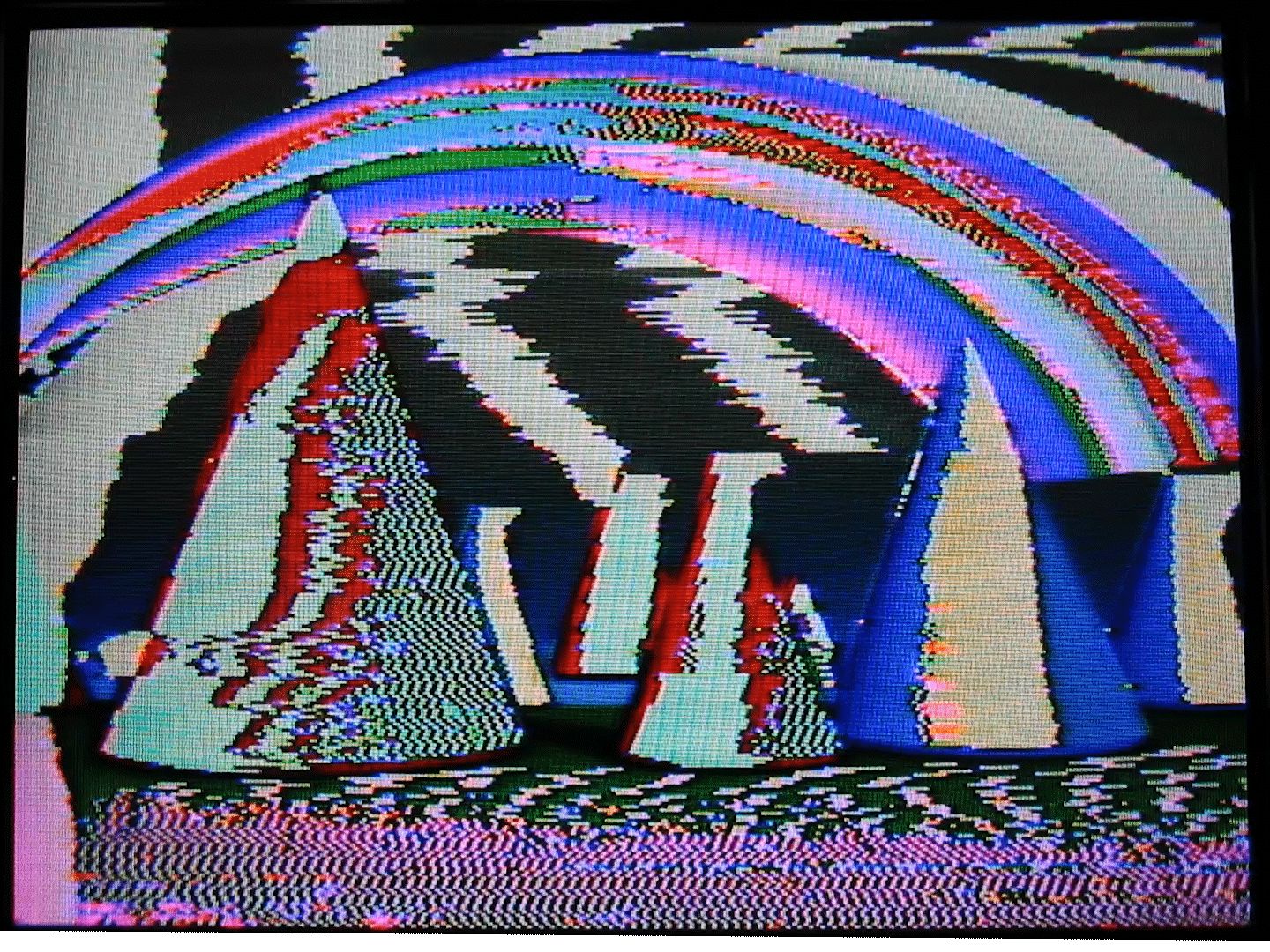

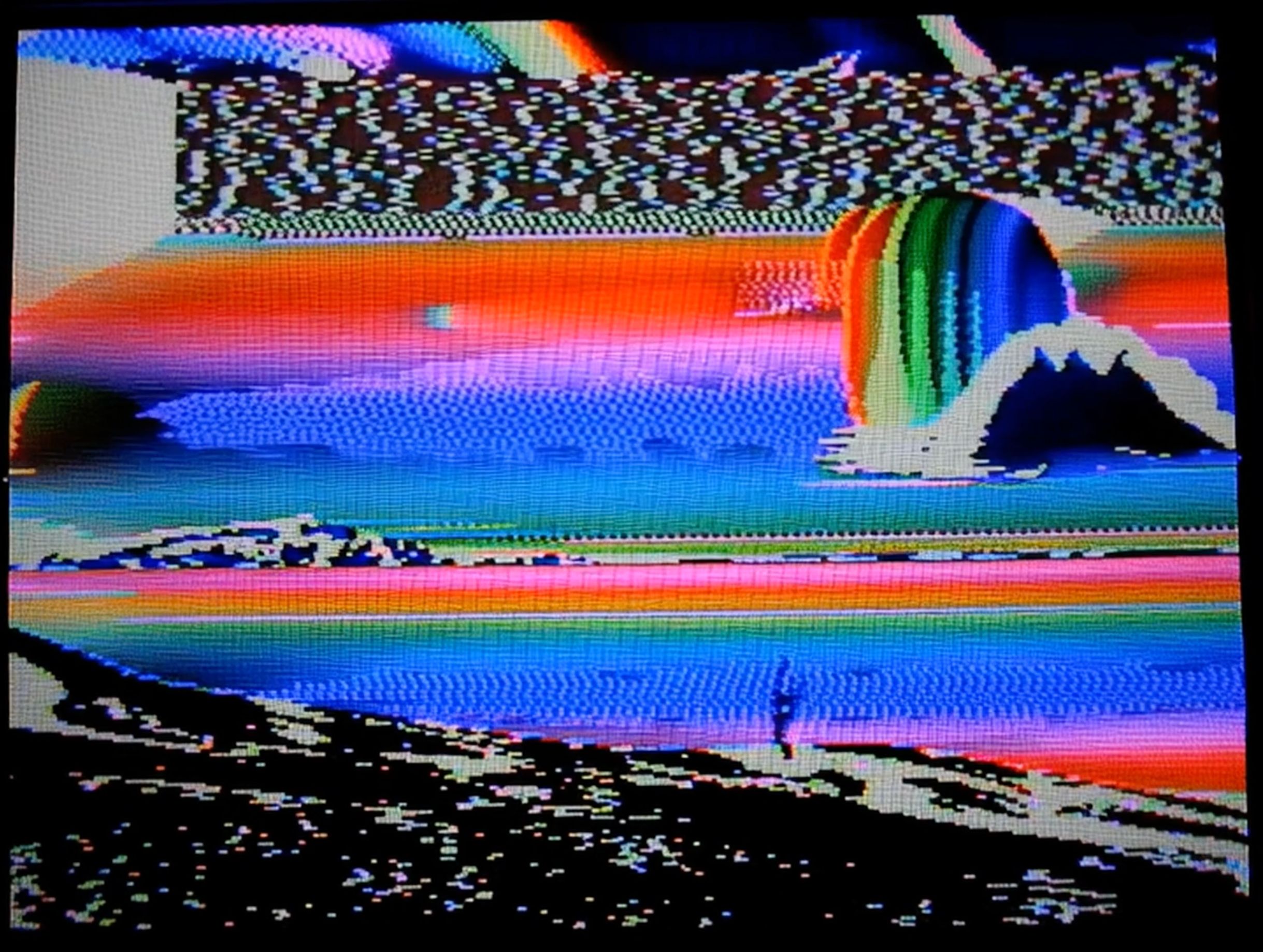

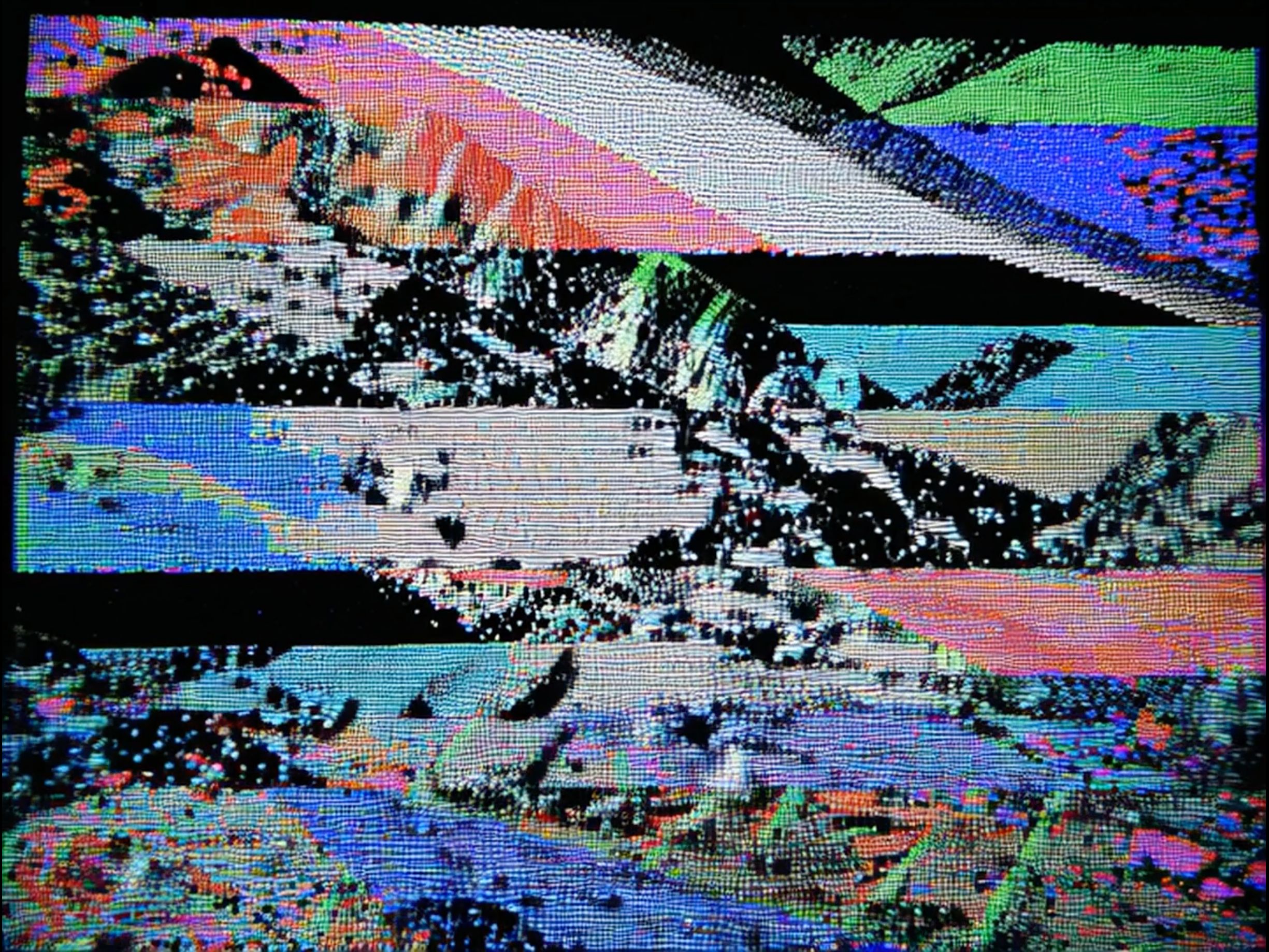

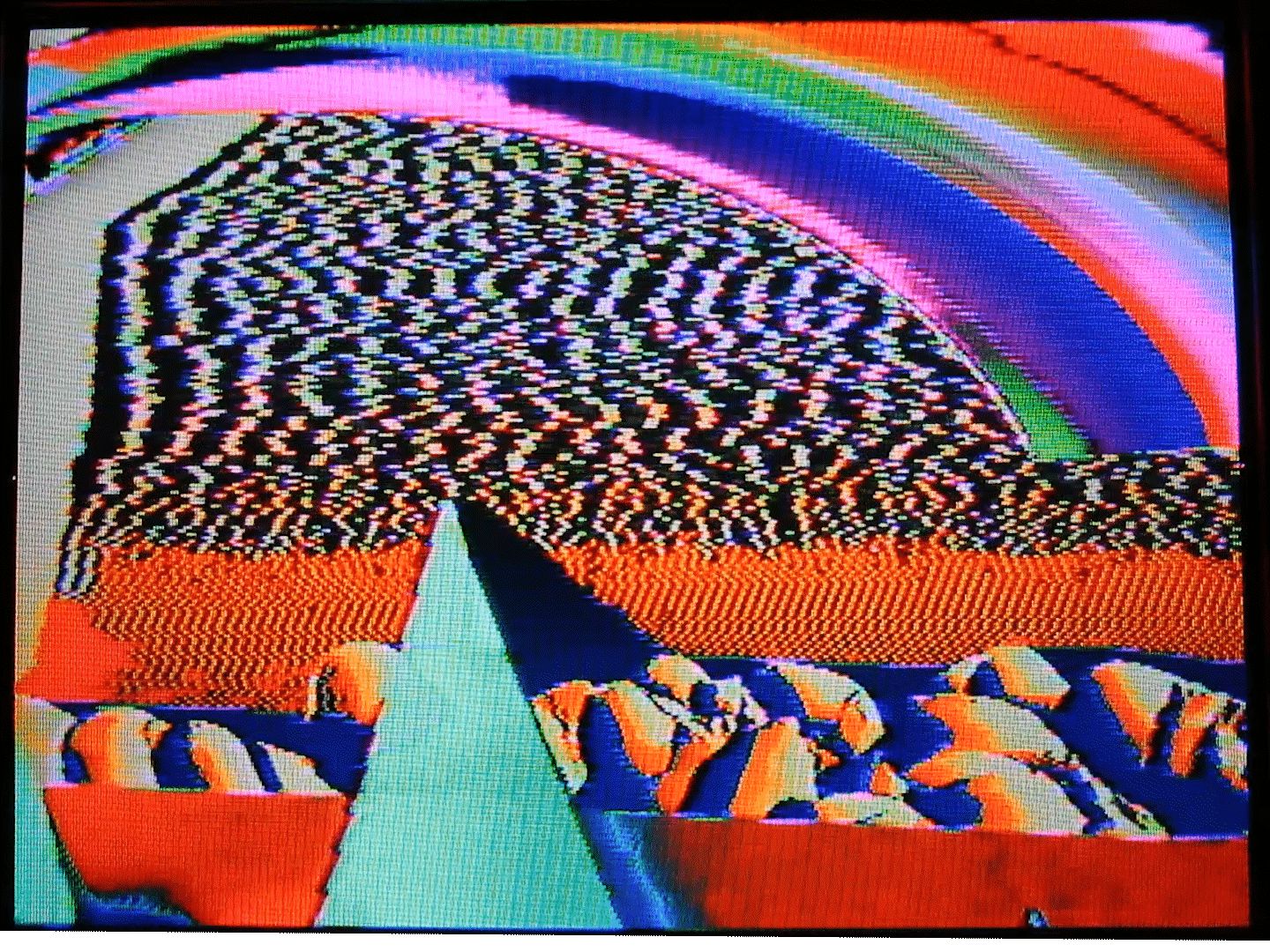

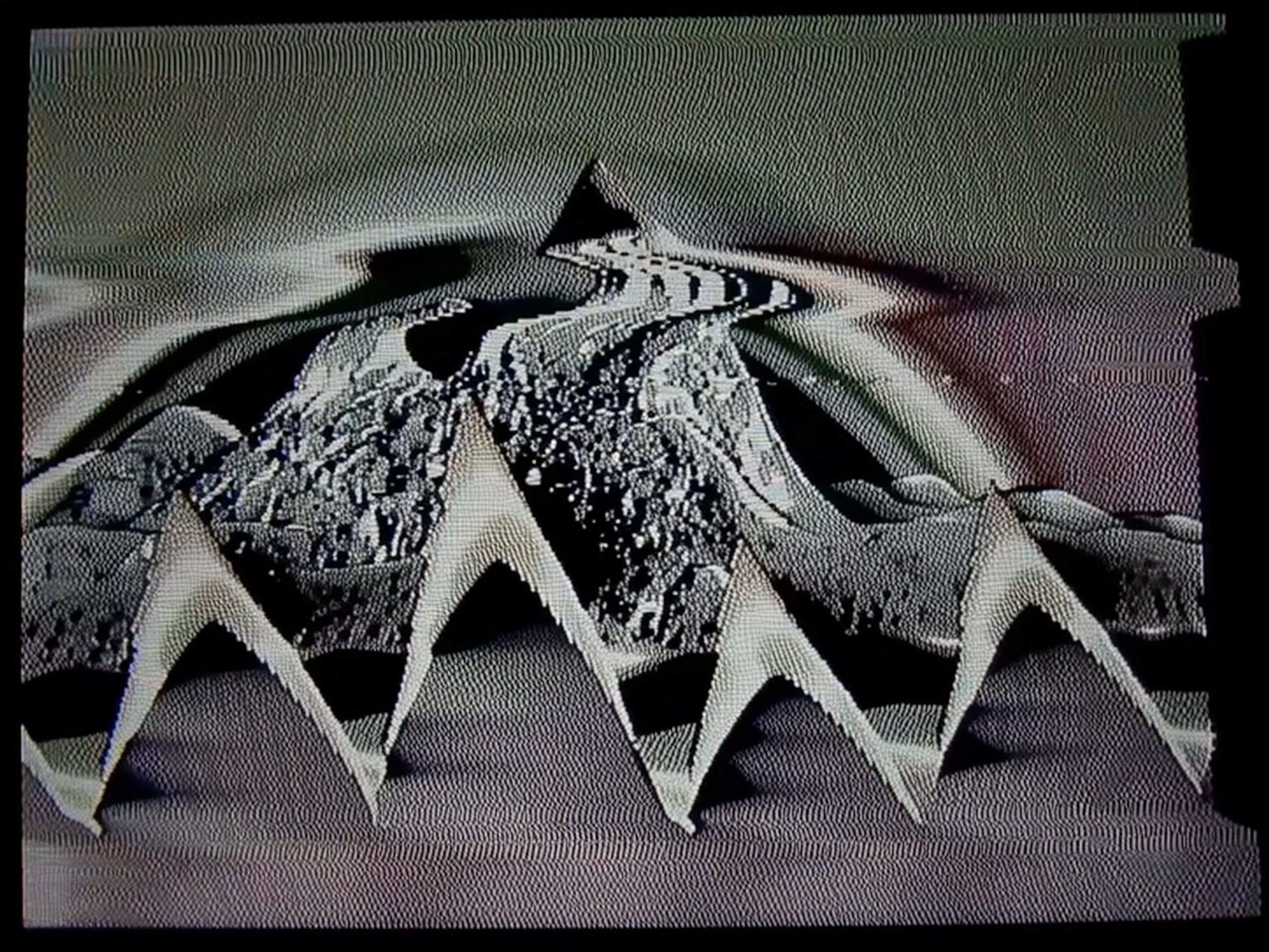

In this sense, we take our collaboration to be a long-distance dialogue between two ways of using the machine, of mediating landscape, and of inhabiting the world: computational swarms that synthesize video, and analog ensembles that manipulate images through cathode-ray monitor synthesis. Some of us in a forest, others in the monster-city. Then we realized a piece was missing from the landscape: if computers touch the world, they do so through us. So we began to exchange human footage as well—gestures, bodies, scenes—and, as the machine processes it, it “understands” that one path to synthesizing the world is to generate place: from the act of touching landscapes we move to generating faces by statistical distribution, and from there back to terrain.

Here we remediate explicitly: by remediation we mean the reconfiguration of one medium by another. In our case, computer-generated material is re-medialized via analog synthesizers and then returned to synthetic video generators. That to-and-fro circuit produces a collection of videos and GIFs as traces of the technical and aesthetic conversation between media. We take Tactile Studies of the Synthetic Landscape to be a synthesis of our practices, in the most literal sense, and a conversation about what we see and what we dream.

– Canek Zapata & Rocio Mio