Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Twitter Space: Creative Control - Authorship & AI with Roope Rainisto

Holly: Welcome everybody. I want to say thank you to you for joining and thank you so much to Jon and Roope for being here with us today. Super excited for this conversation - they're both such passionate artists and know a lot about each other's work. Jon's done a lot of research and Roope influenced his style to an extent and it'll be a great conversation.

Jon Wubbushi: My pleasure to be here. I'm so excited. Roope has been a big inspiration for me since day one. My AI hero so to speak. So let's jump into this. You've been a hero of mine. You bought one of my pieces. I didn't know who you were and that was that at the moment you basically launched Life In West America. And then a couple of days later, I was just driving down the street. I was listening to the Kevin Rose podcast and they're talking about you. And I had to pull over my car. I was like “Oh my gosh, that's the guy I've been talking to”. I've always looked at your work in huge admiration. It always moved me, moves me deeply.

And it's one of those things, with certain artists you can just look at and they move you. One of my other favourite artists is Cy Twombly, you look at him and I don't know why, it's scribbles, it's whatever, but it just has that, that effect that really, really moves you.

So the first question I had was what are some of your favourite artists? Maybe the first artist that comes to your mind when I ask you that. And why do you like them?

Roope Rainisto: I think I will answer broadly, let's say Franz Kafka or David Lynch. I think these are probably my favourite artists. But I don't think I'm inspired by artists. I'm inspired by lots of music, movies, books and visual artists and so on.

Jon Wubbushi: I've seen you play the guitar; you're also writing a film play – you’re doing all of it.

Roope Rainisto: I'm not saying I play well, but I play. And I think for a lot of the artists it's not so much about the technical skills. I think quite often one might even say that sometimes the artists that have the best technical skills are slightly less interesting because the humanity in art overall comes from the fact that it's human. And I think humanity ought to have some flaws and imperfections.

Holly: I think that's lovely in the sense of your work being so much about emotion and emotion being so much about connecting with other people and having a shared experience. Because you can connect with someone over the technical side of your work, you're sharing tips and getting excited about a new technique, etc.

But it's a very different experience that maybe you could say is somewhat removed from the art. The focus of your work is entirely different. And I love the fact that that translates to what you enjoy outside of what you create as well.

Roope Rainisto: Yeah, of course, good art, hopefully, comes from the personal experiences. I think many artists have their own quirks, their own reasons why they create. But I think it's been quite important to try to stay true to them and then to try to create the art that that you enjoy yourself or that you wouldn't enjoy yourself rather than trying to create art that you think that somebody else might enjoy.

Holly: Is that so for example when you're curating your own works and you're going through the outputs that you have you might be swayed if you look at a work and you're reminded of an experience that you've had, whether that's from your childhood or a birthday of one of your own children or a fun day last weekend, whatever it may be, that that influences your curation as well because it connects with something inside of you.

Roope Rainisto: Yes certainly. I think a lot of my art is about the curation side. I've been asked to do AI art collections that are long form, meaning that I create the model, but I don't control the end result and I've never been able to do that in a way that I would be happy because even when I do, even when I create art myself the 99.9% of the things I create are bad or are not interesting to me. And I think that long form for me is the same if I would go outside and take a 1,000 photos and I would share the 1,000 photos. And I think that's weird because the good is rare.

Jon Wubbushi: I found that when I'm making a work, I will start stumbling into things and that resonate with me. What is your process like? First of, when you start working on a collection, Vacation or whatever it is, how do you stumble into it?

When does it start getting meaning? How does that meaning develop? And then also, have you learned more about yourself? Throughout this process that maybe and how that be different, normal or traditional.

Roope Rainisto: Yeah, that's an extremely good question. And I think that goes to the core of AI art overall. I think people talk a lot about who is in control in traditional art and in traditional tools. If I would draw something on paper, people might think that I would have that quite strongly in my mind before I start to draw. And this is not 100 % true, sometimes you can get inspired in the process, but I think AI is a bit more than street photography in that way. When I do street photography, I do have a plan or, or some idea of want to do. But it's then only at the moment when I come to the place I will actually see if there's something interesting going on. So, something completed unexpectedly that I find on the streets that I had no plans of beforehand.

So I think this also works AI art. I have some idea that I want to do these types of pictures, for instance in Vacation. But it's only when I start to create, and I see the results, I see the choices. And after I do that 5 times or 10 times, each time I go deeper and deeper. I might then change my plans, or find something that was much more interesting than the thing that I had in my mind the first place. And I don't think that's a bad thing.

That's a good thing. It's a feature, it makes AI art interesting, and you start to go deeper and deeper. And I think that's the way almost all AI artists that start with AI work. Their first mistake or the first thing that they do is that they share their first outputs. But I think that the more time you spend with this, the more you start to feel the urge to go deeper and start to explore or to need to create something that feels more personal to you.

And that's why I find this process so much more fascinating than writing poems or books or playing in bands, writing songs and so on. I've done a lot of arts, but I just find this process to be so fascinating.

