Your Land

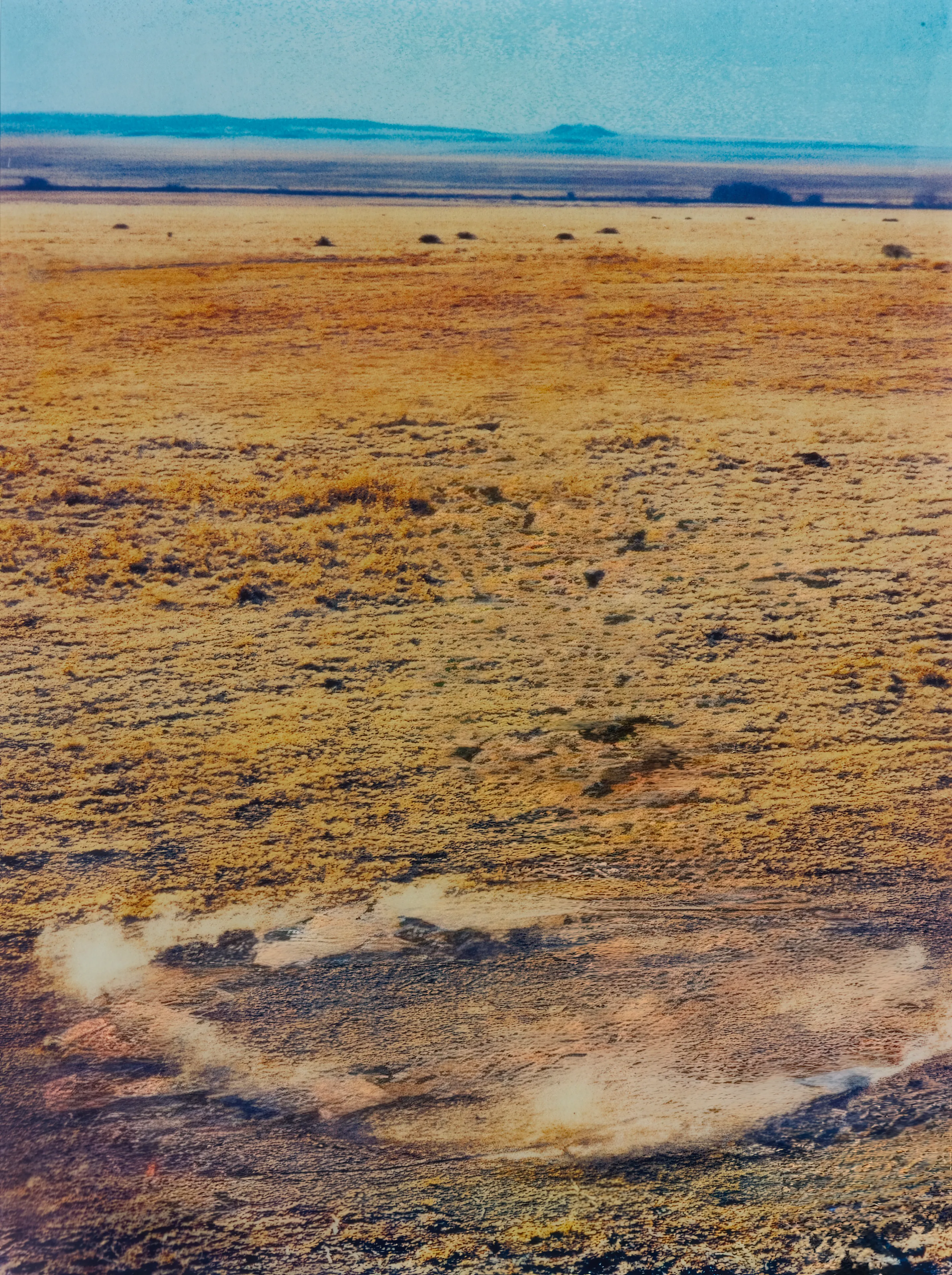

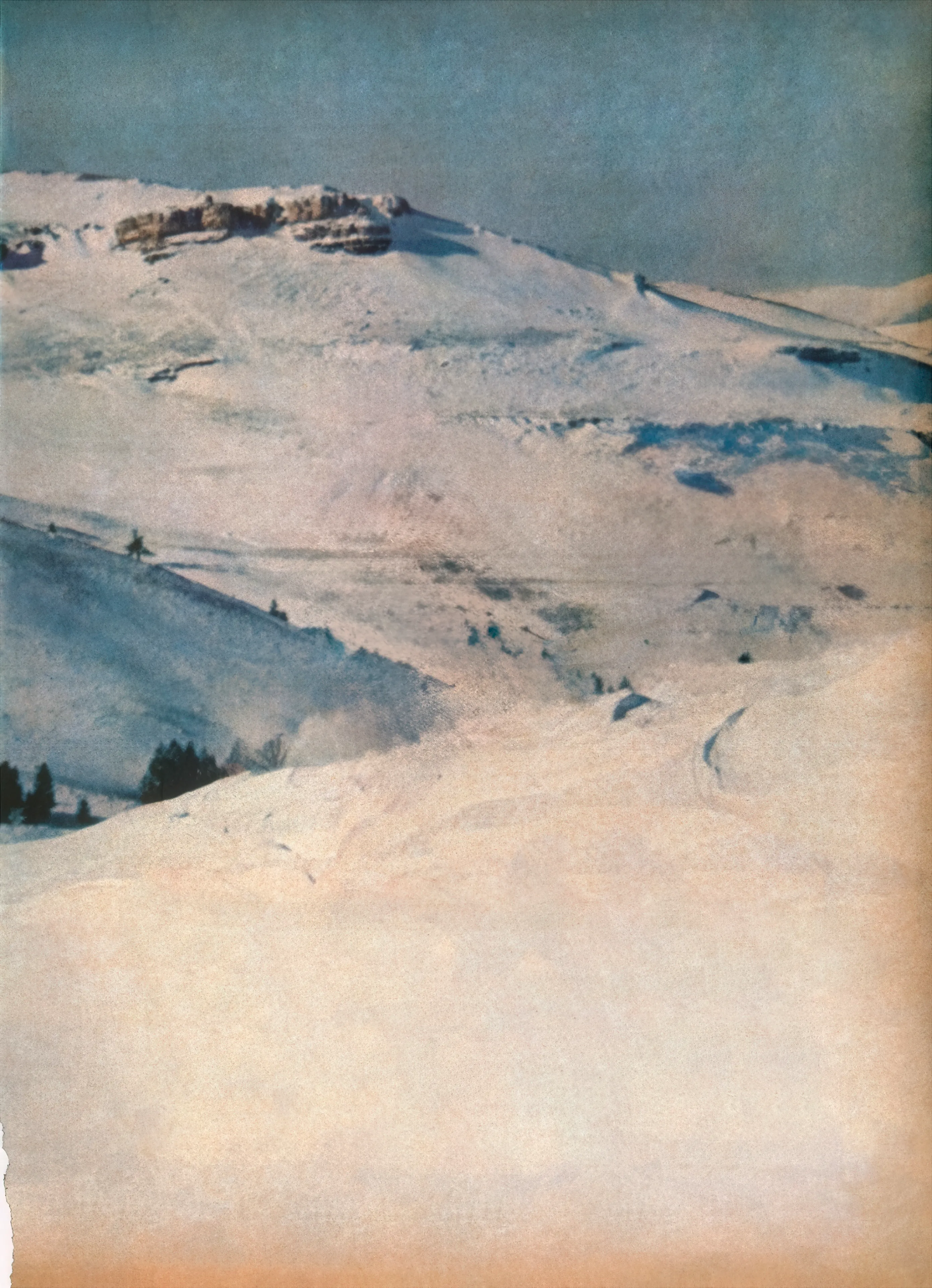

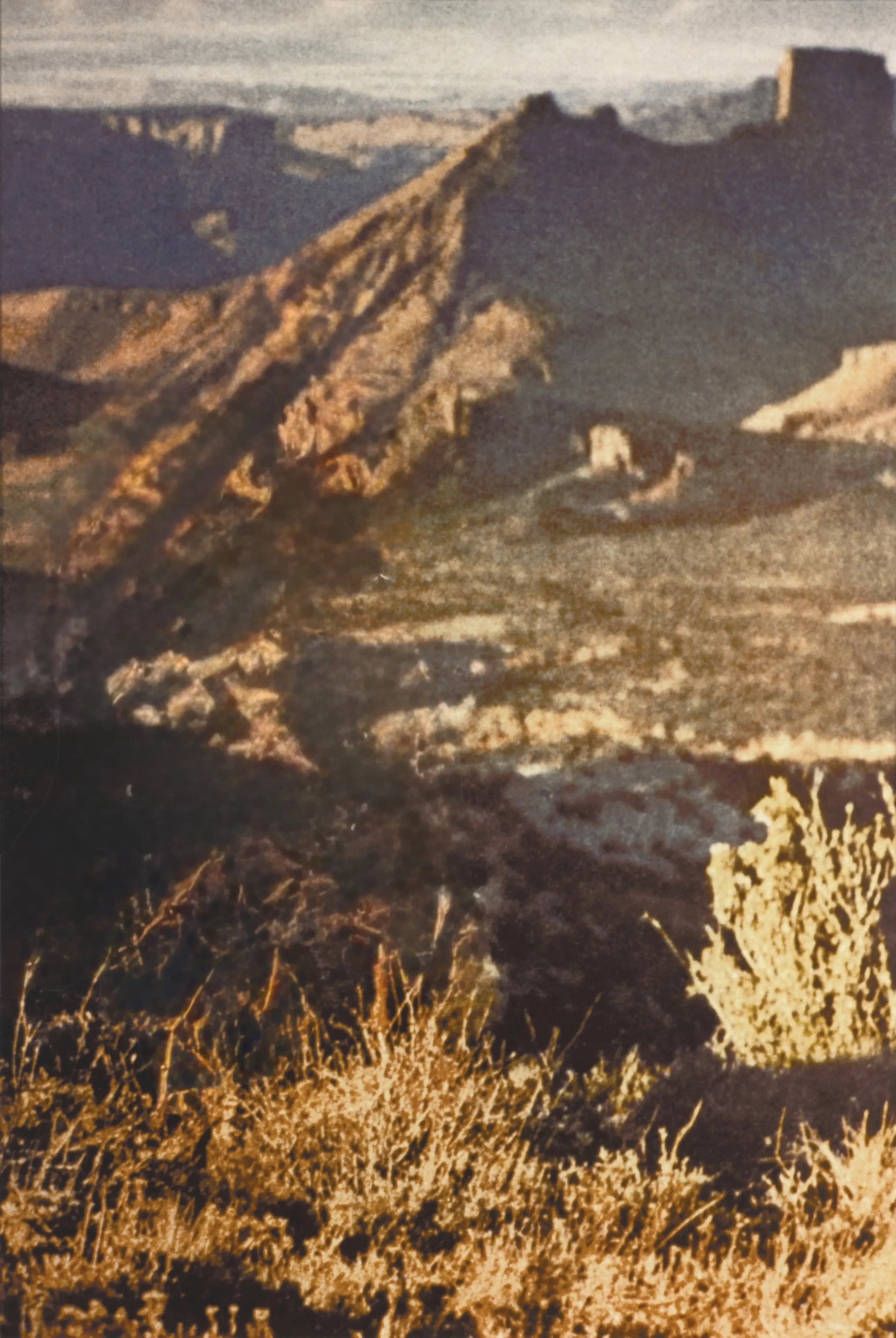

