Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

At the Intersection of Art, Materiality, and Process with Kelly Milligan

Verse caught up with Kelly Milligan to discuss his new series Microplastics, as well as his thoughts on generative art and art history.

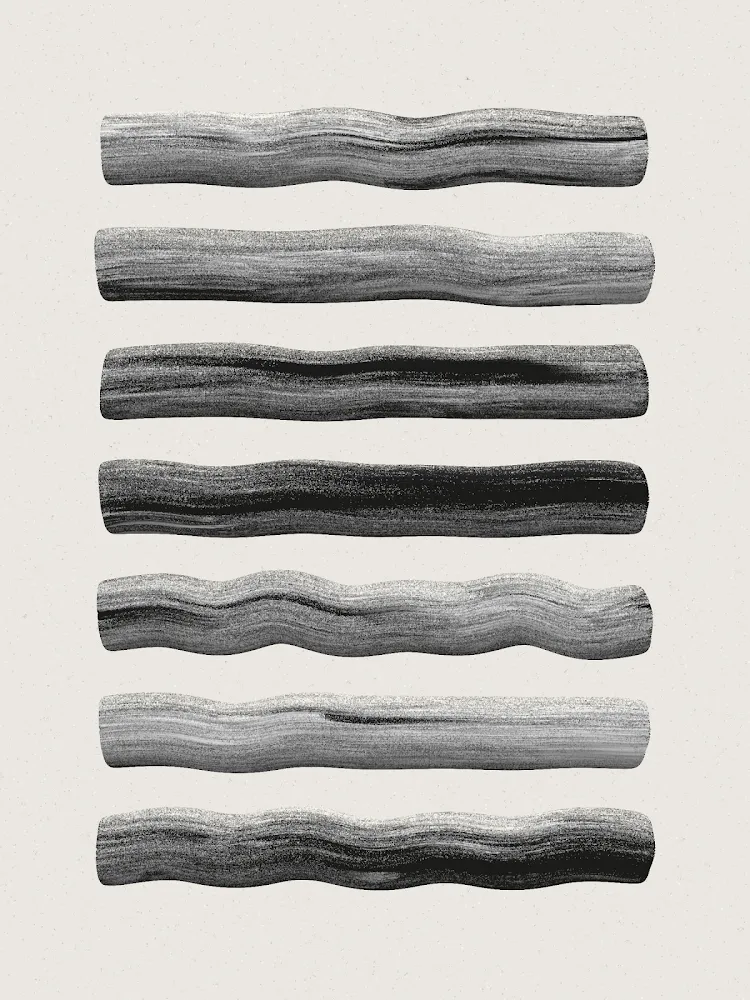

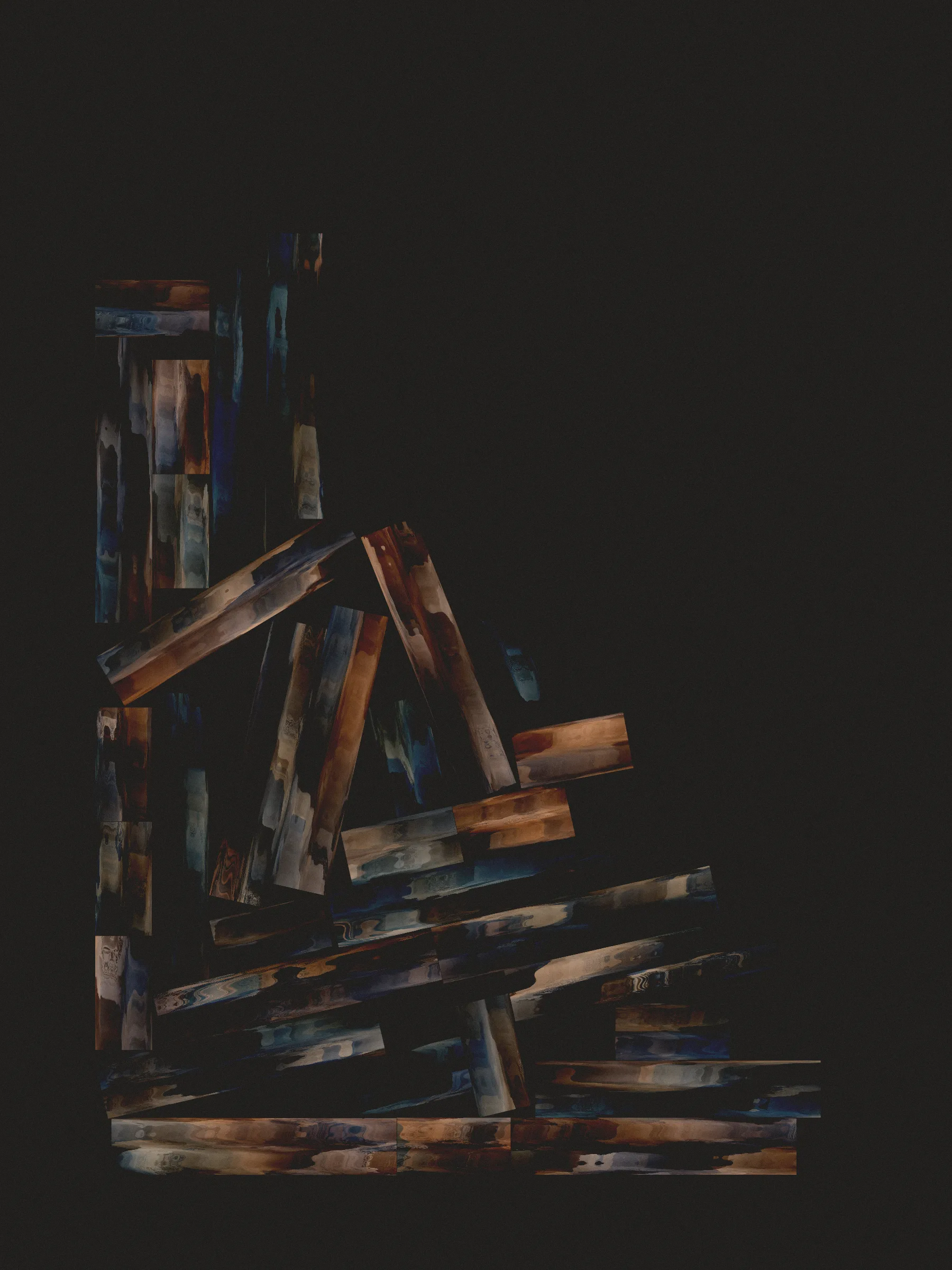

Microplastics, Kelly’s new series is a conceptual, detail-rich critical commentary on the harmful effects of microplastics on aquatic ecosystems. He makes the works using a 2D rigid body physics system, which as he explains is a ‘rudimentary way of trying to mimic the physics of the real world in digital graphics’. Within this digital sandbox, he injects between fifty-to-a-hundred thousand objects to interact with each other – each one jostling until they find an equilibrium. All the bodies are entirely tensile, meaning they can’t change shape or morph. Larger objects have more mass, thereby dominating amidst the chaos.

Within these tightly packed environments, Kelly explains he’s most interested in the texture and natural behaviours that emerge as the physics simulation follows its course, generating unique outputs each time. Rich, organic textures are a constant across Kelly’s series, and with Microplastics he emphasises the ‘resolution changes’ that occur when you zoom in and out. Up close, each shape is flatly outlined in sharp detail, but stepping back you begin to get a sense of what Kelly describes as ‘water-like effects’, as the works emerge into an unexpected whole.

He imagines the series as evoking a sluggish urban river, clogged with junk and detritus. The work cleverly mimics both the appearance of the river to the naked eye, as well as its microscopic make-up – where minute particles of plastic eek their way into every corner the ecosystem, causing havoc as they break down into infinitesimally smaller pieces. Discussing the possibilities generative art affords him as an artist, Kelly makes clear he sees generative art as ‘more of a process than a medium’. ‘For me it’s more like I’m using the computer as a tool to push the boundaries of what I can create.’ The sheer detail of the series makes this abundantly clear: each work within the Microplastics series can take fifteen minutes to render, due to the number of calculations involved to determine the eventual resting point of each individual object.

Physics engines generally limit such precision in the name of performance, and so it was only by disconnecting render resolution from engine resolution that these collisions and eventual equilibriums became possible. (This lengthy rendering time means that the works Kelly has created for Odysseys are therefore generated before the exhibition drops, so collectors don’t have to wait). Kelly understands the creative synthesis between computer and artist as an ‘augmented’ dynamic, ‘empowering you to do things that you otherwise couldn’t’. Notably, he views the work of art as the ‘the system that spits out outputs, and that the individual works are in a sense derivative of that system’, although he chuckles that ‘the market probably doesn’t agree with that’.

