Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

William Mapan in conversation with Peter Bauman, Julia Greenway, and Leyla Fakhr

LF: This is quite an exciting moment, and we’re grateful you’re here. My name is Leyla Fakhr. I’m the Artistic Director at Verse, and one of our most important initiatives is the SOLOS program.

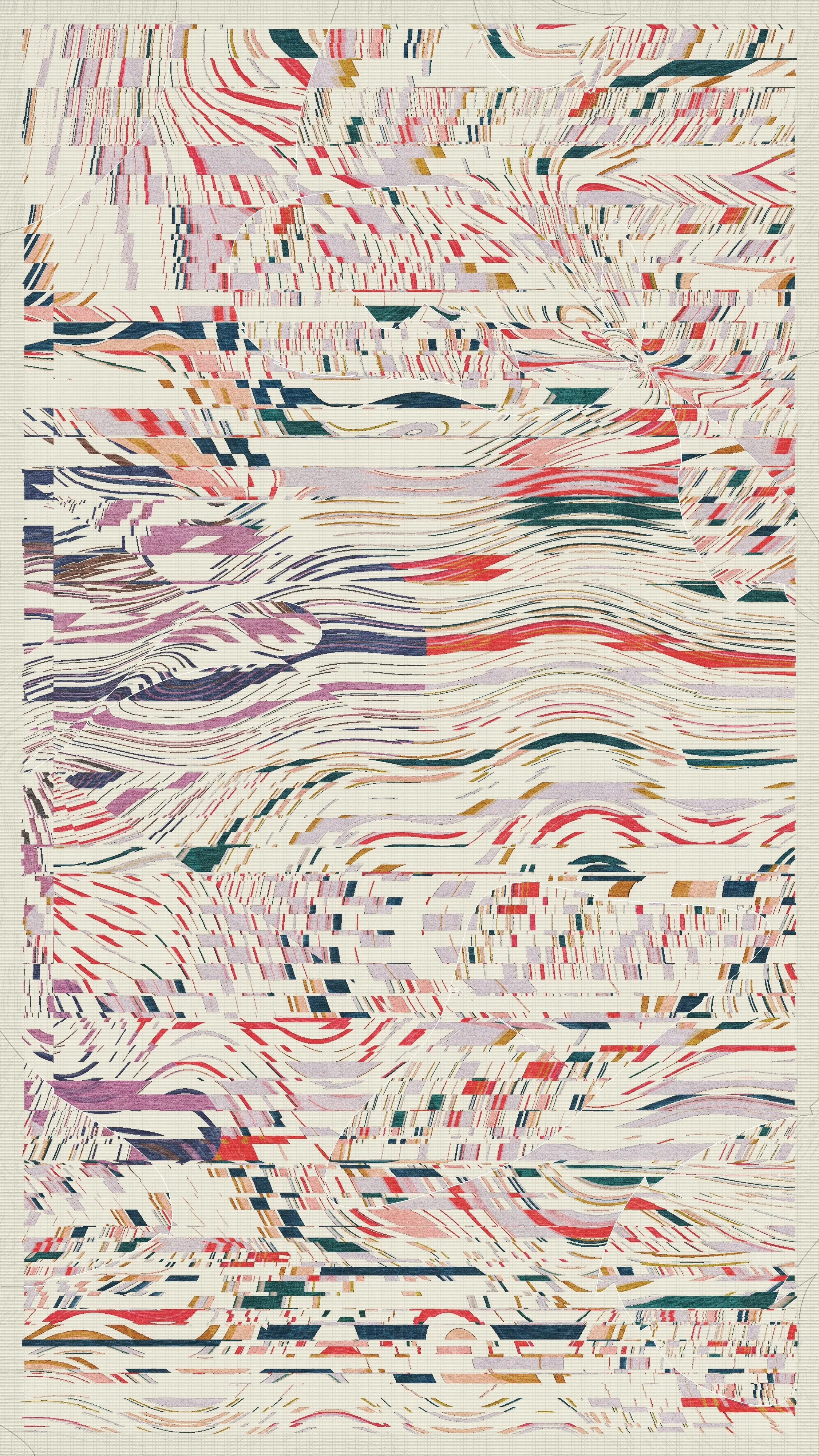

SOLOS is a gallery platform where we work with artists who use the digital medium not just as a tool, but as a way of thinking. I honestly can’t think of an artist who represents that more than the one we’re celebrating tonight—William Mapan. So thank you, William, for being here.

It’s been incredibly inspiring working with him—not just on this exhibition, but also on our last one in London in October 2023. That show was called Intimacy. This one is called Extension, and it’s a continuation of a body of work William began exploring back in 2022.

