William Mapan's 'Intimacy': A Verse Solos Panel

To celebrate the opening of William Mapan's Verse Solos exhibition, 'Intimacy', we hosted a panel discussion with William Mapan, our very own Leyla Fakhr, and two brilliant institutional panelists, Melanie Lenz (V&A) and Tamar Clarke-Brown (Serpentine Galleries).

LF: Good evening, everybody. Thank you so much for being here tonight. This is a very special evening for us here at Verse. It marks the fifth edition of Verse Solos, and we are honoured to be presenting none other than William Mapan, who has just arrived from Paris.

We feel incredibly fortunate. Tonight is particularly special because I’ve got a powerhouse panel with me—two exquisite and distinguished curators joining this conversation. Thank you both so much for being here and making the time.

On the far right, we have Tamar Clarke-Brown a London-based curator, artist, and writer. She curates and produces projects with technology teams at the Serpentine Galleries. Her work explores futurism, technologies, and diasporic practices. Tamar was named one of the Dazed 100 individuals in 2022. She has collaborated with numerous institutions including Autograph, ICA, South London Gallery, Tate, Yale School of Art, Somerset House, and many more.

Seated next to Tamar is Melanie Lenz, curator of digital art at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Melanie brings over 20 years of experience in curating, commissioning, and delivering creative projects. She specializes in digital art and culture and co-curated Chance and Control: Art in the Age of Computers, which ran from 2018 to 2019. Melanie has published extensively on early computer art in Latin America, gender and technology, and the collection and conservation of digital art. She is also one of the judges for this year's Lumen Prize.

As for William Mapan—I don’t think he needs much of an introduction. I suspect most of you are here tonight for William… and perhaps the wine. A great combination, William and wine. For those unfamiliar, William is an artist best known for his generative work, though he explores a wide range of mediums.

