Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Twitter Spaces: Harm van den Dorpel in Conversation with Nico Epstein and Leyla Fakhr

Nico Epstein: Thank you everyone so much for joining us on this lovely Friday evening. I am joined by my partner in crime, who is a terrible joke maker, a multilinguist, a great cook, and perhaps most importantly, Verse’s Artistic Director, Leyla Fakhr.

I am also joined this evening by Harm van den Dorpel, a new media artist who has gained recognition for his exploration of the intersection between artificial intelligence and artistic expression. He is known for his innovative use of algorithms and machine learning in his artworks.

His works reflect our unique digital age, questioning the relationship between humans and technology. In 2015 his work entitled Event Listeners was the first artwork acquired using Bitcoin by a museum, the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), in Vienna. He has had institutional exhibitions at the New Museum in New York, the Ulan Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, and the Steidelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

In the words of the critic Joseph del Pesco, ‘Dorpel's works are continuously evolving, informed by feedback loops and the design of algorithmic systems with immense skill and craftsmanship, he builds advanced systems… that draw on intuition and subliminal processes of the mind in order to continually output unexpected and curious aesthetic forms that embody a feeling of subconscious computation.’

Today we are going to be discussing Struggle for Pleasure, the first of our Verse Solo series of 2024. I have been particularly engaged with the complexity and beauty of this project in the way in which it touches on the avant-garde rhythmicality of the Belgian composer Wim Martens and other electro acoustic composers.

In fact, I myself have written extensively on Neo-impressionism, particularly Neo-impressionist musicality, and I'm not sure if you are aware of this but Paul Signac actually named many of his works Opus, which was a nod to the symphonic elements of the dots as part of the divisionist or pointillist techniques.

But maybe we'll get a bit more into those dynamics and comparisons later in our conversation. I wanted to start things off by asking you Harm to tell us a bit about Struggle for Pleasure.