When we first started talking William, you said you were thinking about these concepts—and you wanted to title this exhibition Extension because you see the digital medium, specifically code, as an extension of yourself. Can you tell us more about that, especially in the context of what we’re seeing here in this exhibition?

WM: Yeah, I can definitely explain—depending on how much time you have! I’ve been in my studio sketching and painting a lot since Sketchbook B was released. I spent a lot of time locked in the studio, trying to understand myself—who I am as an artist, a painter, a generative artist. What do all these practices mean to me? What’s the role of the computer in all of this?

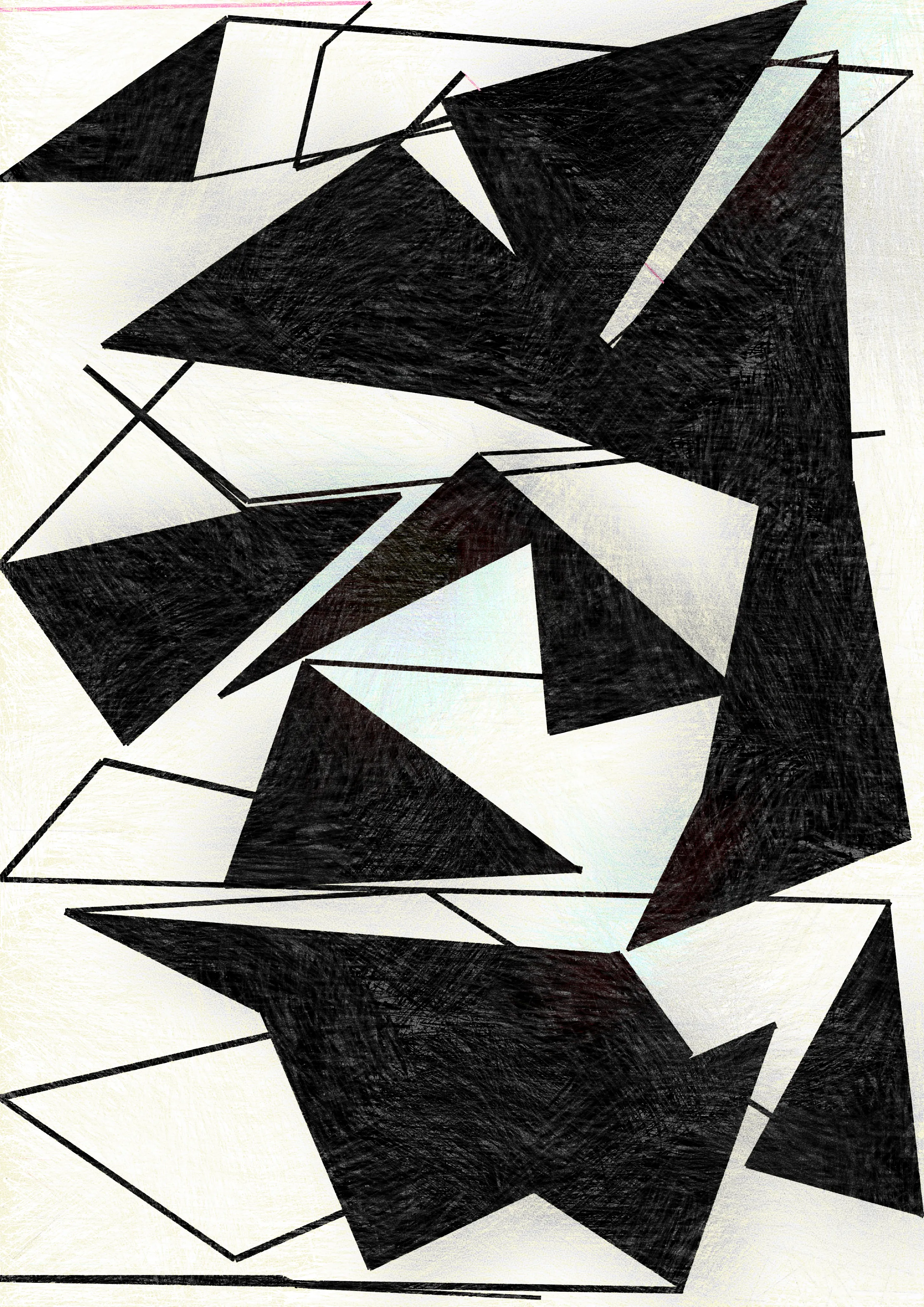

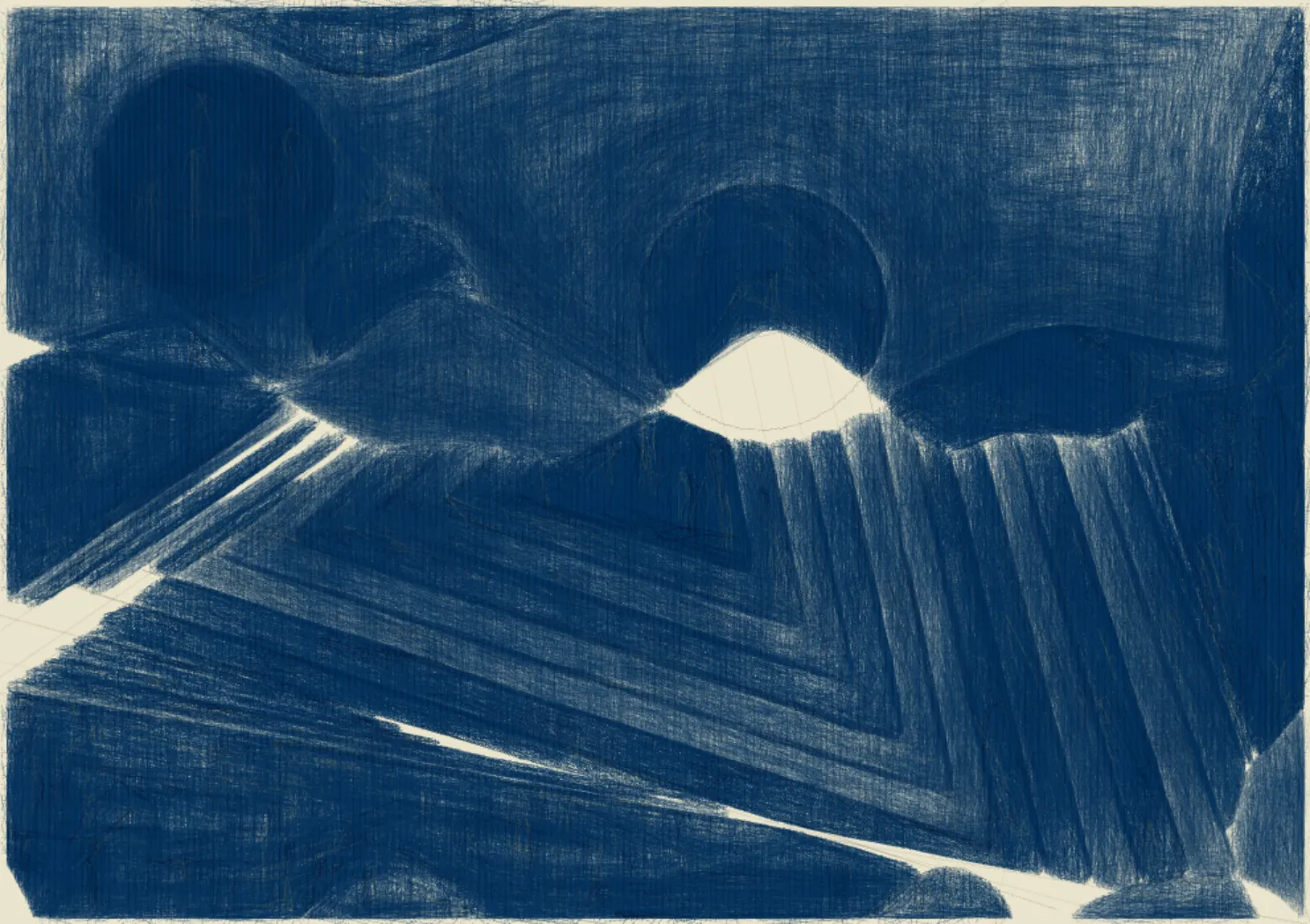

It’s been a process of reflection. When I began Sketchbook B, I didn’t touch the computer for maybe three months. Every morning in the studio, I would start with basic exercises—vertical lines, selecting colors, putting them on paper, doing it hundreds of times—to study my patterns and the way I make marks. Then I tried translating those into code, into functions and math, while still maintaining an organic feel. It was a journey from structure to no structure, while keeping the core of my mark-making.

At each stage, I felt it was the right time to start the Sketchbook B series, which tries to compile all of this into one final expression. The Sketchbook B series is a reflection of how I draw, paint, and engage with the digital medium. It's about the iterative process, and the goal was not to lose my identity in the transition from one medium to another. You often lose something in that shift—and I find that very frustrating.

As a multi-medium artist, I’ve worked hard not to lose what defines me in those transitions. It’s difficult, but over time—and with practice—the bridge between painting and coding becomes stronger. That’s the reflection I’ve been exploring in Sketchbook B.

LF: Thank you so much for that. And now to introduce our panel!