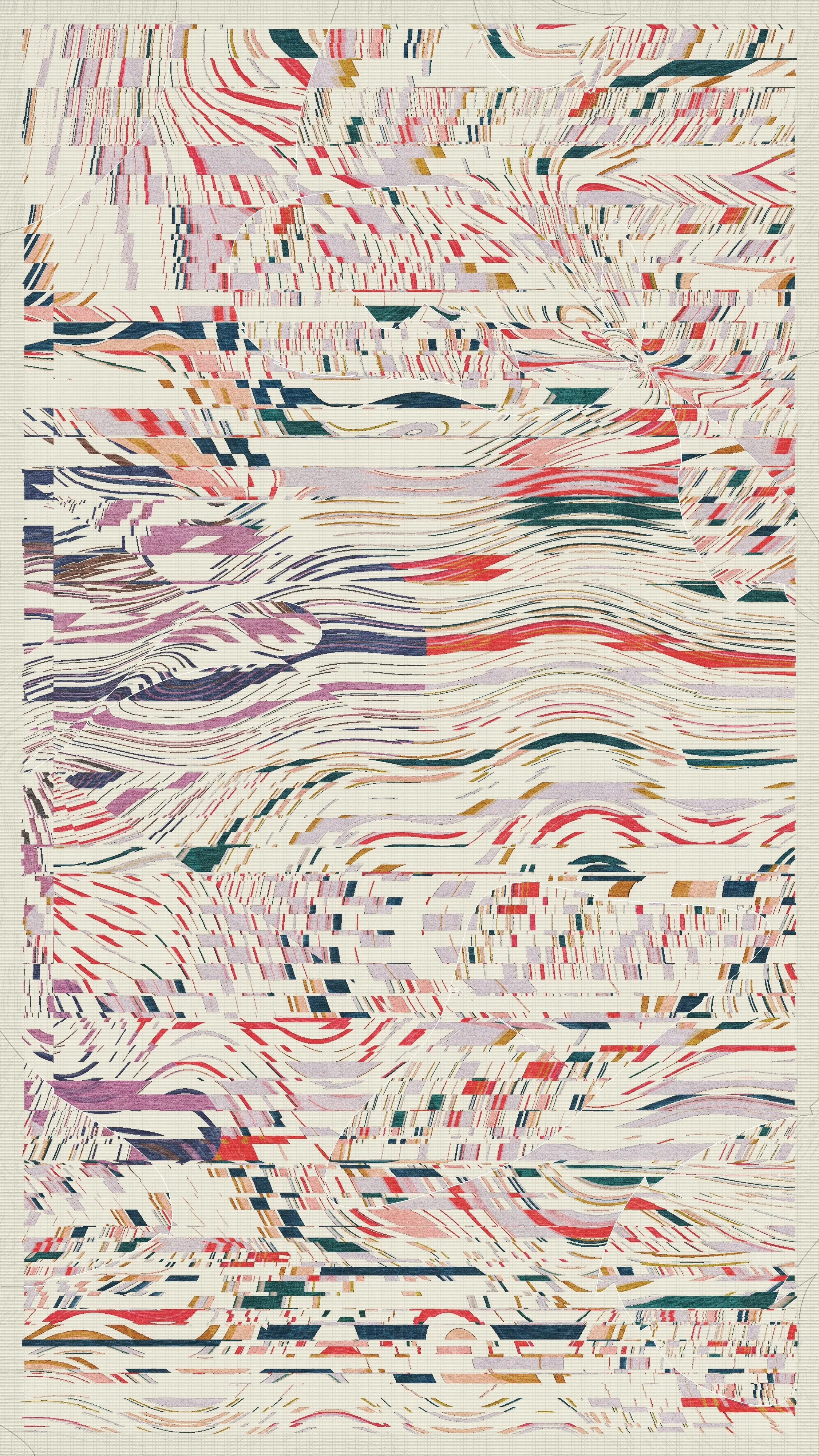

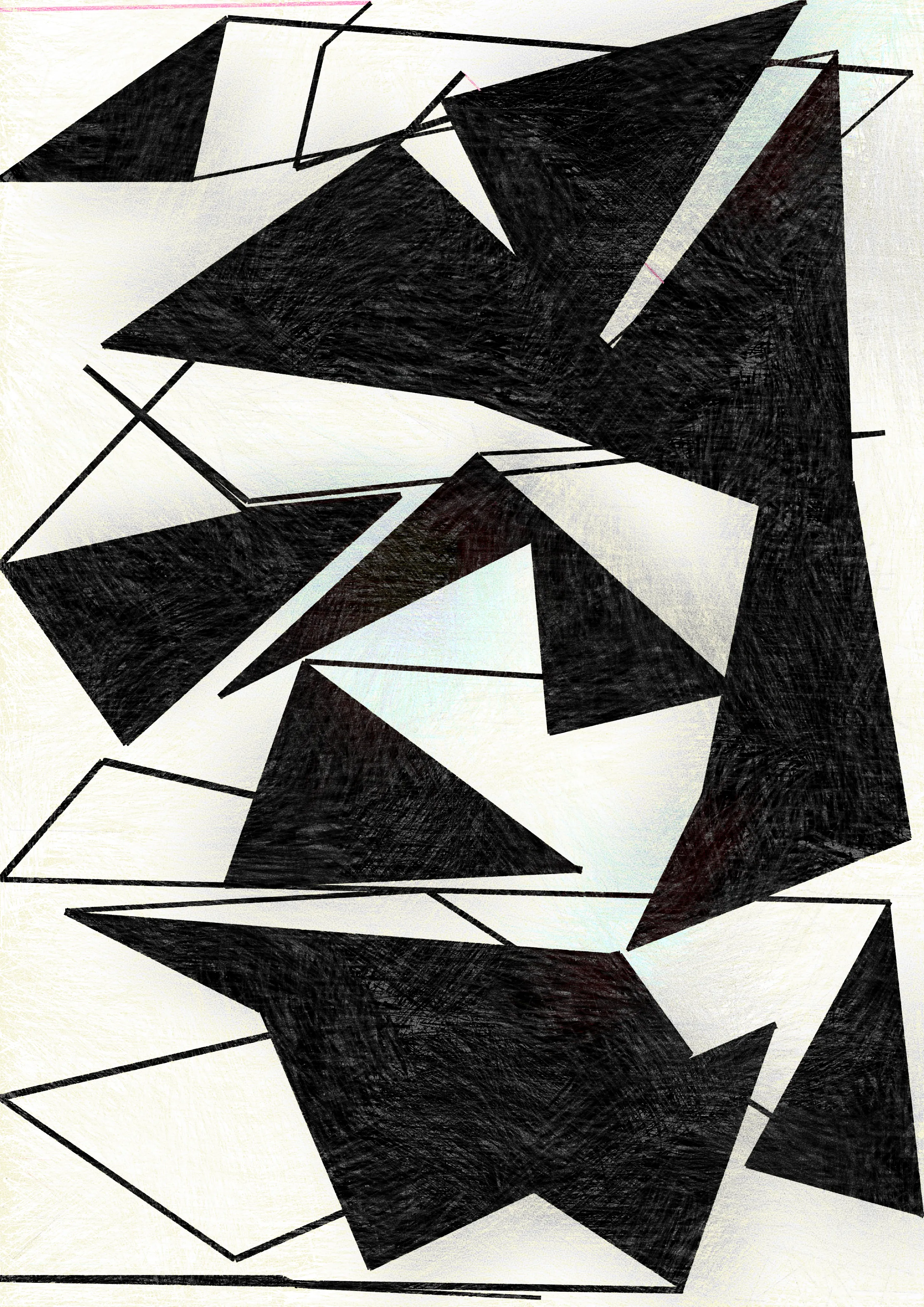

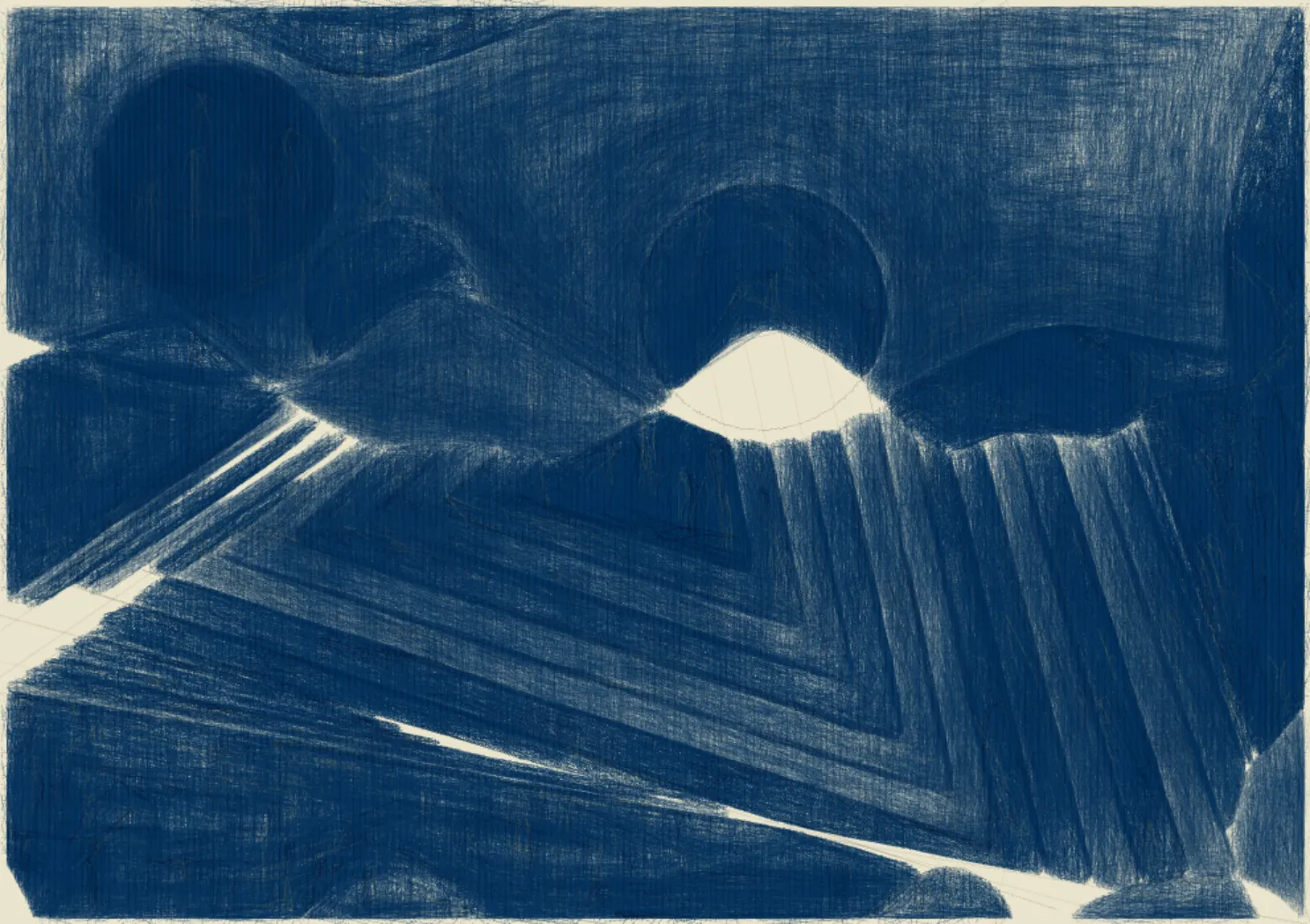

He’s recognized for series like Dragons, Anticyclone, and more recently, Strands of Solitude. But this evening feels particularly special as we are here for his newest series, part of this exhibition titled Intimacy. William, this body of work feels like such a departure for you. While texture and color have always been important in your work, this series feels like it’s reaching for something deeper. In a recent conversation, you mentioned you felt like you’d "cracked your own code"—that really stuck with me. Can you give us an overview of what the exhibition is about and the works it entails?

WM: Thank you all for coming. Hi—can you hear me? Intimacy—I just wanted you to get closer to me and to understand how I begin things: how I start ideas, how I initiate a piece of art. It often starts with my sketchbook, which is usually the foundation.

I wanted to create that sense of closeness, especially since I sketch a lot during my free time. Well, now it’s part of my full-time practice. I draw every day. It’s a way for me to express myself. So I thought—how can I expand that into something generative, into a system?

As humans, we’re all limited—our hands, our brains, our bodies. Creating a system allows me to go far beyond what I can do physically. I wanted to find a way to "crack my own code"—to figure out how I think using intuition. For months, I just filled my sketchbook with drawings, nonsense stuff. But I noticed patterns—where I would begin a shape, how I would start the next one, how my strokes moved.

And I thought, maybe I can translate this into code—build a system out of it. That’s how the Sketchbook Series was born. It’s been in progress for about 18 months now. It’s a deep dive into my own process, and I wanted to share that with you.