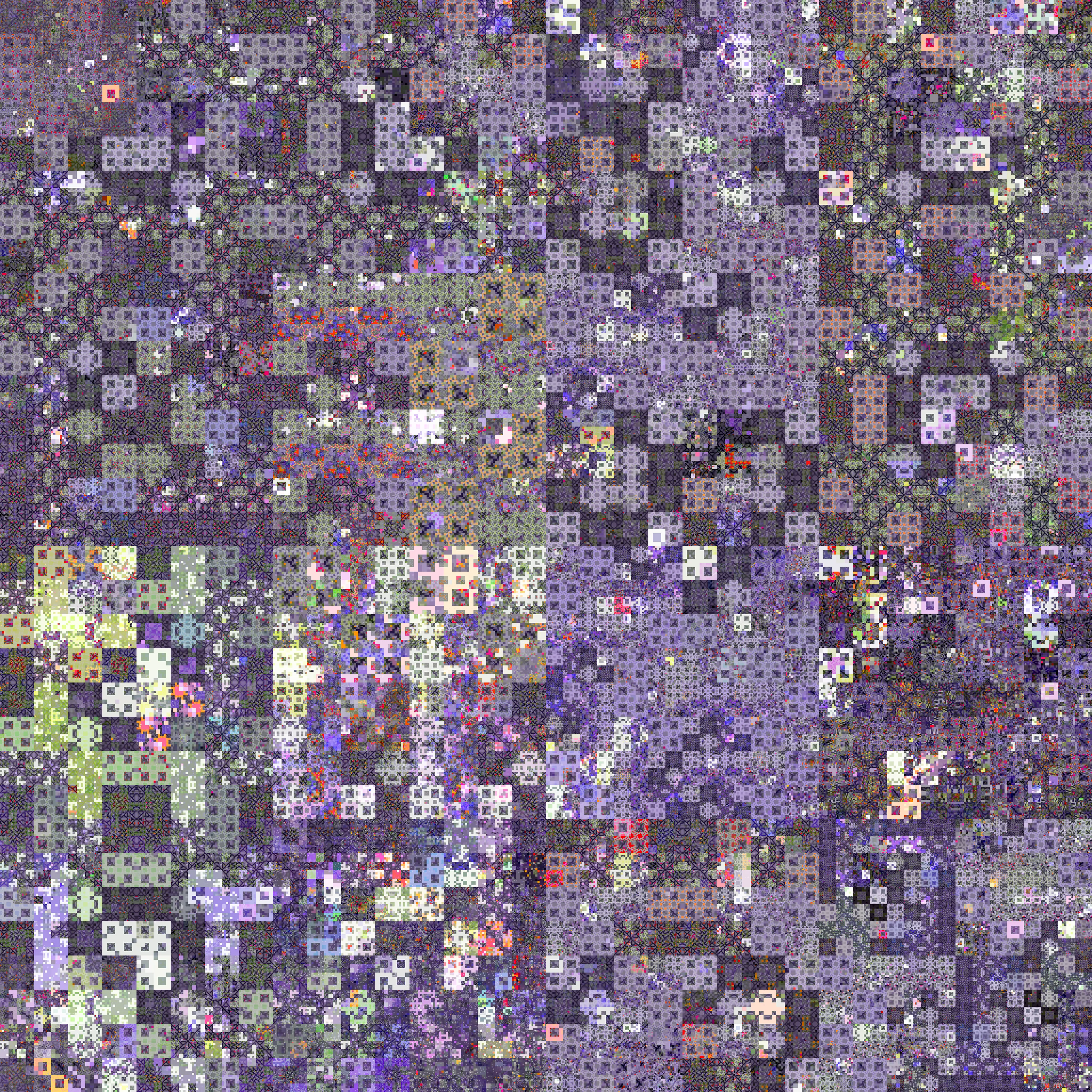

Harm van den Dorpel: Thank you for that humbling introduction. Struggle for Pleasure is sort of my first commitment to pixels. If you have seen my work, I've often used larger geometrical shapes that would refer to user interface design like Mutant Garden Seeder. As I was cranking up the resolution of those works, the components got smaller and smaller at some point, you couldn't really get smaller than a pixel. I was really hesitant because as much as a lot of famous pixel NFT projects, like CryptoPunks for example, are really interesting and important projects, aesthetically I felt always very far away from them.

I think a large component in the appreciation of pixels is that they refer to nostalgia for the early days of, let's say, computer games and 8-bit consoles, which is all, again, very interesting, but it was not my language. As I said, the resolution, the shapes, the components, the building blocks of the works got smaller and smaller until at some point I arrived at the pixel level, and I was also really interested in the variation of resolution. In particular, going from thinking about the computer games that I played when I was like young, you know Prince of Persia and Lemmings, which in my memory were detailed, beautiful games with lush graphics, but when I look back at screenshots of them, now they are so pixelated that we can barely imagine what they depict.

So I think what is at play with pixels is that our mind tries to interpolate the space between those pixels and construct more complicated entities behind those pixels. By varying the resolution of the pixels within one work, my eyes and my mind was jumping back and forth between feeling that I understood what I saw and constructing what I thought it would be. So this is what I wanted to convey in a way that wouldn't feel nostalgic.

Leyla Fakhr: It’s really interesting how you talk about pixels in that way, because, um, very often with abstract expressionist works or even figurative works I get most excited when I feel like I myself as a viewer can complete the image with my own imagination.

You mentioned previously that you feel like there is ‘pixel fetish’ going on at the moment, can expand a little bit on that?

Harm van den Dorpel: Back in the days when digital displays were of much lower resolutions, it was a necessity to express complex information only using the few pixels that were available. Nowadays, our screens have enormous resolutions, so to now display an image in that older lower resolution on a high resolution screen is actually not necessary, it’s mimicking something. In this new series I'm shifting back and forth in the animation between high resolution and low resolution, gradually increasing the resolution almost as if it's rendering the work.

Normally when we are rendering something or sharpening an image, we expect something to be revealed. In this case, the resolution is sharpening but nothing more is revealed. You don't suddenly see a meaningful image because it's fully abstract. In that sense, the low resolution pixels are as meaningful as the high resolution images. Something that came into play later which I didn't initially anticipate was how we are very used to pixellation (in videos of crimes or trademarked videos for example) being used to purposefully obscure and censor the image and it makes you want to see the image even more. There is a certain almost macabre fascination with the low resolution image, I think.