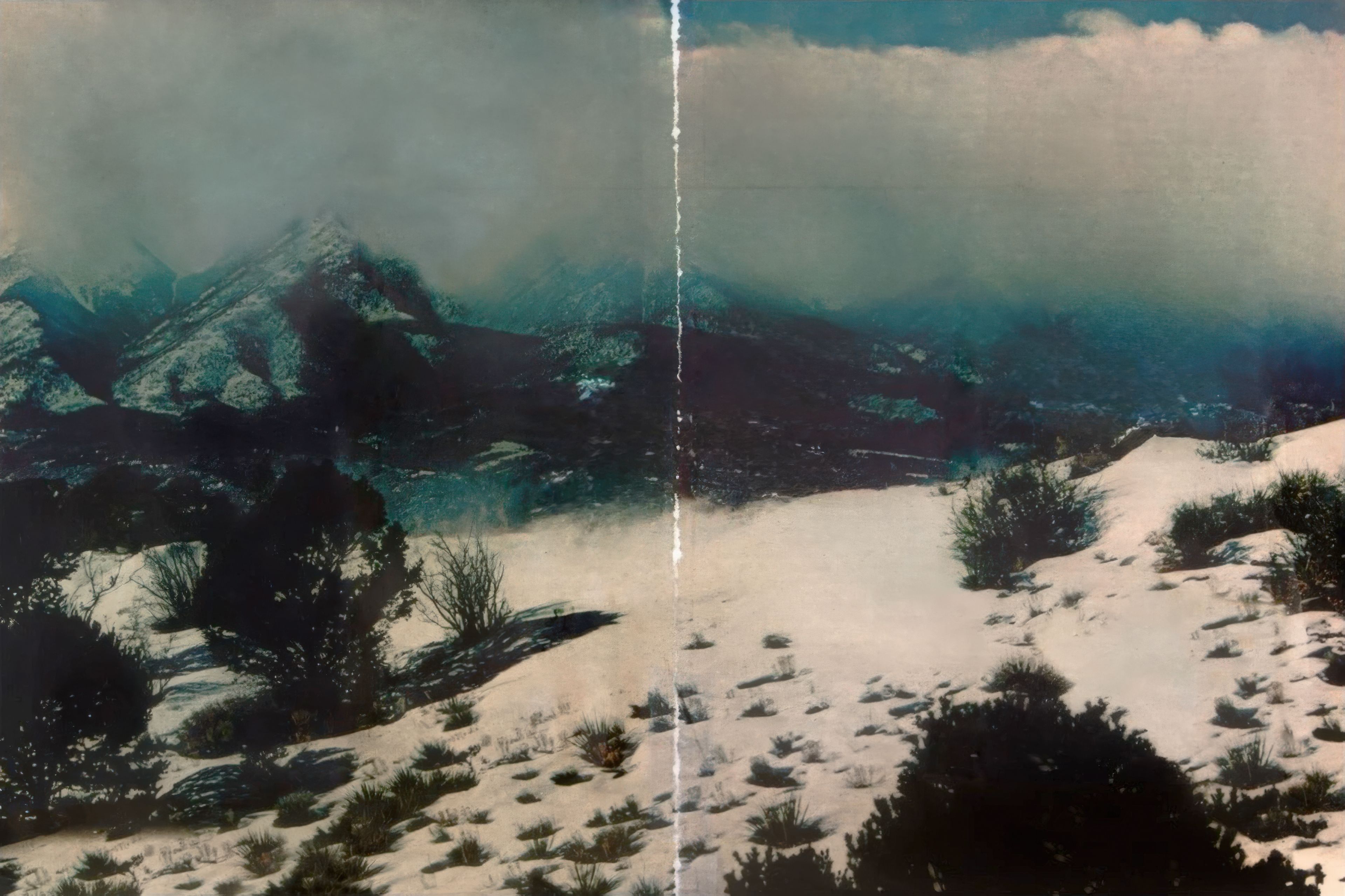

Michael Neff’s Your Land transforms Richard Prince’s iconic cowboy photographs into quiet, uncanny landscapes. Using ubiquitous consumer tools intended to clean up personal snapshots, Neff removes the mythic figures at the center of Prince’s appropriated advertisements. What remains are vast skies, empty terrain, and further questions about authorship.