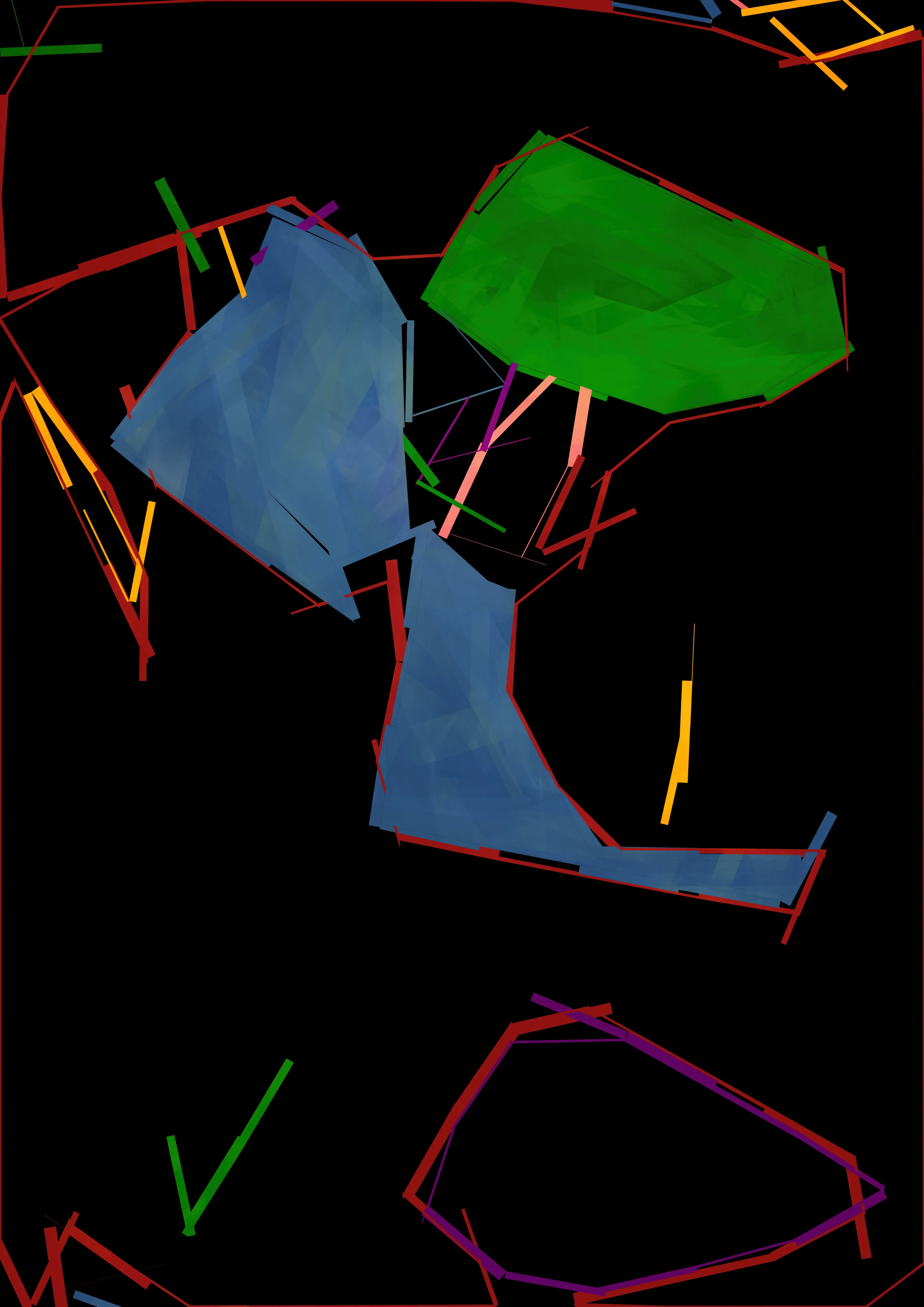

That’s why the show is called Intimacy—to bring people closer to me. There’s also another piece here titled Through Your Eyes. That one is about how I interpret what the algorithm "gives back" to me—like seeing the work through the eyes of the machine. It’s also a reflection on how the algorithm sees, how I see through it. Sometimes I’m surprised by what emerges—faces, expressions—and I’m fascinated by how the human brain recognizes features like eyes or a mouth in abstract forms.

For this series, I wanted to explore the opposite end of the spectrum from heavily textured or painterly work. I used digital brushstrokes, but still aimed to convey depth and emotion when seen from a distance. That’s the essence of what I was trying to express.

LF: What drove you to imitate the human hand so much in these works? That aspect feels very distinct from your previous work.

WM: I don’t think it’s about imitating the texture. It’s more about imitating how I place a line in my sketchbook. As I was telling some people earlier, it’s not about mimicking the appearance of a crayon or pencil. It’s about the gesture—the mood I’m in when I draw.

I analyzed myself a lot during the creation of this series. When I’m hungry or angry, how hard do I press the sketchbook? When I’m happy or tired, do I lift my wrist more? All those human elements—I wanted them to go into the algorithm.

That’s what people perceive as "crayon-like," but it’s really not about that. There’s no literal crayon tool in my code. It’s all variables and abstract concepts. What we’re seeing is how we, as humans, interpret it. What I’m doing is expressing myself and analyzing how I draw.

LF: That makes complete sense. Someone was asking me recently what I love most about this series, and I realized—it’s the soul it carries. That’s so hard to achieve with something generated algorithmically. Often, I feel stimulated conceptually by digital art, but it can feel emotionally flat. This series is doing the exact opposite—it holds emotion. I didn’t know you thought about all of this when creating it, but it definitely comes through.

Tamar and Melanie, as experts in the field, I’d love to hear how each of you responds to this series—and where you see it fitting into the wider contemporary art narrative. I know that institutional context is an important part of your work.

ML: My focus is on contemporary practice, but I work with a predominantly historic and early collection. So I’m very interested in the experimental spirit of early practitioners who tried to codify the act of drawing—starting with their own sketches and trying to turn that into code.

A lot of the works in the V&A collection explore computational aesthetics, which don’t necessarily have a gestural quality. But that’s not always the case. In fact, there’s really no single "digital aesthetic."

A piece that comes to mind is Vera Molnar’s Letters from my Mother. There’s another layer to it—intentional or not. I think it’s fascinating how contemporary artists like William embed something more than the generative process. There’s a human element that’s often overlooked in digital art, but it’s very present here. And that human aspect is crucial for contextualizing this work, even if the comparisons aren’t direct.

LF: That’s interesting. You mentioned earlier, William, that your work explores the relationship between human and computer. That dialogue seems to be a constant thread throughout history.

ML: Absolutely. If we look at someone like Harold Cohen—he spent his life working with one program, Aaron. He started as a painter, then transitioned into working with code. His relationship with Aaron evolved into a form of collaboration. These relationships between artists and machines can run very deep.

LF: Why do you think artists are so drawn to exploring their relationship with the machine?

ML: I’d defer to the artist on that one, but I’d say it’s an exploratory instinct—an urge to keep questioning. It’s probably different for everyone.

TCB: I think it’s about developing a relationship with computational practice. That history runs deep. One of the reasons I came into this field was to find intimacy within digital practice—within technology.