I’ve brought in Peter Bauman and Julia Greenway because they bring very different perspectives. Peter, also known as Mark Anthony, is an arts writer and leads the editorial platform Le Random, with an incredible knowledge of digital generative art. Julia is the curator of the Zabludowicz Collection—a private collection built on the ethos of a public one—and she’s very passionate about digital art. I wanted both of their voices here. Julia works across a wide contemporary landscape, while Peter has deep historical insight.

Peter, I’d love to start with you. William has been talking about the machine as a collaborator—something artists have historically done. Harold Cohen, for example, comes to mind, especially because his painting style mirrored his machine’s logic. I don’t think William lets the machine dictate his creative process, and vice versa. Do you think William is following in the Cohen lineage? And do you see this blending of code and physical practice as something unusual in generative art?

PB: Yes, thank you for inviting me—I'm really excited to speak with William and dive into this incredible series. What struck me about what William just said is how much it reminded me of Cohen. Cohen spoke of his algorithms as extensions of himself. A year and a half ago, we discussed Sketchbook A, and I asked you, William, whether you saw that project as an extension of yourself. You answered that beautifully back then.

Now that you’ve spent an additional 18 months working, I imagine your relationship to the code has only deepened. Cohen also described his algorithms as a form of self-portraiture. Would you say your algorithms are a kind of self-portrait too?

WM: That’s an interesting question. I think when it comes to self-portraiture, I’ve done some painting—but I’ve spent much more time writing code. The concepts I engage with through code have become part of who I am, even as a painter. For me, it’s about exploring composition—what that means from a painter’s perspective versus an algorithm’s perspective.

So if we talk about self-portraiture, it’s more about merging the practices—bringing my human sensibilities into the algorithm. I try to draw the algorithm toward what I know, while also immersing myself in what the algorithm “knows.”