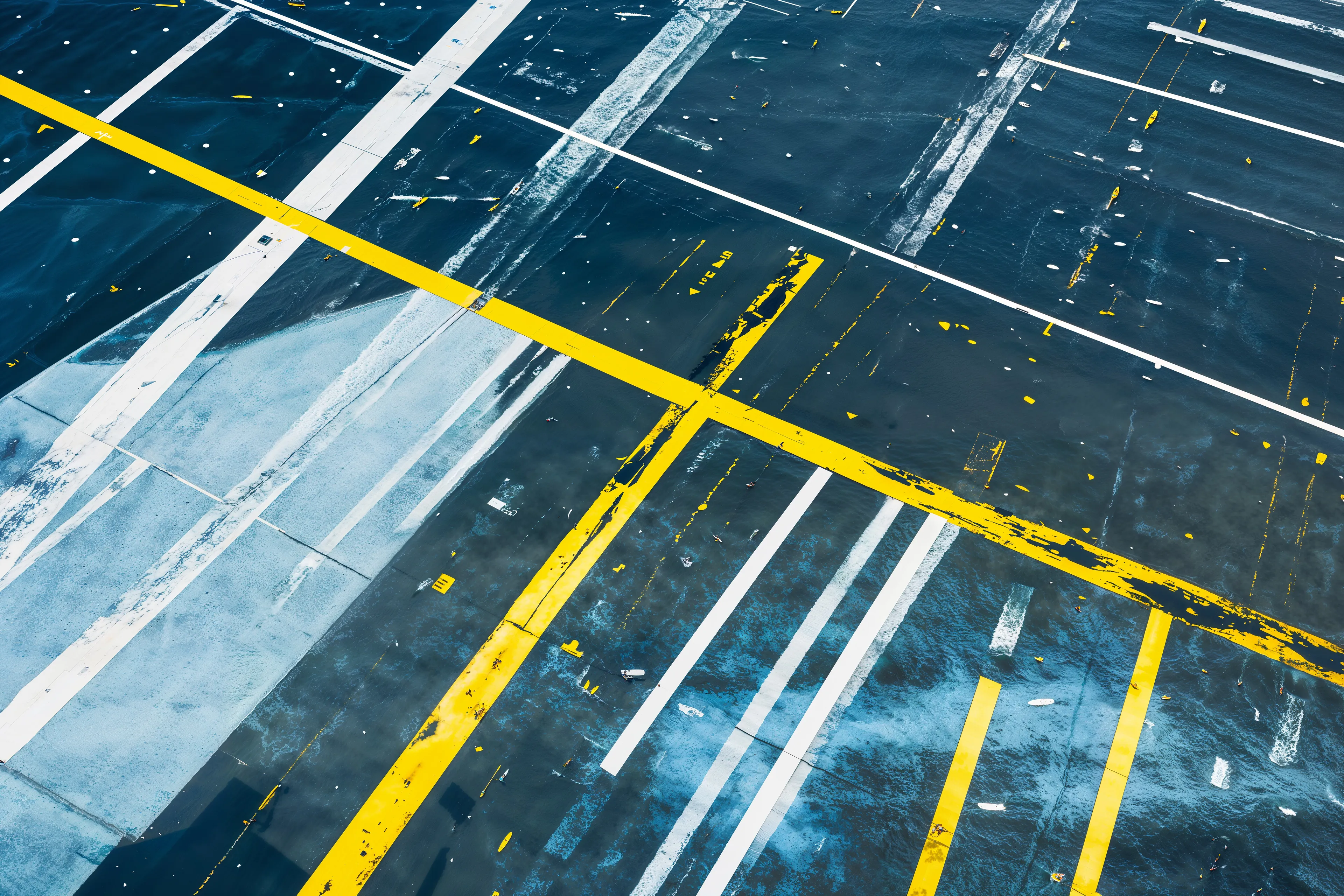

The absence of the cowboy shifts attention to what was there, but overlooked. Nature, enveloping and unencumbered, pushes forward from the background. The images reward a slower read, elevating the American landscape and the accumulated artifacts of the printed reproduction and digitization of these images.

This act of erasure extends a lineage of appropriation and intervention. Prince rephotographed ads to isolate the figure of the cowboy; Neff’s removal defuses that masculine iconography to engage a more universal language of the latent sublime. Like Paul Pfeiffer, whose erased athletes and crowds expose the systems and containers around them, Your Land asks viewers to consider what remains once the hero is gone.

The title itself points to the unstable ground of appropriation: who gets to claim an image, and whose land is it, yours or mine? The question echoes Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land, a song both celebratory and critical of American ideals. In this context, Your Land is a provocation about ownership, authorship, and the myths we inherit.

At stake is not only the American ideal, but our place in a transforming world where creativity itself is mediated by technology. What remains in Your Land is no less a human creation than those from the click of a shutter – existing simultaneously now as digital images and physical prints – textured from iteration, resistant to perfection, and layered in story just like us.

Releases