Increasingly, artists are not only exploring digital aesthetics but also the infrastructures themselves—interrogating what it means to become through and alongside these systems. Personal narratives are entering the space more and more, which really excites me.

Yes, we can talk about machines and systems, but at the end of the day, we’re still organisms. And the infrastructures we build shape our world. Artists are trying to trace their own expressive potential within the code, within systems they’ve set up themselves.

William spoke about cracking his own code—but I see it as also tracking your own movement. Ultimately, we’re all trying to crack our own codes—whether personal, societal, or systemic. That’s why these works resonate so deeply. They’re tactile, they’re human. That’s what excites me about this space, and William’s practice within it.

LF: Yeah, it's interesting that you picked up on that, Tamar, because that's exactly what you were saying earlier—that this series of work is almost like journaling for you, and that you want people to go on that journey with you. You used a really nice phrase about tracking how your line and drawing evolve, so it's nice that that has come together.

I think we're at a really interesting point right now, where there’s so much more awareness and conversation around digital art. There's a lot more movement in that space. William is still relatively early in his artistic career, and we’re excited to have him here—he’s grown very quickly.

Even though there's increasing attention on digital art, it still feels like there's a separation between artists working with digital mediums and those working in more traditional ones. I’m curious to hear from you, Tamar, because the Serpentine runs two programs. On one hand, you’re working with artists who are already represented by galleries and museums and giving them incredible exhibitions. On the other hand, you’re working on the Arts and Technology program. Do you feel like your audiences for these two areas are different? Do they overlap? Is there a different kind of interest in them?

TCB: A couple of years ago, we restructured the Serpentine a bit to focus on key areas we wanted to prioritize moving forward: civic practice, technologies, and ecologies. Those are the main pillars.

The Arts Technologies program is unique because we operate within a traditional arts institution. The Serpentine has always been known for asking artists about their unrealized projects, and we've been trained to think about the impossible as a commissioning institution.

In Arts Technologies, we’re in a unique position—we’re tasked with exploring how artists working with technology are shifting the broader art ecosystem. We’ve released a publication series called Future Art Ecosystems, currently on its third edition, with the fourth coming next year. Each edition includes interviews with practitioners in the space.

The first volume focused on what practitioners working with technology need—teams, IP, better legal structures. The second looked at art in the metaverse and gaming. The third focused on art and decentralized technologies.

Through these publications, the wider institution has started paying attention to how we can adopt and implement these learnings. For instance, we coined the term "UX of art"—looking at how audiences interact with art and how that can shape future directions. Whether that’s creating a Twitch channel where artists and audiences engage in real-time conversation or building a video game exhibition that allows users to mint Web3 tokens, we’re interested in deepening that relationship.

Ultimately, as an artist-led institution, we want artists to guide these conversations, especially when it comes to civic and social practice through technology.

LF: Yeah, I think you’re quite unusual in that sense—and it's great. You were saying that this approach draws a lot of young audiences. But traditionally, Melanie, digital artists have often been on the periphery of the mainstream art world. Why do you think that is? Why has there been this sense of exclusion for those working with technology?

ML: Early digital art practitioners were often stigmatized because computers were associated with militaristic and industrial origins. Artists like Manfred Mohr recall being attacked people threw eggs at him, accusing him of destroying art by using machines that had been used for war.

There’s always been a divide: some people believe technology will save us, others think it’ll destroy us. That anxiety has permeated culture. In the early days, computers were associated with labs or industry, not personal use, and that made them intimidating.

In popular culture and science fiction, computers were often depicted as scary, non-human entities. That bled into the critical reception of early digital art—it was seen as cold, impersonal.

There's also this romantic idea of the human hand in art—the notion of the "individual genius." When you introduce algorithms, you get into questions of control, creative authority, and authenticity. These are still questioning that contemporary digital artist face.

Interestingly, even though these artists operated outside of traditional art institutions, communities still formed. They didn’t exist in a vacuum—they were responding to movements like constructivism and abstract expressionism. These communities thrived on the periphery.

My question back to you is: how important is institutional acceptance? These communities existed and thrived without it. Does institutional recognition validate the work, or does it risk creating unnecessary hierarchies? Personally, I work within an institution, and I do think it's important to engage with contemporary practitioners. But I question whether creating hierarchies is useful—both sides can coexist.

LF: That’s a good question. I think it is important because institutions are responsible for recording art history. That process is subjective, of course, and institutions have historically made mistakes—like a lack of diversity and representation.

Still, if nothing is recorded institutionally and everything is left to market forces or informal networks, how can future generations learn from past practices? That’s why I personally feel it’s important. I worked independently for a long time, but I joined Verse because I became excited about the digital art space. For me, the anchor is art history—it’s how I make sense of everything.

So, in follow-up to your question: how important is art history when it comes to placing or narrating an artist's work today?

ML: I’ll jump in. I think art history is important—not necessarily in terms of influence, because many new practitioners aren’t aware of what’s come before. But awareness of historical context can only enrich and deepen your practice. You can lean into it or push against it. Of course, culturally and technologically, we’ve moved forward a lot in the past 60 years, so perspectives shift. I'm definitely biased, but I do think it's critically. William, I’d love to hear your take on this.

LF: Yeah, William—you’ve found success very quickly. How important is it to you to be recognized by institutions? Does that matter to you?

WM: I think it does matter that institutions recognize my work. I want my work to be part of art history someday.

We learn art history through books and the internet, and museums and galleries shape culture. Subcultures usually stay subcultures until they're brought into the mainstream. For me, it’s important to be in those spaces, but that’s not my end goal.

I want to be forward-thinking—not just someone doing what others have done. But to move forward, I need to know what came before, and that knowledge often comes from institutions.