Nico Epstein: When I look at your Struggle for Pleasure works, I think about those images that I looked at as a child where I would stare at them very closely and be cross eyed, and then eventually a three dimensional image would reveal itself. I don't know what those are called, but you know what I'm talking about right, Harm?

Harm van den Dorpel: Yeah, the stereoscopic images. I know exactly which ones you mean, I love them too.

Nico Epstein: So, when I see one of these works, which are, let's say a bit more fuzzy in terms of their overall resolution, it reminds me of that in the same way that. When you're expressing your, your nostalgia for Lemmings and Prince of Persia, I think about Zelda, Duck Hunter, Super Nintendo, those types of games, all of this comes back. And I think that's part of the beauty of the series and the beauty of all great art, which is that you are able to string together points of reference from your own memory or your own childhood. I see a lot of that within this particular body of work.

When we're talking about these mnemonic references and and looking back at the past, I think we also have to consider the actual compositional integrity and the way in which these works come together as a whole. I wanted to ask if you could describe the sort of process behind the rendering of these works and how they come together compositionally, how you arrived at these final images.

Harm van den Dorpel: Yes, that’s a very good question, I can elaborate on that. In many of my NFT collections (and I think also those by other artists) which would be labeled as long-forms, I worked on my algorithms for a very long time. I think Mutant Garden Seeder from the very first inspiration to it being released was roughly two years. And during that process of creating the final, hopefully pristine algorithm in that process, I would discard outputs along the way because the algorithm wasn’t perfect yet.

Sometimes I did take screenshots of Mutant Garden Seeder, or I saved some of the SVG files, and later I thought that actually what I dismissed so early in the process was actually also a valuable image to me. And so I took a different approach in this case; I didn't really know in advance what I was going to make, except that I wanted to work on this mechanism of very different resolutions in one image. Then while I was programming and searching, each time I would make a little change, I would would store the highest possible resolution of that image to keep and gave it a timestamp. And then I would continue to see where it would bring me.

That also ties into the title of the show, because I mean, it's a struggle, there's always this uncertainty, but it was quite a pleasurable struggle because I love to program. You think, is this going in right direction? Is this any good? How will this be received? Should I quit? And so instead of dismissing all those steps where I stored everything and I just went on and on, continuing. So the series is a chronological overview of this process of programming.

So it's 128 tokens. I also colour balanced each image manually after rendering because I love to obsess on that and bring out more what I noticed in the image that could be good. So as a generative artist it’s like I’m completely cheating.

Nico Epstein: No, it's not cheating, it's a labor of love.

Leyla Fakhr: It’s appreciating. What I love about this is that you're really appreciating what the algorithm can offer and you really sort of shape it and play with it as a unique piece within a collection.

You mentioned that you included the timestamps and in a way the series is almost like a diary where we are part of your process. Can you tell us more about why that's been important to you?

Harm van den Dorpel: Yes, I decided to to have the date or the timestamp to be a property or a trait of the of the tokens. It started early December/end of November last year and I completed the last ones only recently.

In my old works where I would work towards one final algorithm I could program as long as I wanted, and still I see an image and I think, ‘Oh, it would be nice to make that red a little bit more red’, or ‘I don't like that green in that image’, but to program the changes means to some extent that the change will also be applied to all the other images that are generated by the same algorithm. So I used a sort of hybrid that meant I could fine tune the images in a feedback loop of generating works, changing the algorithm, generating more works, curating the outputs, manipulating them.

I don't only use Photoshop, I also have other command line tools to tweak images. It's not this hermetic approach to prove I can make an algorithm that does this all automatically, I'm actually really not interested in automation.

In that sense I also have a complicated relationship to programs like Midjourney, I mean, I love them and they're amazing tools, but that thing that I'm not able to program is exactly the thing I want to emphasise. It is a certain human touch, which sounds really old fashioned and cringe almost, but to have this serendipity and these mistakes or things I don't imagine at first, I then focus on them and exaggerate them in post production and in Photoshop.