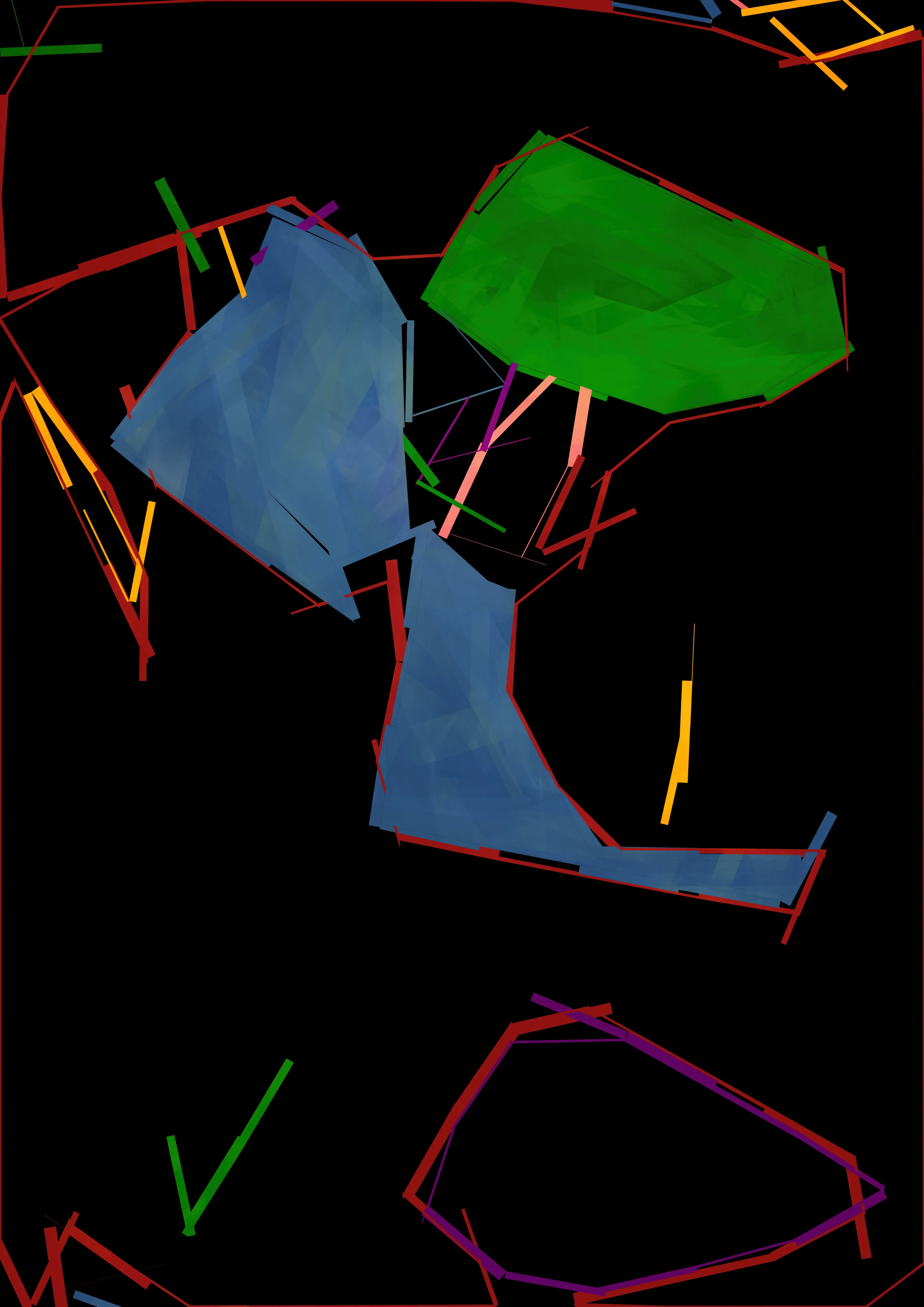

The work is made using basic primitives—circles, triangles, squares. That’s the digital landscape, and that’s the language I use. I’m not trying to mimic painting with code or vice versa. I’m extending myself through the code, using it as a tool that reflects my human experience—emotion, intuition, all of it—filtered through the machine. But I also accept that the machine has its own properties, and I embrace them.

When I code, it’s as though I’m painting. And when I paint, it’s like I’m coding. There’s no barrier between the two anymore.

LF: Julia, I’d love your thoughts on this—on artists using digital mediums as both tool and collaborator. Is this changing the landscape of contemporary art? More and more artists are working with AI. How much do we need to understand that technology as viewers?

JG: It’s definitely happening—and it’s been happening for a long time. Digital artists aren’t new. What’s changing are the tools, the mediums, and how they're being executed.

William’s work, for example, is quite traditional in its visual outcome. There’s a warm, nostalgic, even classical feeling to it. But at its core, what we’re talking about is technology as a tool. That’s always been the case—from early digital artists like Cohen to what’s happening now. Yes, AI has entered the conversation, just as VR and AR did before it. Each new tool brings new forms of disruption and creation.

As an example, Jake Elwes, a London-based artist, works with AI and machine learning. He has a project called Queering the Dataset, where he injects queer, drag, and non-binary identities into facial recognition datasets. The result is a series of generated portraits and figures that reframe those technologies.

Another artist is Christopher Kulendran Thomas, who uses image generation to create JPEG-based works. So yes, artists are using these technologies in meaningful, conceptual ways.

LF: But as a curator, how much do you think the audience needs to know about the tech behind the work? For example, in William’s case, the code is clearly integral. But for viewers walking into the gallery, is it essential that they understand it’s algorithmic?

JG: That’s a great question. I think it depends on the artist, the curator, and what you want the audience to take away from the experience. If the process is central to the concept, then yes—it should be made visible. William has done that by including the plotter and the live generation setup in the space. That shows the code is key to the final result. But how much is hidden or revealed is up to the artist. It’s about communicating the intended concept, and that determines how much of the technology you foreground.

LF: Peter, I want to bring it back to you—how alive is generative art today? Two years ago it was all about the code. Has that conversation shifted?

PB: It’s definitely shifted. We’ve moved from discussions about output space to now talking about latent space—especially with the rise of AI. That’s one thing I find particularly fascinating about William’s practice. We spoke privately once about how your work is changing your brain—literally changing the way you think. That really stuck with me.

In traditional painting, we talk about pictorial space. With generative art, we deal with output space. AI adds another dimension: latent space. How do you see these spatial concepts—pictorial and output—interacting in your work? Why move beyond traditional pictorial space?

WM: Your article really pushed me—it helped me ask myself: how do I explain my practice? Even among other artists, it can be hard to communicate this shift in perception. My brain truly works differently now. I often compare it to the first time someone uses Photoshop—suddenly you realize how images can be manipulated, and that changes how you see the world. You start noticing what's real and what's altered.

It’s similar with algorithmic thinking. My brain now tries to systematize things—automatically. I make connections and build structures unconsciously. That’s why I spent so much time in the studio. I knew that the more I practiced, the more naturally my brain would build systems to make sense of my mark-making.

If I can systematize that—my identity, my style—then I’m digging deeper into myself. It becomes a new way of seeing, a new way of thinking—through systems, code, and algorithms.

LF: It really is. And I’ll be honest—we’ve struggled to curate this show. William is such a digitally native artist, and his work really lives in the browser. One of the things we’ve talked about is how his code renders differently on different browsers. That variability is something he respects—it’s part of the work. But it’s hard to translate that into a physical exhibition.

