Taking Stock

Print / video details noted in each individual artwork. Each work has one Artist Proof associated with it, recorded as a separate but related series on Verse.

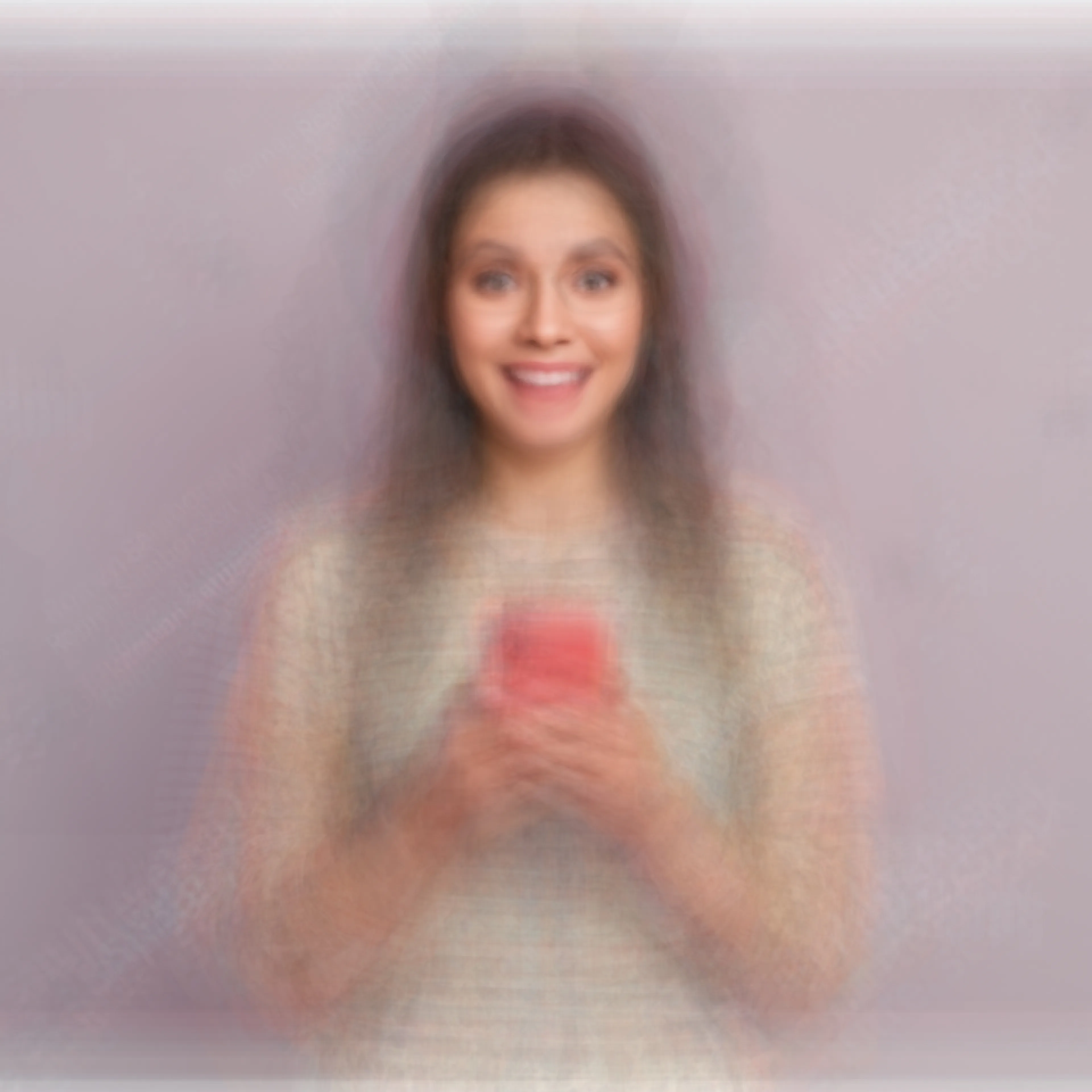

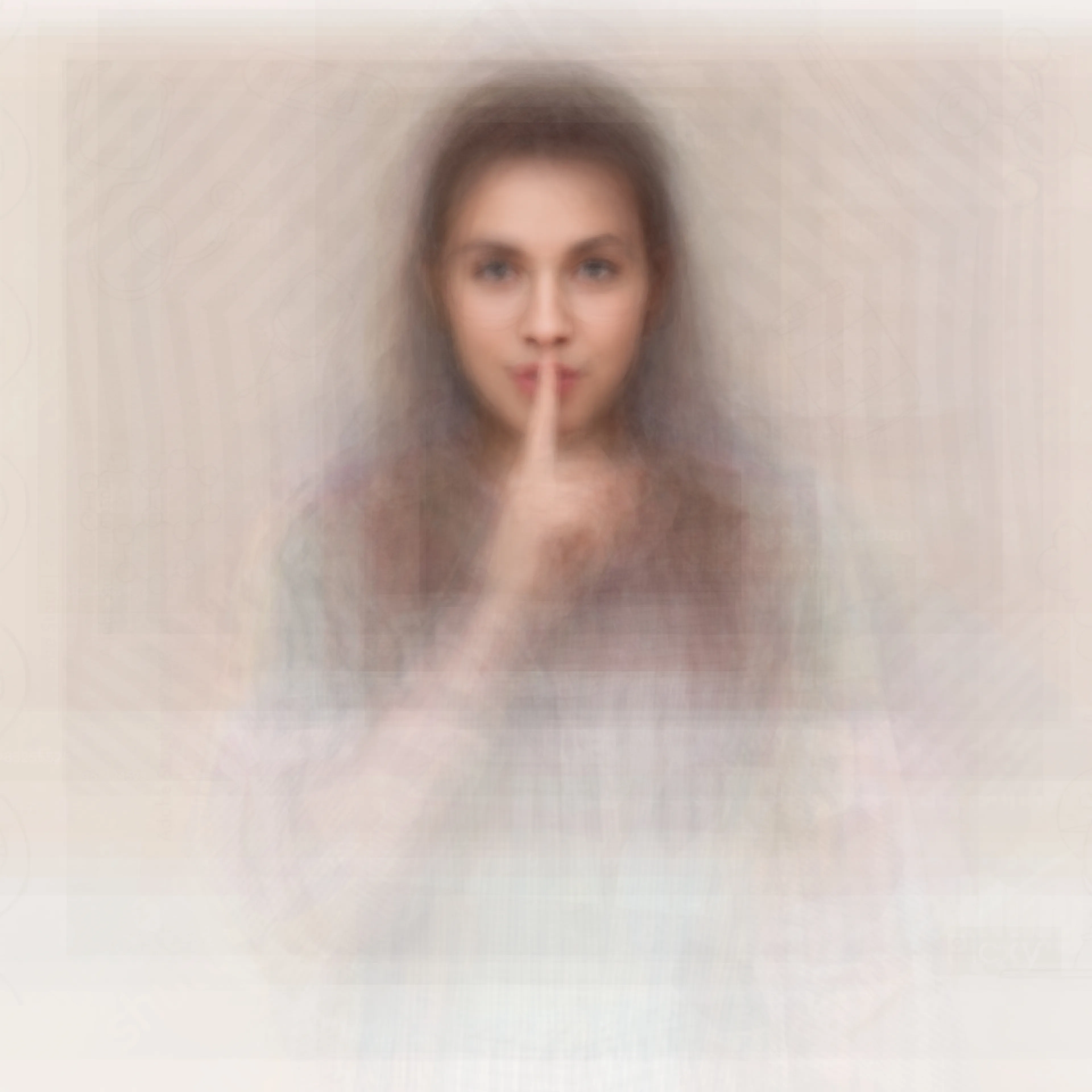

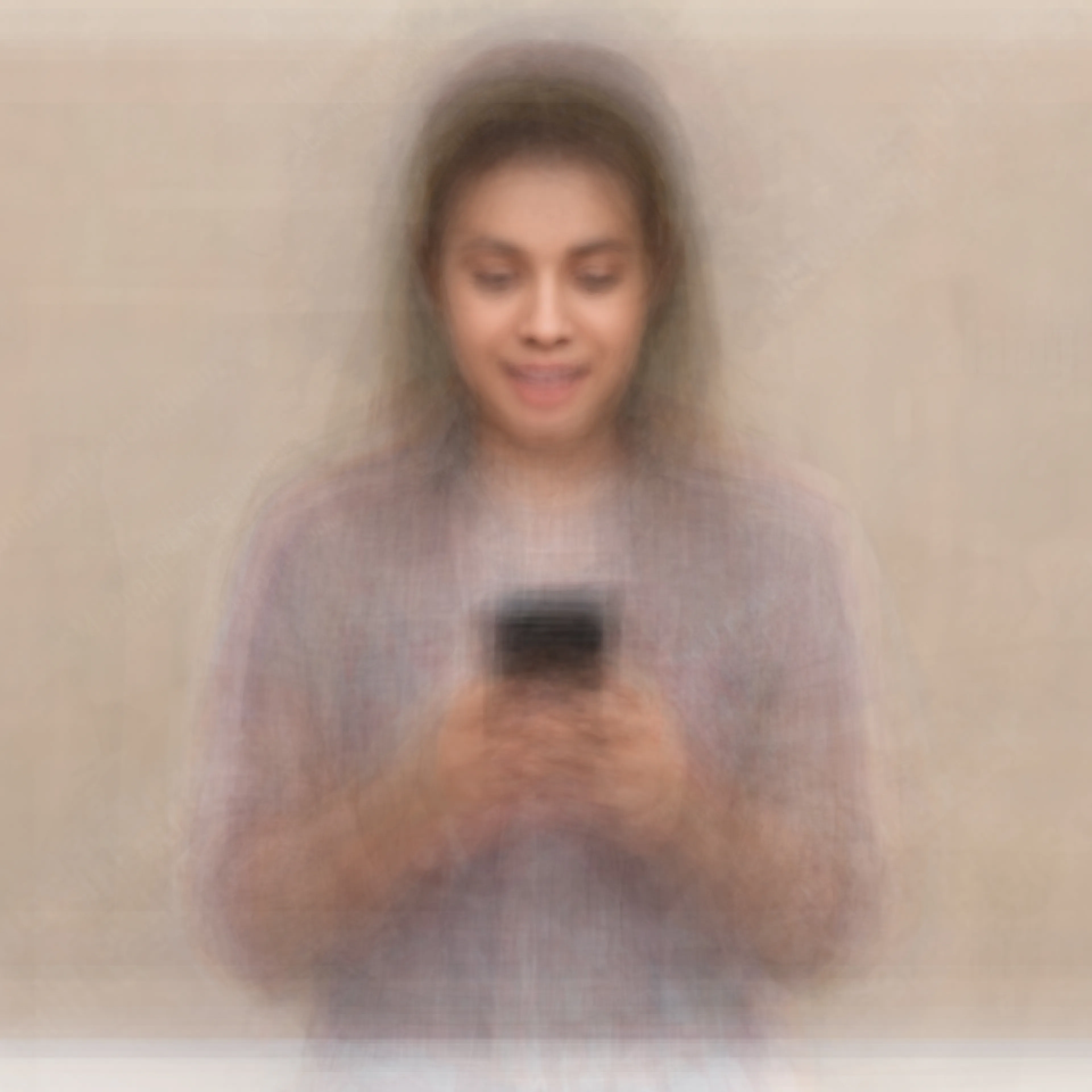

Michael Mandiberg has collected and analyzed 130 million stock photographs to create Taking Stock, a series of photographs and videos that surface the ideologies haunting these ubiquitous images.

Stock photos need to be more carefully considered because AI is learning from them. These generic photos saturate our visual landscape – instructing us through public service announcements, cajoling us to buy buy buy, and always attempting to pretend that gender is a stable binary. Unlike the way countless artists and scholars have dissected the influence of cinematic, fashion, advertising, and celebrity images, no decent photo theorist or historian will go anywhere near these photos. They smell too strongly of commerce and clichés. All studium, no punctum. This alone makes them worth considering, and now AI is analyzing these stock photographs as if they are factual evidence of what we look like – yet these images are far from neutral.

To start this project, Mandiberg wrote code that systematically downloaded every image (and its metadata) of an individual person on every stock photo website available. These include large sites like Shutterstock and Getty Images, midsize sites like India Picture Budget and Visual China Group, and small specialized sites like Afripics and Nappy. North American and European photographers create the vast majority of these images, with locations disproportionally in the Eastern European countries of the former Soviet Union. Ukraine and Belarus each alone has authored more than twice as many images than the United States; Russia and Serbia have each authored more than France, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined.

The populations of those ex-Soviet mega-producers are predominantly white, and the images they produce reflect that. Less than 10% of the images produced in those countries are tagged with ethnicities other than white/Caucasian/European. With the exception of Spain, the smaller portion of images that come from Western European countries are almost as homogeneous.