I always say I want my son or grandson to one day say, “Yeah, William was doing this in 2022,” and have that moment recorded—maybe on the blockchain. I want to leave a trace. That’s the goal for any artist: to express yourself and be heard. Institutions help with that.

TCB: But a lot of your early support came from online communities, right?

WM: Yes, my first support came from online communities. But that doesn’t mean I have to stay there. It’s a bubble—and I don’t like bubbles. I break bubbles. If a group of people doesn’t know me, I’ll go to them.

ML: Do you think that’s part of breaking down the separation? Would you define yourself as a digital artist, or just an artist?

WM: Just an artist. What does “digital artist” even mean? Are you defined by the tools you use? For me, no. You just want to express yourself. The tools don’t matter. “Digital” or “traditional” doesn’t make sense—we’re all just artists. I really don’t like that label at all.

ML: But then that's—to answer your question—why they’ve been separate. But perhaps the idea is that they become one, and we stop making a distinction like, "Why isn’t it being accepted by the art world?" We should think of it as artists creating works in different ways, about different things.

WM: I also think there’s a huge historical burden. Previously, there were fixed definitions—rules to follow. And if you wanted to fit in but didn’t follow those rules, you were considered an outsider. People would say, “Because you’re not using oil paint, it’s not art.” And you'd be standing there like, “No, it is.” There’s always been a distinction—a friction—between digital and traditional. But there really shouldn’t be.

TCB: I think it's the same. Increasingly, artists are doing just that—blurring the lines. They’ll even resubmit their bios and say, “Can you just take ‘digital’ out of it?” Even though that was the bio we originally worked with. It’s like many artists want to break out of these categories and say, “I’m a multifaceted person. Sometimes I work with this, sometimes with that. But I express myself in different ways.” I think the comfort level has gone up too. That’s thanks, in part, to people like Melanie who’ve built those bridges and helped the traditional art world feel more at ease. Now, hopefully, the rules are coming down, which opens up more opportunities. On the digital side, we can broker relationships or bring certain things to the table—like collaborations with software companies, for example. On the more traditional side—I hate using that word, it's really hard to find a better one—but the point is, it’s exciting when walls come down.

LF: Yeah, I agree. I agree with William. Whenever we have team meetings, I don’t like calling people “digital artists.” I just think: an artist is an artist. If I’m excited about an artist, I’m just excited. They might work across various mediums. What’s become difficult, though—and I’ve noticed this—is how to contextualize artists who’ve gained attention primarily in the digital space. That’s harder to track. You mentioned tracing earlier—I find it tricky. I’m actually curious to hear from you, Tamar. Traditionally, when working with museums or institutions, we track where the artist has exhibited. It’s quite linear. But with someone like Gabriel Masan, things have changed. How do we look at art now? That’s a big reason I joined Verse—my kids didn’t want to go to museums anymore. They’re absorbing culture through their phones and laptops. So how has that shift changed things?

TCB: One part of it is definitely the breaking down of walls. Online communities are helping us see who’s inspiring who. Artists are really supporting each other in unique ways—saying things like, “Have you seen this person’s work?” That kind of encouragement is powerful. It lets people share experiences—what it was like working with someone, what ideas emerged, what collaboration looked like. Hopefully, that visibility helps more artists get support. At one point, it felt overwhelming—and it still can—but it’s also exciting. The goal now is to create infrastructure—exhibitions or educational programs—that foster development and growth. Whether it’s through schooling, teaching, or sharing tools and critique, we’re building a growing community. I still do traditional studio visits, but now there’s this expanded awareness that so much more is out there.

LF: Melanie, what about you?

ML: That’s something we’re constantly grappling with—how to engage effectively with different artists and audiences, and how to stay current and relevant. We also have a historical collection that we need to maintain—it’s a permanent collection, which makes it different from commissions or other forms of engagement. The way we approach this is by working collaboratively. It’s not just one person with one idea; we reflect multiple perspectives on who we work with and where we look. There’s still so much more to do, and we don’t have all the answers—but at least we’re conscious of it.

LF: William, you mentioned earlier that you grew up going to museums—that informed a lot of your practice. You’ve seen physical exhibitions. But now, especially after joining Twitter and Verse, how important is that physical experience to you? How do you feel about viewing art on a phone versus in person? Do you try to balance the two?

LF: You’re pretty good about it actually. You don’t obsess.

WM: I think what matters the native medium of the artwork is. If a piece was made to be shown on physical walls, you should go see it in person. If it was created for digital consumption, then experience it digitally. It’s really about respecting the native medium. I don’t think it’s complicated—just listen to the artist. What was the message? What was the artist trying to express?

LF: You say it’s a simple question, but putting together this exhibition was really hard. People assume, “Oh, you just put some pictures up.” But for me, working in digital now makes it tougher. My first impressions of the work are on a laptop or phone. I was saying this earlier to Tamar and Melanie—that as a curator, you’re used to being physically around the work. You feel how it changes the room. That physicality gets lost when you're seeing things in just one format. Now I have the responsibility of turning that into an exhibition that really does justice to the work—and shares it with a wider audience. I’d love to hear from both of you, especially since you often display your permanent collection.

ML: Sadly, we don’t display it that often—but currently, some work is on view. So yes, a little plug: check out the patch print! We’re thinking about digital resolution in prints. A lot of our digital works are on paper, which is an interesting intersection. Digital print might sound antiquated, but it still offers artists an outlet—one that isn’t always possible on screen. I don’t see it as a contradiction, and I’m not saying one medium is better than another. There’s room for both. We work with a lot of works on paper as well as other ways of encountering digital art.