Nico Epstein: It’s fascinating to hear someone speak so cogently about the mechanics behind the production process when many artists in the space are not necessarily inclined to discuss their use of AI tools or their use of different frameworks. For me, listening to you discuss the way in which the works are made, so coherently and eloquently, is a breath of fresh air.

So, you’re not new to this space. You've been making works that engage with cryptography, tokens, Bitcoin etc. since long before the 2021 crypto summer. You’ve lived through this hype cycle, but you were also making work that addressed NFTs and Bitcoin long before it happened. Do you feel as though the space has evolved from when you started to explore the idea of Bitcoin to where it is now, with the Bitcoin ETF and the media cycle? How have you seen the space evolve when it comes to the way in which you make work and where do you see it going from here?

Harm van den Dorpel: You are right, I’ve been making these images for a while. I graduated from art school in 2006, but I started programming when I was around 12 years old. Initially, I didn't have the ambition to be able to live off making images. In 2008 all the work was online on blogs, and we would post with friends and respond to each other's works and everything was available for free, for all. There was no connection to the art world and there was no expectation that it would ever make money.

When I first encountered this idea that you could store ownership on a decentralised ledger, I thought maybe that's interesting. That was in 2015, and I started this online marketplace Left Gallery with my partner and we occasionally sold something. At that time the artworks were maybe only 30 euros, and people were really hesitant to buy, which is always funny because people don't hesitate for a second to buy a cocktail or three in a bar, but then buying digital artworks is difficult.

So we had this online marketplace where we produced we called them ‘downloadable objects’, and people would be sent a sort of a proto-NFT to their wallet. I never had the idea that this was going to change the world, I just thought it would be an interesting proposition to see if that would work.

For a long time it barely worked, and then suddenly, like you said, in 2021 a great hysteria broke loose. At that time I had a bit of a hard time relating to because I was thinking, we've been doing this for a while. Why is everybody now suddenly interested?

Nico Epstein: Because of money Harm, because of money.

Harm van den Dorpel: Yeah, yeah. And that was okay for me, because if people were buying for speculative reasons, I was benefiting still from royalties, which really kept it fun. And now that royalties are, well, at best they're optional now, but they're pretty much ignored, that’s made me a bit disappointed with the space. Even though I knew, like you said, it was about money, I also thought it was in large part a genuine love for art. Of course there are many, many true collectors, but this new reality can be a bit of a downer.

I have been making digital art for a while and regardless of the adaption of platforms, I will make work until I die. It doesn't really influence me. But let’s not to dive into the royalty conversation, it’s one for another time.

Leyla Fakhr: So going back to what Nico was saying, you've been making work obviously for a very long time and very often you are described as a post-internet artist. How did you go from being a net artist, to becoming a post-internet artist, to being a video artist, and what do you think about all these definitions, and how you would define yourself?

Harm van den Dorpel: That's a good question. I go back to that time when I was at art school and online publishing, and the net art rise played a big role when me and my peers who were only publishing online were suddenly then also asked to show our work in gallery spaces or museums. It was great honour, but it also felt a bit weird because we made internet art to specifically comment on that context of the browser of your devices, so to suddenly project that work into a space it became about other things. So, I think me and some of my peers took the same mindset from commenting on the context of the internet, to instead commenting on the context of the gallery space.

Suddenly when you are in museums and galleries, there's also an art market. When some of these net artists became post-internet artists, they made sculptures. I'm totally guilty of making sculptures myself as well. I loved it. I still do, actually. And I think that's what post-internet is. It’s not that the internet is over, but it is the sort of mindset from this internet generation expressed with material in a gallery space. I got sort of deep in that movement, but then I also started to miss my programming roots and went back more towards making art online.