Which is why we’ve included the live coding station—so people can generate in real time and really see the variability. The more you generate, the more you understand. But still, I wonder—are we being pretentious by bringing this into a gallery? Should this work stay online?

PB: I love that you’ve brought it into the physical world. You get to see the dimensionality—the plotted lines, the little pool of paint. It reminds us that this work isn’t just flat pixels on a screen. It has depth, texture, presence. Digital work is often flattened. But seeing it physically helps you connect in new ways. That reminds me of a bigger question—Tina Rivers Ryan recently told me one thing missing from this space is artists who speak the language of contemporary art. So I’m curious—Julia, William—how important is that to you when meeting artists? Do you discount those who can’t speak that language?

JG: Do we need it? Yes. Can we also define it? I think there are many ways to move through contemporary art spaces. There are artists who work with markets and commercial galleries, and others who work in institutions or social spaces. There are just so many ways to navigate a career. What’s inspiring is seeing artists who holistically create their work—doing what they need to do to make that happen. It’s about finding the right placements, outcomes, audiences, and support. Go ahead.

LF: I just had a realization. What you’re really saying is—can you market yourself as a contemporary artist? That’s an interesting question.

JG: Yeah—find your people, find your public. I don’t think it always has to be about the market. You can work with funding bodies or find other ways to sustain your practice. You have to play the game a little, but I hate to say that—it’s not entirely true.

LF: And with William, even though he’s well known in the Web3 and digital spaces, I consider him the ultimate contemporary artist. He’s exploring what it means to sketch in 2025 using code, plotting, and various mediums. It’s a way of thinking—of understanding form, color, and self-expression. That’s ultra-contemporary. What makes him serious is the consistency. He’s been deeply exploring a particular path for over two years. Peter, correct me if I’m wrong, but that’s rare.

PB: I definitely want to hear more from William. But what you’re saying reminds me of something the curator Helen Molesworth once said (not the one at the V&A—the one from LA who was at MOCA.) She talks about the “speed of art”—how it should be slow to balance the chaos of modern, networked life. I always found that idea interesting, though I don’t fully agree. I think art should unfold slowly, sure—but it should also speak to what’s happening now. So I think we need both. William, I feel like your practice perfectly embodies that balance—you work with algorithms and blockchains, but also allow things to unfold slowly. Do you agree with Helen? How does working with code and blockchain influence what you’re trying to say in your work?

WM: Code is really interesting. I think art should question the world—challenge it. If the world is fast, make it slow. If it’s slow, make it fast. That’s what art can do—what else can? For me, it’s about intention and choices. Code gives you this computational power to explore things at an incredible pace—faster than any artist 50 years ago ever could. That’s what makes it contemporary—code is central to everything today. Everything is algorithmic. So how do you use that as a medium to express your own voice? That’s what I focus on. It’s not about speed—it’s about intention. Speed is a component, sure, but in my practice, I explore quickly and choose slowly. I immerse myself in fast, generative universes—but reflect on them deeply. That’s the slow part.

PB: With work like Sketchbook A and Sketchbook B, which span years, I wonder—do you have a hundred other ideas you’re ignoring to focus on this one? Or is this all you think about?

WM: It’s a mess, honestly. I have multiple algorithms running at once, but I try to focus on one subject at a time—sometimes for months or years. Different branches emerge, but I try to stay centered. You can feed yourself infinitely as a generative artist—one idea leads to another, and another. Sometimes you go forward, back, sideways—it’s endless. Traditionally, inspiration came from the outside world, like painting nature. Now, I can be inspired by my own progression, by the systems I create. So yeah, I have new ideas daily—I write everything down.

LF: How do you choose?

WM: I ask, “What do I want to explore?” and “Which idea matches this concept?”

LF: I want to bring in the blockchain aspect. Both collections are on-chain. Your work is, as Julia said, quite traditional—many of my friends compared your compositions to great abstract painters. Why does being on the blockchain matter to you? It’s clearly not about the money—it seems like a conscious choice.

WM: Yeah, thanks to Matt DesLauriers—he told me one day to check it out, and since then I’ve been in it. For me, the blockchain is about marking your presence in the digital medium. Before, digital work could just vanish—lost on an external drive. Blockchain gives you permanence. It’s like a massive library where, even if everything else falls apart, your work still exists. It’s about being present in the world and true to your moment. Also, there’s a community aspect—suddenly, anyone anywhere can connect with your work.

LF: Sketchbook A was generated 1.5 million times. I’d love to see how that number grows. That kind of engagement—momentum—makes total sense. Julia, why do you think the traditional art world still has trouble accepting this?