WM: But I agree—when the piece changes medium, it becomes tricky. It’s no longer in its native format. These particular pieces were made for print, so that transition was easier. But when it’s a digital-native piece, it’s harder to translate. You lose information—just like you do when you photograph a painting. It goes both ways. Anytime you shift medium, that’s when the hard part starts.

LF: And people come in with preconceptions. One visitor said they imagined some works were small and others large—just based on what they saw online. Everyone has their own imagination. Tamar, you work on some complex digital installations. How does that process work?

TCB: It reminds me of a funny moment—we were building a game for an exhibition, and I kept asking Gabriel to sketch something—just sketch what was in their head. They absolutely hated it. They wouldn’t draw at all—just went straight to Blender. I’d say, “Here’s a pencil,” and they’d say, “Nope.” That medium wasn’t right for them. Their mind went straight to sculpting digitally.

That was a big challenge: translating something created in a digital-native way into a physical space. In a game world—like the one we built in Unreal Engine—the physics are completely different. But now, we’re getting excited about mixed reality. Working with digital technologies, what new possibilities emerge when your body is in the space?

Exhibitions are physical—you are a body in a space. What does that mean for how you experience art? Increasingly, we’re asking that. And intimacy is key—your body has a relationship with the artwork. With digital pieces, that changes depending on the format.

When we translated the game, we wanted different ways to play. Gabriel is interested in texture and archiving it. So we made the space tactile—furry gaming chairs, changing light and sound. You feel a jolt when you enter—like you’re stepping into a space of change and growth. They really wanted to leverage the fact that you're a body in a space.

That’s something I’m excited about. Artists like Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley—she focuses on what it means for someone to register their presence alongside the artwork. How does that presence shift the experience?

LF: Cool. Well, before I open the floor to the audience, where the real questions begin—what’s next for you, William?

WM: Less work—and more physical. I’ve spent years sharpening my digital skills. I don’t know everything about code, but I know I could teach myself. With physical media, though, I’m way behind. If I want to keep evolving, I need to build up my physical practice. So I think next year will be more physical for me.

LF: And you’re quite disciplined. You practice every day—you sketch, you paint.

WM: I just don’t show people photos. Yeah, I practice. Believe me, I’m there every morning, but it takes time. Any practice takes time. I’ve spent 12 years coding and only four or five painting, so there’s a gap between the two.

LF: I feel like that’s what you’re doing with this series as well. They’re really overlapping, and you spoke about this earlier — how your physical practice, using the brush and the pen, influences how you code, especially in your digital work. I think it’s evolving very nicely. I love how dedicated you are, doing it every day, and I’m excited to see where you take it. Do you do it because you like to lose yourself in it? You said you’re just doing it to get better, but I feel like you also enjoy getting lost in it. Whenever I ask you a question, you’re like, “Let me go painting. I’ll get back to you after I finish.” So is that part of it too?

WM: I feel like the digital space is moving too fast, and for me, painting is a way to slow everything down. I don’t even have internet in my studio. I made that choice. That’s why I don’t answer your messages. But for me, it’s a safe space. My thoughts are my own. Even my body is turned toward something I’m making with my hands. It feels different. I want to explore that. And I also want to bring what I know from software, from computation and algorithms, into my physical work — see what happens when I go the other way around. Yeah, maybe I’ll break my wrist, but I want to explore that too.

LF: Right. What’s next for you, Melanie, in terms of expanding the collection or looking at more digital art? What’s happening at the V&A? What should we look out for?

ML: So I’m currently co-editing a book about histories and contemporary practices across different geographic locations, involving artists both within and outside of the collection. That’s consuming most of my headspace at the moment.

In terms of the collection, we’re consolidating what we have, identifying gaps, filling those gaps, and continually thinking about what it means to collect contemporary work.

TCB: We also have a conference coming up called Cultures of Ownership. As part of what we do, we look at different ownership structures emerging from artists working with technologies or alternative infrastructures. That’s coming up in November and will bring together a lot of research and practitioners in the space. For me personally, I’m about to start working on some new commissions.

LF: Exciting. Well, thank you all so much for joining us this evening. I’m very grateful. I’d love to open up the floor for questions.

Audience Member: I have a slightly contrary point to what you all were discussing. I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

I actually think it’s important to highlight that this is a digital art collection. The reason I say that is because I believe digital artists go through unique challenges, and if we don’t highlight that, we’re not educating the public. It’s the same as when we talk about diversity — like Asian or Middle Eastern representation. It’s important to highlight that because these systems are still controlled by rigid structures.

Don’t you think sometimes it’s necessary to emphasize these aspects so that, one day, artists can simply be recognized as artists?

ML: Yeah, I think that’s important, but not to the point where it becomes restrictive. It should be used with an understanding of the breadth of what “digital” can mean — not defined in one rigid way.

When we talk about digital, it encompasses many things. And yes, terminology changes constantly. I usually add a caveat when I say I’m a curator of digital art — to clarify what I understand “digital” to mean.

So yes, I think it’s important to acknowledge it at this stage, but also to recognize that it doesn’t mean one mode of working or thinking. Some artists don’t want to be labelled that way, and we should respect that too.

TCB: I think from an institutional perspective, it’s about asking: “What do you need? What do you want? How can we support your practice?” We need to have those conversations and document them — to inform reports and spaces like this.

Yes, we need to pay attention to these issues and do our due diligence, until the labels come down. But artists also have the right to say, “I don’t want to be boxed in.” As curators — the word comes from Latin meaning “to care” — that’s at the heart of what we do. If we don’t understand artists’ needs, we can’t move the field forward.