Nico Epstein: It’s funny how people got caught up on the label of post-internet art. It’s also funny how a lot of the artists in that space who had that label applied to them are actually no longer artists at all. For example, Artie Vierkant wrote his seminal essay, ‘The Image Object Post-Internet’, in 2011 or so, very early on, and he no longer makes work at all. So the fact that you've persevered through these various movements is a testament to you as an artist. With that in mind, I wanted to ask about the physical nature of the works, the resolution paintings, and also this particular series Struggle for Pleasure.

If we're looking at the renders, they could easily be applied to some sort of dibond mount, some sort of photographic display or exhibition display. Thinking about Artie Vierkant's work a long time ago, he was making works that were displayed in gallery spaces. They were actually stainless steel cutouts and then they were blurred in Photoshop and we couldn't tell which was the actual artwork and. In your case I think you've made it a clear distinction between the on-chain media and the works that have been displayed at Upstream and resolution paintings in the other series. So for Struggle for Pleasure, what methodology makes it distinct as something that's a digital format as opposed to something that is actually a physical object, which a lot of your work is.

Harm van den Dorpel: It took me a long time to find a way to materialise high resolution images. And I love it when they are materialised because the resolution of modern day manufacturing methods is insanely high. And the colours are difficult, often printing things is really hard. I spent a lot of time and made a lot of mistakes in seeing or experiencing that what works on the screen doesn't necessarily work as an object. So I settled on a technique that is actually photographic. The works in the upcoming show are not printed, but it's a photo photographic process where the image is exposed on sensitive photosensitive paper and then mounted. So they are pretty close to the colour space you can have on a screen, and quite often people don't actually really believe that they are not screens. I quite like that. With a very thin frame, it’s almost like it's a tablet.

I don't need it to be identical to the screen, or the opposite actually, it's very different, but what is also important to me is that they can be hung next to an oil painting. I have this desire to understand images and understand the world through images, and it’s very insightful to curate works by different artists from different times and have them hung next to each other. It is kind of taking a step towards other eras and almost like an anachronism that I make these things to see if they hold up next to an oil painting.

Maybe I just always wanted to be a painter.

Nico Epstein: I would say they do hold up within the overall sort of canon, not just in relation to Neo-impressionism, but also op art, and also pixel art. What I think is so unique is that this particular body of work straddles that art historical precedent, but also speaks to the crypto punk culture and the video game culture and all these other artistic visual movements.

You mentioned music; there is a certain rhythmic element in your work. I think, synesthetically, we associate a sort of moving pixel or a dot, dot, dot movement with a certain sound. When you're engaging in the formulation of the image, do you have a certain music or rhythmic structure in mind that the pixel formation or the patterns then adhere to?

Harm van den Dorpel: First of all, and this is maybe a provocation, I think music is the highest form of art. I say that because music can, by employing purely abstract, structural compositional rules and methods, create this delicate tension between repetition and variation, and it can bring me to tears.

Music has this very emotional capability, while at the same time, it is also very cerebral. And I'm a great lover of Johann Sebastian Bach, and sometimes when I listen to music in bed and I hear part of the Johann’s Passion and I cry and I think, if I would have to die now, it would be okay. I’d rather not, but it would be okay. And I just hope that with something like pixels, I can make some kind of image where I lose myself and where the viewer can lose themselves and sort of have a transcendental, ecstatic experience. That's a very big thing to ask. There's a lot of melancholy, I think.

Leyla Fakhr: You speak a lot in your work about consciousness, and I wanted to ask you how that comes into play in your work. I've been chatting to you for a couple of months now, and you are an incredibly thoughtful person, you’re very mindful of your environment. I wanted to ask you more about that consciousness, in particular with your recent exhibition that you also had in Amsterdam at Upstream Gallery, Our Inner Child, how do you marry together the very personal aspects of yourself, with a medium that perhaps doesn't always lend itself to that?

Harm van den Dorpel: Well, thank you for the question, it’s a big compliment to get that question. I think because I started programming relatively young the medium has always been accessible to me. It is very important for me to make digital artworks that do not try to prove their technological skill, I don't want to impress with technology.