Mandiberg wrote machine learning code to analyze each of the 130,184,028 stock photographs collected for Taking Stock. The analysis first removed images of groups, and close-ups of hands and other parts of the body, leaving 75 million images of individual people. The code grouped these 75 million images in two different ways. A machine learning statistical model was used to identify topics or themes within the sets of keywords of these 75 million images, by determining which keywords tended to uniquely appear together. Each of these topics are represented by a long list of keywords. For example, words like "business," “corporate,” "executive," "success," "manager," "office," "suit," and "profession" tended to appear only with each other, and not with “finger,” "gesture," "point," "thumb", "show", "symbol", "hand", "sign" which formed a different topic. Because so many of the images are tagged as "happy" and "smiling" these words are statistically irrelevant. This analysis produced 64 different thematic topics, which are titled based on the first three keywords distinct to that topic. The largest topic is people described by the clothes they are wearing “shirt, clothes, jeans,” the second largest is “business, corporate, executive.” These topics reveal important contours: the third largest topic in the data is “finger, gesture, point” which are advertisement-bound images of people holding up blank cell phones, or pointing at empty space — an unnatural pose you likely have never performed. The fourth most common topic “fashion, beautiful, pose” is one of the series of topics about beauty where the subjects are disproportionately white women. When all the images tagged “beautiful” are white people, it is no wonder that the AI-based snapchat and tiktok beauty filters that are trained by these stock images, will lighten darker skin, and reshape facial features to be more European.

The code also finds the location of each figure’s face, body and hands, which it uses to group the images based on similarity in body position and hand gestures. Mandiberg made the selection for each artwork in this series from selections within this dataset, based on such groupings. For example, to make an image of a figure holding a phone, Mandiberg started with a selection of the 5 million images where the figure is looking directly at the camera, without rotating or tilting their face. From these, they then selected the 76,593 images in the “phone, mobile, cell, etc” thematic topic. Narrowing it further, they select the 5928 images where both of the hands are in the center of the model’s torso, and filter that set further to produce a cluster of 2618 images with the same hand gesture: holding a phone. The images and videos are assembled from these clusters. There are 5687 clusters that contain at least 100 stock photos, which is enough data to make a single print.

To make one Taking Stock print, the code merges the 64 images at the statistical center of one of these 5687 clusters. 64 images is enough to represent the much larger cluster when blended together, while not so many images that it loses the halos of individual layers, or blurs out the watermarks and edges of each image. To make the final print, a simple script recursively merges pairs of images, until all images have been merged. For the videos, each successive image is selected by the similarity between faces, finding multiple images of the same person, or at least the person in the cluster’s data that looks most like them – and creating some continuity between each rapidly sequenced image. The videos were also given a stereo score of murmuring AI voices reading the image descriptions.

It’s important to emphasize that these images and videos are not created with Generative AI. Rather they are constructed from the data used to train these generators, revealing the latent images already present in that dataset.

This work references long histories of photography, but it also does important work in the present. These works channel August Sander’s typological archive though Fancis Bacon’s horrific hall of mirrors, instantiating a kind of found-image Cindy Sherman. The videos are a chaotic cousin of Bill Viola’s slow/no motion video portraits, and Paul Pfeiffer’s basketball videos. The images conjure up spirit photography, via Jason Salavon or Trevor Paglen. The meaning is akin to Martha Rosler Reads Vogue, plus every issue of Men’s Health, Good Housekeeping, Vogue, Southern Living, and every other magazine published in the last thirty years. If Edward Steichen’s Family of Man represented global solidarity amidst the Cold War, this is what the family of man looks like through capitalism’s victorious lenses.

This work is deeply researched, and is research-based, but it is essential that these artworks not just present research in its original form. These artworks provide deep analytic insight, but do so through expressive means. The works present all the data in a transformed version of its original self. Mandiberg’s approach to making art juxtaposes data visualization’s goal of synthesizing information with art’s impulse to transform the everyday into moments of contemplation. This approach is articulated through a few key strategies: instead of synthesizing the data into conventional data visualization forms, they find a way to present all the data that gives it new meaning. They shift the context or scale of commonplace digital material to give it an affective dimension, allowing new meanings to emerge by creating feeling in the works. Often the last step is to bring digital information into physical space via historical or analog forms. The result of these approaches, combined in the creation of Taking Stock, is a series of works that creates a new sense of awareness, through its expression and poetics. This understanding of a long-standing problem of bias in the vernacular of consumer culture is now the basis for what AI is looking at, and how an even broader generation of image-making stands to continue these old stock perspectives.

—

Taking Stock

November 2024

All inquiries can be directed to curation@tender.art

Please note that 1 Artist Proof exists for each work in Taking Stock, recorded as a separate but related series on Verse and transferred to the artist.

Releases