Audience Member: I’d love to hear from all four of you about process. Often it’s hard for general audiences to understand the technical skill involved in digital art. Should we be talking more about artists’ methods? Is it important to communicate this at the institutional or dealer level?

LF: We talk about this a lot on our team, and honestly, opinions are divided.

As an artist, it’s not about technical ability for me. I might intuitively recognize something as technically well done — like I would with a painting — but that’s not what interests me most.

Of course William is an incredible coder, and yes, that’s important. But it’s not the first thing I look at. I look more holistically at the artist — what are they trying to do, where are they going, what’s the arc of their journey? That’s exciting.

ML: Yeah. Not speaking for the V&A, but the V&A is a museum of process. We’re very interested in how things are made. That said, we still weigh the output heavily. With generative art, for instance, there’s a focus on seriality and outputs.

I think it’s important for curators to understand and share how the work is made — but not necessarily give it equal prominence. It’s not about giving a step-by-step lesson. Still, understanding the material, skills, and processes behind the work enhances appreciation.

TCB: I think it depends on your goals. At Arts Tech, one of our big focuses is advanced production. When we made a game, we brought production in-house.

We worked on it daily with the artists. It was important to understand workflows — how animators talk to developers, what happens when assets are handed over, etc.

Knowing how something is made lets us advocate for funding or longer timelines.

Many of us come from artistic, legal, or design backgrounds. We want to be in the process. At Serpentine, our producers are equal to curators — they have to be. We can’t operate without them. We’re artist-led, so we need to understand the process to support and optimize it.

LF: I want to follow up — of course I need to know the process, but I don’t know the process. It’s not make-or-break for me. Other things interest me more than technicality.

ML: I’d add — there are different levels of knowledge. If we acquire a work, we need to know how it’s made for conservation purposes. When it comes to public interpretation, we might not show the code. We debated this when we acquired a Casey Reas work in 2010 — should we display the code? I won that argument. It’s interesting to reflect on that now.

LF: Did you display it?

ML: Oh yeah. It’s on permanent display. But the label is in English — not code — and displayed alongside the work. So yeah, I think different layers of information are needed. It’s crucial to understand how a work is made, but how and with whom you communicate that information varies.

WM: From my side, I’m trying to make things that can be read by many people. I want to have all types of conversations — not just one. Yes, process is important, especially in art. But sometimes there’s too much emphasis on how it’s made — like, it used this crazy computer or advanced tech.

But that’s not always the point. With generative art especially, we should ask — is this a subset, a sub-movement, or part of art as a whole? For me, digital art is a language. The algorithm isn’t the end; it’s how I deliver the message. So yes, process matters, but the real question is — did I say what I wanted to say?

TCB: Public responsibility plays a part too. We’ve worked to show more of the backend. During the recent tech boom, even our own organization struggled to grasp what we were doing — publications, events, etc. So, we had to help the organization — and our audiences — understand how to enter the space. From an institutional standpoint, we have a duty to onboard people and steward them into this world.

LF: But my counterargument is that focusing too much on process can alienate audiences. I just respond to the work itself. It’s an interesting conversation because yes, it’s integral — but we don’t obsess over painters’ processes in the same way. Maybe we should, but generally we don’t.

WM: I like to think about it like dancing or singing. The first thing you feel isn’t the process — it’s the emotion, the message. When something is so good, you say, “Wow,” and then you dig into how it was made.

LF: That’s usually what happens. Any more questions?

Audience Member: William, you spoke about your physical and digital practices. Historically, people like Harold Cohen with AARON refined the algorithm, but it didn’t feel complete until he inserted himself. Do you feel that way? You described the algorithm as your child — and with children, you want to correct them, but sometimes you shouldn’t. Does that create a feedback loop where you go back and refine the algorithm?

WM: Definitely. As adults, we lose creativity and freedom. I have a two-year-old, and I give him crayons and say, “Do your thing.” And he does — it’s amazing. Humans are intuitively creative. I’m trying to find that again. That’s why I move between physical and code — to break free from what I was told was good or not good. My relationship with my physical practice is very basic. The base — the plate — is me. Those marks are part of me, but I’m trying to dig deeper, to find what’s underneath.

William Mapan

William Mapan is an artist based in Paris who has garnered significant international attention for his generative practice. With a background in software development and visual art, he combines computer science with his passion for pigment, light and texture. He is known for his ability to replicate the materiality of physical materials in his work, transforming the digital canvas into a textured...

Leyla Fakhr

Leyla Fakhr is Artistic Director at Verse. After working at the Tate for 8 years, she worked as an independent curator and producer across various projects internationally. During her time at Tate she was part of the acquisition team and worked on a number of collection displays including John Akomfrah, ‘The Unfinished Conversation’ and ‘Migrations, Journeys into British Art’.

She is the editor...

Tamar Clarke-Brown

Tamar Clarke-Brown is a London based curator, artist and writer. Currently producing and curating projects with the Arts Technologies team at Serpentine, her interdisciplinary work centres around experimental futurisms, technologies and diasporic practices.

Tamar's work involves commissioning new artworks, events, research and R&D projects engaged with experimental worldbuilding and exploring...

Melanie Lenz

Melanie Lenz is the curator of Digital Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Based in London, she has over 20 years’ experience of curating, commissioning, and delivering creative projects. Specialising in digital arts and culture, Melanie co-curated Chance and Control: Art in the Age of Computers (2018-2019) and has published papers on early computer art in Latin America, gender and technology...

Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.