I'm very inspired by the medium as a way to get to this escapist or transcendental experience. The show you mentioned in Amsterdam actually came after I had a traffic accident and I'm all fine now, but I had to make the exhibition in bed because I had to rest. The ‘inner child’ therapy is something very powerful, I find. My background is a very religious background. My father used to run a church. And so there has always been this complication of finding my own way in life really, and making work has always been my safe beacon in the right direction, if that's an answer.

Leyla Fakhr: That’s interesting. So am I right to think that your father, was he a stockbroker, but also running a church?

Nico Epstein: Church of Commerce?

Harm van den Dorpel: Yes you were right, he was working on the stock market until he converted to evangelical Christianity around my 12th year, around the time when I started programming.

Nico Epstein: Would you say that there's something intrinsically Dutch about your form of making? In the press release for Our Inner Child it mentions Mondrian, Van Doesburg, and you can see the sort of still format that that comes about from using a grid like formation. Is that something that you that you feel is inherent to your practice or something that you associate with?

Harm van den Dorpel: Yeah. Well, I once had an exhibition in Italy. I think it was in 2010, and an Italian said, ‘Harm, you're such a Dutch artist.’ And I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ But then I have a background in graphic design, Dutch graphic design, and I used to teach graphic design. So, yeah, the influence is there. It's also the things I would see as a child in around me, and it's only maybe more recently that instead of pretending I wasn't aware of that, I started to look at whether that is something I can like broaden or deepen. But one thing in this Dutch modernist tradition is that there's a sense of determinism. Mondrian would obsess for a long time, I think, about how a particular composition would have to be, but for me it's actually the opposite. I generate things at random, or I breed generations, and then I curate and manipulate. It's very different, I embrace undecidedness. And I think in the modernist tradition they're more deterministic.

Leyla Fakhr: I really loved seeing your work in the Stedelijk Museum next to Mondrian, I thought that was such a powerful display. As you were saying just earlier, you’d hoped to see your work sitting next to an oil painting and that's exactly what happened. It was a powerful image that I cherish very much, and I thought it was also a really bold move from the curators at the museum. It's interesting because you're an artist who navigates between the ‘art world’ and the ‘Web3 world’. Do you find that there is a strong division between the two or do you feel comfortable in not necessarily being in one world or the other.

Harm van den Dorpel: It's just the process and context and requirements for artworks that's just so different in web3 and museum contexts, how works are acquired and how they are consumed. I do change particular works for their appropriate context, but at the same time I also think that it's all fluid. I'm ambivalent about it. I mean, I rarely go to cinema because I always say I want to watch movies at home, but then when I'm in cinema, I think, oh, this is an amazing experience.

Nico Epstein: Besides Belgian electro acoustic music, what are some of your day to day inspirations, either consciously or unconsciously, are you big into op art or other artistic movements of the past? How do you navigate the new media of the world we live in?

Harm van den Dorpel: I listen to many different things. I live in Berlin and one of the reasons I moved to Berlin is because it has a electronic music scene and I love to go raving to concerts, and the people I hang out most with are indeed in the electronic music scene in Berlin.

Nico Epstein: Are you a Berghain guy? Panorama bar?

Harm van den Dorpel: I'm a Berghain guy, yes, but maybe more Panorama. It depends, it depends.

So, I like a lot of dead painters. I like Dieter Roth. I think if there's one artist that I feel really close to, it's Dieter Roth. I like Sigmar Polke, Seth Price, Hilma af Klint, and I like to go on Twitter, but it’s hard to keep up.

Nico Epstein: It’s hard to keep up. I find it's just a bombard of information and everything's changing very rapidly in the crypto space from month to month and week to week.

Harm van den Dorpel: There are two artists that I would like to mention who inspired me to dare to go into pixel art, Jeffrey Scudder and Travess Smalley.

Nico Epstein: Travess Smalley was one of the shows that we did early last year on Verse as well. Amazing.

Now, we’ve been talking a lot about Struggle for Pleasure, but are there any other projects or ideas in the pipeline for you that our listeners should know about tonight?

Harm van den Dorpel: It’s going to be a very busy year. I will have a completely different kind of work at the end of February in Paris with Bright Moments, and there will be an institutional museum show that is very important for me.