JG: I can’t fully answer that. But yes, there’s a weird divide. During the NFT boom, there was a push for collectors and institutions to get involved. But it really takes active engagement from collectors.

LF: And your institution has acquired NFTs, right?

JG: Yes, we’ve added quite a few NFTs and even commissioned some. That’s rare—it’s refreshing to see a private collection take the lead. But we need more from institutional spaces.

LF: Do you think institutional validation bridges that gap?

JG: I think it helps. And we’re seeing that shift. The more we host blockchain work and discuss things like authorship, the more the gap closes.

LF: Have you exhibited NFTs? Institutions only show a small percentage of their collections—maybe 1–3%. What would an ideal exhibition look like?

JG: Great question. One of my early shows at the collection was Among the Machines—it explored AI and advanced tech. We considered including NFTs, but didn’t want to just put them on a screen in the lobby—it felt cheap. That approach doesn’t honor the work or process. It’s still a tough problem—how to display NFTs authentically. We need to keep trying, though. These works are crucial.

WM: That question won’t be solved soon. Technology moves too fast for humans—and even hardware can’t keep up with software. The perfect display for digital art doesn’t exist yet.

LF: Institutions need to keep learning. But it’s also about people and energy—the momentum that happens around releases. That energy is almost like a performance—ephemeral, unrepeatable. So, how do we merge these two worlds?

PB: For me, it’s not so much about blockchain or NFTs—it’s about digital work and who’s making interesting digital work. Blockchain is often perfunctory unless it’s part of the concept for example with art that explores the blockchain’s unique characteristics of “protocol art,” or “blockchain formalism,” which is a term coined by Mitchell F Chan. But often, the conversation around NFTs in the contemporary art world focuses on markets and economics, and there’s less time and attention given to the vision or concept. That’s why some institutions don’t engage. It’s about having a vision and knowing how to articulate it.

PB: William, your practice could easily produce beautiful one-of-one pieces. But you think algorithmically. You explore systems and output spaces. Was that what drew you to the blockchain—being able to explore more than a single outcome?

WM: You don’t need NFTs to do that. But it becomes a performance. Like Leyla said, it’s social. People participate—they trigger the algorithm and become part of something bigger. That wasn’t new, though—we were doing long-form generative work before blockchain. The blockchain just made it more public, more performative.

PB: So it was the community and coordination aspects that drew you in?

WM: Yes. The blockchain changed how I thought about my practice. Before, I made systems, but not full universes. The blockchain made me think in those terms—systems that can unfold on their own, where I don’t control the final output. That constraint changed my approach.

JG: How were you showing work before the blockchain? Was it selling?

WM: Honestly, the Web3 space gave me a stage I didn’t have before. I was mostly working as a creative coder. The social aspect of this world put a spotlight on me. That’s why I’m here today—because people saw me and supported me.

JG: That’s amazing—that it opened up for you like that.

LF: So what’s next after Sketchbook—besides getting some sleep?

WM: Sketchbook is my daily life. It’s not something I stop and start—it’s continuous. Tomorrow, I’ll go back to the studio and keep sketching. Maybe someday there’ll be a “C” or a “Z,” who knows?

LF: All the way to “Z”!

WM: It’s not a “series” I plan—this is just how I live. I sketch with my son, we explore ideas, and I build systems from those little moments. Market or not, this is just me.

LF: That’s exciting. Thank you, William—and thank you, Peter and Julia.

Audience Member: I have two questions, if that’s okay. I was really interested in those first few months you mentioned—when there was no code. You said your brain changed. During that period, how much was feel versus think?

WM: We have different parts of our brain for different things. The part I use to paint isn’t the same as the part I use to code. At first, I just let myself express—no code at all. Pure feeling. Then, slowly, the coding brain knocks on the door and says, “What do we do with all this?” That’s when the thinking begins.

Audience Member: Can you put a percentage on it—how much was just flow versus thinking about code?

WM: At first, it was probably 90% flow. Using your body, moving around—it’s almost disconnected. Then, over time, that shifts. The coding brain gradually joins in.

Audience Member: Do you dream in code or in outputs?

WM: Both, I would say. The turning point for me is every time I say, “This is about to be finished,” I start dreaming about the system. You have the code, and you split the system. The last time was, I think, three weeks ago, when I was under a "Sudanese" of code—my little code about writing—and I was dreaming of crayons falling from the sky. It was a messed-up brain. And then you wake up like, “Okay, I’m really into it.” This is usually where I know: I’m near the end. It needs to end now—somewhere near, somewhere soon. That’s fine. Thank you.

LF: A great one to share. Any other questions? Oh—two questions.