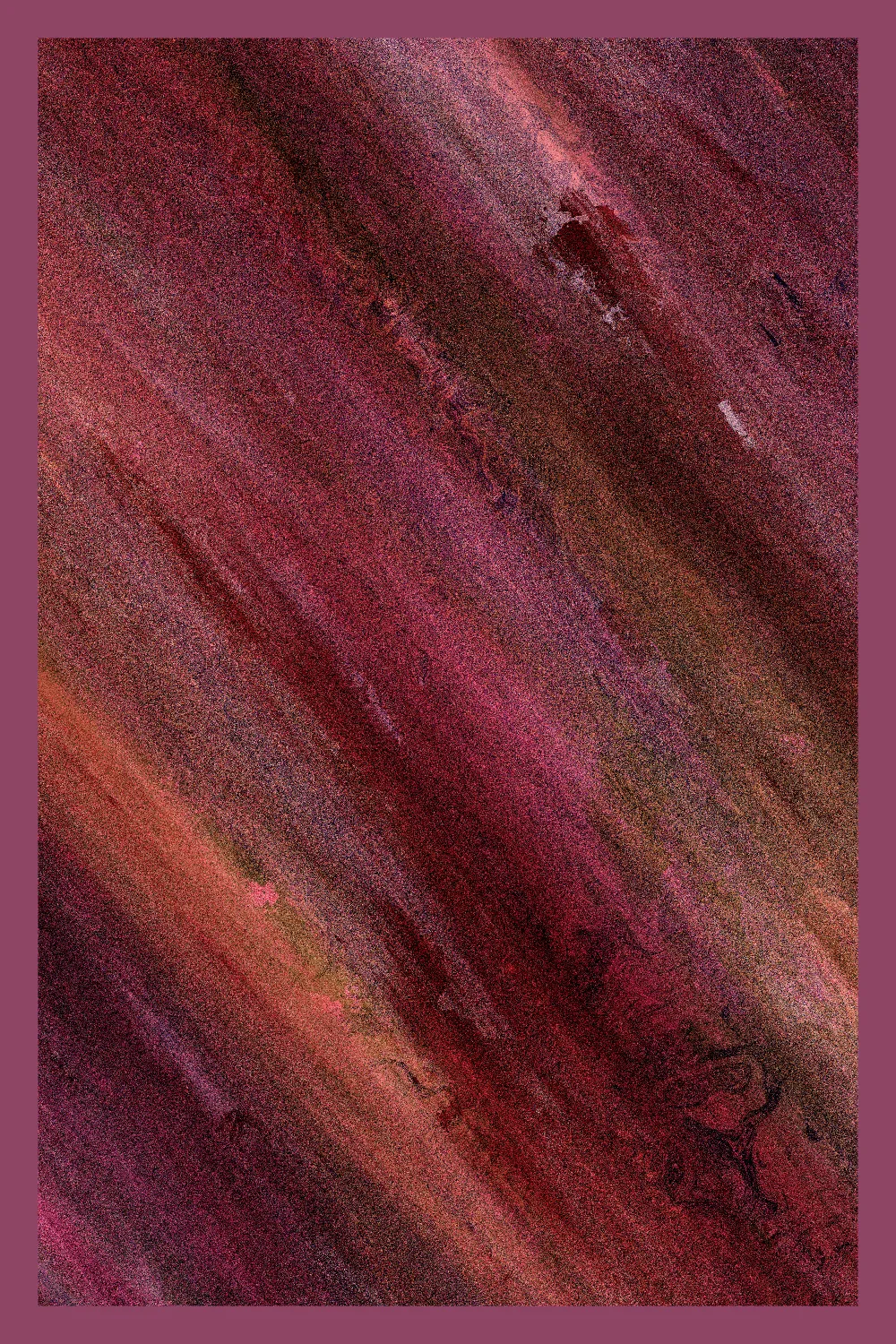

Kelly’s previous series similarly strive to bridge the gap between the physical and the digital. Act of Emotion, a curated release on Artblocks in 2022 ‘investigates digitally facilitated abstract expressionism: the act of painting itself as a means of expression, extended into mechanical reach’ in Kelly’s words. Although so much of our common understanding of Jackson Pollock – someone Kelly took inspiration from in this series – revolves around the embodied presence of the artist and his heroic gesture, Kelly unearths a wholly different understanding. ‘I think with action painting, and Ab Ex, a lot of those artists describe a process that’s very automatic, almost procedural – with Pollock he’s got that process, and he’s doing it over and over again. Tweaking little parameters’. Kelly describes Pollock almost as if he’s following his own primitive algorithm: an artist-machine hybrid that spits out artistic intuition.

This understanding of artistic intuition as a type of instinctive quality control connects to Kelly’s own understanding of the role of a generative artist. He explains that an ‘important part of the generative process is having an eye so you know what people will emotionally connect with. Our job is to therefore identify when something is resonating - and it looks like we want it to – and then guiding the system down further and further towards that path. Because if you’re throwing random things on screen then it’s just going to feel cold and arbitrary. But as soon as you start focusing things and honing in, that’s when you start to feel that real natural warmth that any artist is any medium is trying to create’. Asked about his native New Zealand, Kelly confirms it’s ‘his favourite place’ as well as an important part of his work. He talks about how generations of Kiwi artists (including Colin Machon, who used to live in the neighbourhood where Kelly now resides) have subsumed the island’s calming greens into their palettes. With regards to the connection between the natural beauty of his locale and his own generative practice, he explains his work ‘leans on trying to find that intricacy of detail that you find in nature, so that even though the work is digital – it feels organic and familiar’. In Kelly’s work nature and technology reconcile; code becomes an original enquiry into ecosystems, an abstract rendering of their complexity.

Kelly is an artist that imbues the digital with feeling and warmth – daring to show us that it is not only the human touch in art that can move us. His work thereby reflects widely on the future of automation, machine consciousness and creativity.

Kelly Milligan

With roots in creative development in the browser, I translate practical code patterns into algorithmic and generative art: for-print, in-motion, and fully interactive. I aim for organic texture and bold colour. I love results with unexpected form and tech-driven complexity; they push the work beyond what's possible with traditional methods. I brew a mean beer and cook a fine meal. I love...