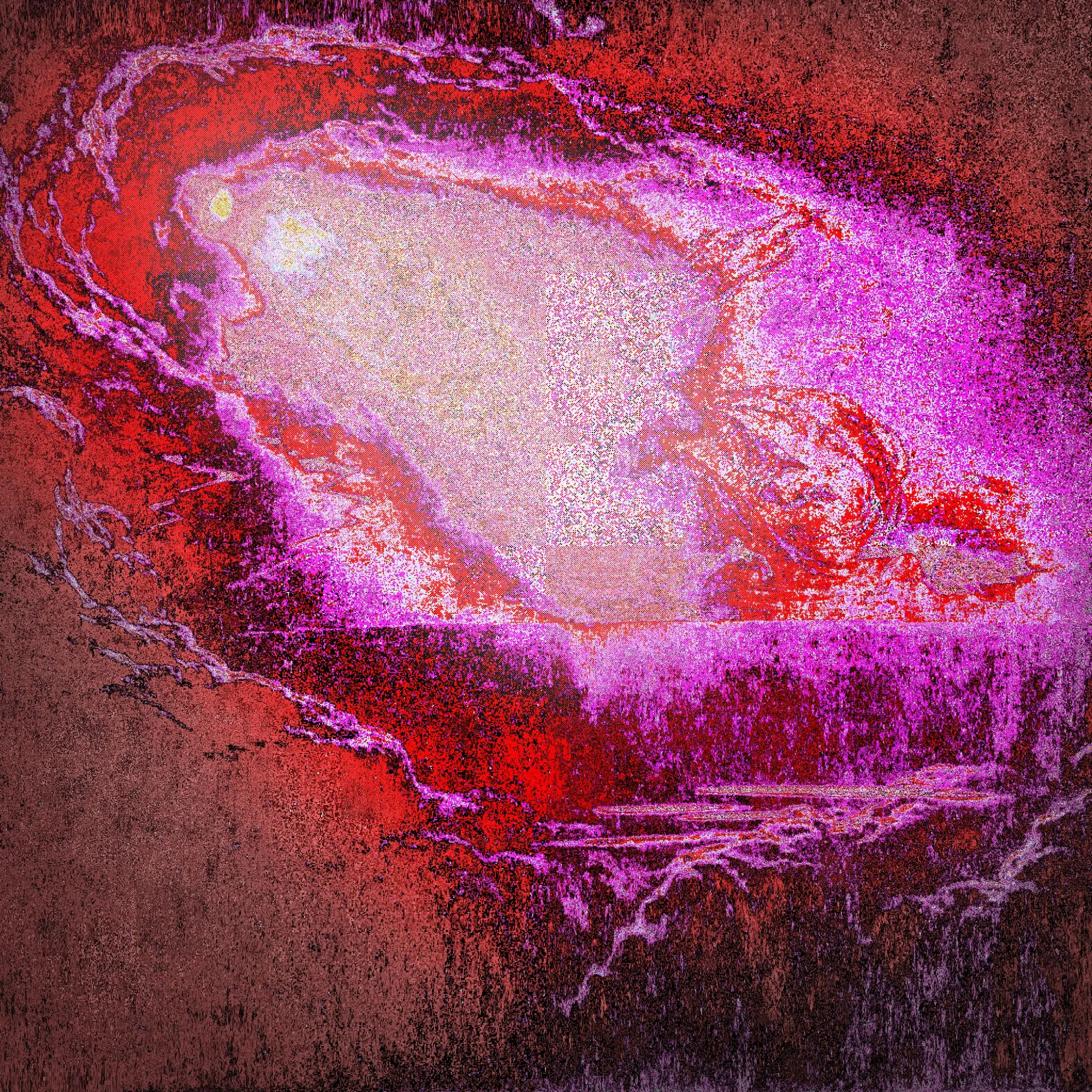

I'm really happy also with that there's this other series that came out of the fully algorithmically generated series, Struggle for Pleasure, which is also sort of playing with the mechanics of different resolution of pixel images, but then I started feeding it found images, and that is a new direction for me. I used to do that years ago, and I would also do that live with an electronic music ensemble. That sounds very serious, but so I'm glad I found a way back to connect my older works to processing existing bitmaps.