Audience Member: Thank you, William. This is an incredible exhibition. I just wanted to add a thought—many pioneering artists talk about randomness as being an incredibly important element of our practice. I just wondered how much you see randomness within the algorithms as a crucial element of your work.

WM: Yeah, I would say it’s at the core. Like, everyone I see, we all say it’s at the core of the practice—because you make a choice to not choose. You make a choice to be surprised by your code. And the more you chain random components, the more complex your universe becomes. So yes, it’s at the center. But at some point, we don’t think about it anymore—it just happens naturally. You go, “On this road, I’m gonna pin this point and make it from there because I want to be surprised.” And it just becomes instinctive—it becomes natural. It’s a way of drawing: you draw, but you have another driving force that you don’t control. This tension becomes natural, and you can loosen it or make it stronger. It just becomes something you don’t even think about anymore. I don’t.

Audience Member: Do you think it becomes part of human intuition—like the creative intuition you have?

WM: Yeah. And I think it changes my brain, even when I’m outside. I see scenarios—like this car could go left or right, but if it goes left, this could happen. But what if it goes right? Just building scenarios. It’s a bit mad, yes, but the way the brain operates... at some point it just becomes natural to imagine possibilities. Yeah, that’s the core. It becomes not even a subject anymore—it’s just normal. It’s another language.

Audience Member: Can I ask one final question? I’m intrigued by the fact that you now have a child—and they have incredible, free intuition that’s uninhibited. Have you been inspired by that aspect? Seeing a child experience creativity for the first time?

WM: It’s definitely been interesting to see him evolve. From the very beginning, he gets a crayon or a brush and just makes stuff. And the more he grows, the more his environment affects him—unconsciously. He’s not even aware of it. But now, he can’t make the things he was making two years ago. I’m really interested in that as well—why can’t he? What blocks him? How can I trigger those things he could do before? And it sends me back, as well, to my own condition as an adult. How can I break the things I believe in? What are my stoppers? How can I break everything to go back to that instinctive drawing—not always the usual way of doing things? It’s been tiring to see him work, at least, and even more so in how it sends me back to questions I had before.

LF: I think Rago had one question—and then we’ll wrap up.

Ralgo: That was actually a lovely question—the previous one—because I know you’ve been inspired by Paul Klee, and that sort of childhood link is very interesting in general. My question is just trying to understand: how do you feel about AI? And how do you feel like you might integrate it into your work in the future—or not? It’s a great question because you stay true to a pure generative form, whereas I know a lot of people are now looking at how it all mixes together—AI and generative. So it’d be really interesting to hear your thoughts on whether or how you might integrate it.

WM: Yeah, it’s a question I get a lot. For me—I’m fine for now. I already have a lot on my plate that I still need to explore. Having an external universe to explore... I have so much already to think about, so I’m not into it yet. I think I don’t need it. I just like to think on my own. I like to be inspired naturally—and I’m not willing to have... I mean, AI is another medium. And as I said, as soon as you use another medium, the question becomes: how do you keep yourself in it? AI is a big danger in that sense—you can lose yourself in it. How do you inject yourself into this world—this dataset, this sea of data? So I am very careful in my use of AI. I’ve tried it, obviously—I’m a technologist as well, so I try stuff for fun. But I didn’t see the interest so far. I’m just like, “Yeah, maybe later.” But as a way of outputting something into the world? Not yet.

However, as a tool—generating colors, training it on my own color palettes—why not? If it’s part of the process, sure. But if it contributes directly to the final output—not yet.

LF: Thank you, William. Thank you, Julia and Peter. So great to have your insight—and always so nice to hang out. Thank you to everyone who made it this evening. It’s been so lovely. Thank you so much. Hang around for a glass and enjoy the rest of the exhibition. Thank you!

William Mapan

William Mapan is an artist based in Paris who has garnered significant international attention for his generative practice. With a background in software development and visual art, he combines computer science with his passion for pigment, light and texture. He is known for his ability to replicate the materiality of physical materials in his work, transforming the digital canvas into a textured...

Leyla Fakhr

Leyla Fakhr is Artistic Director at Verse. After working at the Tate for 8 years, she worked as an independent curator and producer across various projects internationally. During her time at Tate she was part of the acquisition team and worked on a number of collection displays including John Akomfrah, ‘The Unfinished Conversation’ and ‘Migrations, Journeys into British Art’.

She is the editor...

Julia Greenway

Originally from Detroit Michigan, Julia Greenway’s curatorial practice focuses on how digital media influences the aesthetic presentation of gender, economics, and environment.

Currently a curator at the Zabludowicz Collection, London, she has presented the solo exhibition by artist LuYang and the thematic group exhibition Among the Machines. Previous roles include the 2017-201...