Leyla Fakhr: It’s really exciting. In your second series, Swallow, Only Shallow, which we're also showing at your exhibition Struggle for Pleasure, you're feeding in images of music albums that have been important to you and they're beautiful covers. So much thought goes into what people decide to make their cover, especially if it's done well, and there are so many iconic ones that for our generation that really stand out. I think with these particular ones, what is exciting is that you're bringing actually in an element of figuration into your work, which is something I hadn't seen before in the digital images you have been releasing.

Harm van den Dorpel: It’s actually more video stills from that era than album covers, but of course the album covers from that time share aesthetics. In particular I am interested in shoegaze music, so perhaps the most famous band in that genre was My Bloody Valentine. They’re just like rock bands, they have a guitar, bass, drum kit, and they're singing, but with shoegaze it's almost as if the band is there only to supply signals for this half heavy signal processing chain, where the texture and the complexity of the harmonics is created by using lots of delays and echoes and all these other effects to create new textures.

It's nice that Nico mentioned synesthetics, because the texture of sound is something I can really relate to. That's why in particular I'm interested in shoegaze music. And for people who don't know the name shoegaze, it comes from the fact that many shoegaze musicians, in particular the guitar players, would be so involved with their guitar effects that were situated on the floor that they would be staring at the floor all the time, shoegazing. Was that a dad joke?

Nico Epstein: It’s a funny descriptor. Now everybody's shoegazing for the Golden Golden Globe celebrities and shoegazing for consumer products. On that note, let's shoegaze no longer unless we're listening to amazing music, and let’s open the floor to any questions

Q: Thank you guys so much for that conversation. I wanted to ask you Harm, how you feel about on-chain works versus off-chain works. I know that a lot of your past works have been very responsive and inherently on-chain, which differs from these series you're releasing with Verse. How do you see the differences and how does it relate to your work?

Harm van den Dorpel: So for example, Mutant Garden Seeder is a native crypto project, which was very much taking the mechanics of the blockchain as the subject matter of the work. And in this project it's about this idea of painting in a way, and all the manual, post-production steps I took which could not be easily defined in code. In this case, the works are on IPFS and so to some extent they are also on-chain. I will also make the software that I build to create the images publicly accessible, but all the steps I took after that were once in a lifetime, I would not be able to reproduce them. I think blockchain can be a medium, in particular, the unique possibility of it is immutability. We didn't have that before the blockchain. Projects can have varying degrees of immutability, and this project is more about the particular image.

Nico Epstein: Well thank you everybody for being here on a Friday night, and thank you Harm, we’re so looking forward to seeing you on Verse very soon.

Leyla Fakhr: Thank you so much, Harm. It's honestly an absolute honour working with you. We can't wait to welcome you in London.

Harm van den Dorpel

Harm van den Dorpel is an artist dedicated to discovering emergent aesthetics by composing software and language, borrowing from disparate fields such as genetics and blockchain.

Van den Dorpel's work has been exhibited in the collections of, among others, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, MAK Vienna, Victoria & Albert Museum London, and ZKM Karlsruhe. Selected (group) exhibitions include the New...

Leyla Fakhr

Leyla Fakhr is Artistic Director at Verse. After working at the Tate for 8 years, she worked as an independent curator and producer across various projects internationally. During her time at Tate she was part of the acquisition team and worked on a number of collection displays including John Akomfrah, ‘The Unfinished Conversation’ and ‘Migrations, Journeys into British Art’.

She is the editor...

Nico Epstein

Nico Epstein is a curator, art historian and art advisor with a deep interest in digital art. He has helped to build two art tech businesses (Artvisor and Artuner) and has arranged more than 20 exhibitions of contemporary art throughout Europe, New York and Hong Kong, focussing mostly on artists of his generation.

He is a frequent lecturer on contemporary art at Christie’s Education in London...