Jon Wubbushi: I experienced that when I first got into it. I was worried that my authentic self, my soul wasn't being expressed as well as if I was painting or something like that, but the more I got into it, I realised that you have so much more dynamism in terms of what you can express. If you’re a painter you can spend three, four, five years developing a style, developing a specific look, a signature style. Whereas with this, you can define exactly the look and feel fluidly. Have you found that, compared to your other artistic medians, you can express yourself better, worse, the same, or indifferently?

Roope Rainisto: Well, I'm not sure about the word better, because each form has its differences.

I don't think AI tools, at least today are a perfect solution to all. I think as with all mediums, they work great for some expression and not all in others, same as with painting or photos and so on. They are not the best for all needs, but they are great for some.

Jon Wubbushi: You mentioned to me in a comment a couple days ago that good artists or good art can have the viewer feel the feeling the artist wants. In your process of creating Vacation at what point do you realise the feeling you're trying to get across? How many images into it? You said you started this process in November. When did you say, okay, this is the feeling of the collection? And I'm also curious what the feeling I'm supposed to get with it is.

Roope Rainisto: Art has many definitions, but I resonate with the romantic notion that art is a means for the artist to evoke emotion in others. Unlike a simple email, which communicates information, art strives to make you feel something. This is crucial because each of us is fundamentally alone in our emotional experiences. We can never truly know what someone else feels, despite their attempts to express it through words or expressions.

Creating art is a personal endeavour. I create pieces that move me, though I can't be sure they will evoke the same feelings in others. However, if my work doesn't stir any emotion in me, it's unreasonable to expect it to affect someone else.

Our individual experiences shape our reception of art. What I express through my work might not resonate the same way with everyone, and that's perfectly acceptable. My relationship with art is complex, especially when exploring themes like 'vacation,' which I find fascinating. Vacations often represent an escape from reality, a break from the routine to experience something magical or fantastic moments that stand out in our lives.

Yet, my own vacation experiences often feel mundane, reinforcing the idea that the world is fundamentally the same everywhere. This duality—the expectation of something extraordinary versus the often-underwhelming reality—mirrors the broader contrasts in life and is a theme I explore through my art.

Good art, to me, isn't one-dimensional. It's easy to create a sad piece, but truly engaging art contains layers of conflict or tension. It allows for multiple interpretations, making it far more intriguing than art that is merely happy or sad. This complexity is what I aim to achieve in my work, ensuring it remains thought-provoking and open to various interpretations.

Jon Wubbushi: It's funny, when I first started talking to you, I looked up to you a lot, and I worked really, really, really hard, and I got this great collection that I wanted to show to you, and your response was “It doesn't really make me feel anything”.

“I don't know what to feel” is what you said. The goal of art is to make you feel something. So then I was like: “Great, okay. I got this mission now. I got to make my art feel something.” And then I worked really hard to make art that felt something. And then, months later, I understood what you meant about feeling something.

It's about feeling a specific thing. And it was really this crazy learning experience for me, and I really appreciated it. So, when I looked at Vacation the words, I got for my feelings were sad, lonely, and regret, actually. I don't know if that mapped to where you're thinking about but that was the feelings I got with it. And, I know you said you're not looking for a specific feeling but I wonder if that's accurate. And is that the feelings you have when you look at it?

Roope Rainisto: The predominant emotion in my work may be sadness, but I aim to pair this with external beauty. For example, consider vacation postcards. I find these fascinating. The images are always nostalgic and sunny, presenting places in a magical, somewhat unrealistic way. This visual style is intriguing because it attempts to blend reality with fantasy, creating a compelling contrast.

I'm pleased that the sense of sadness resonates with viewers. However, my goal is to also capture the reasons behind why people seek these experiences. People often use vacations to escape—not just from their daily lives, but from their very selves. On vacation, you can let your hair down, assume a different persona, or embark on a romantic adventure. These possibilities are a rich source of inspiration for me and influence the themes I explore in my art.

Jon Wubbushi: I looked through all the pictures and I read your titles for them. I'm curious what your style is for coming up with those titles and if there're any ones that reflect your personal history, the one that I'm specifically thinking about is called Pregnant Wife.

Roope Rainisto: When it comes to naming my art, I follow a simple, intuitive process. Initially, I jot down the first thing that comes to mind without overthinking it. These initial ideas often don't make logical sense, but they spark something meaningful. The next day, I revisit these titles to see if they still resonate.

I believe a good title should hint at the artwork’s meaning without being too explicit. It's like planting a seed in the viewer’s mind, similar to the subtle cues in the film 'Inception,' where hints encourage viewers to derive their own interpretations.

Everyone views the world through their own lens, influenced by personal backgrounds and experiences. If someone interprets my work differently from my intention, that’s not just acceptable; it’s valuable. Interpretations are personal, and the diversity of these views enriches the conversation around art. My background might shape my creations, but your perspective is what completes them.

Jon Wubbushi: When I first explored art, I was surprised at how quickly I created work that was not terrible, despite having no prior experience. This led me to a realization: AI is set to dramatically elevate art across the board. This belief fuelled my passion and convinced me that a major movement was underway.

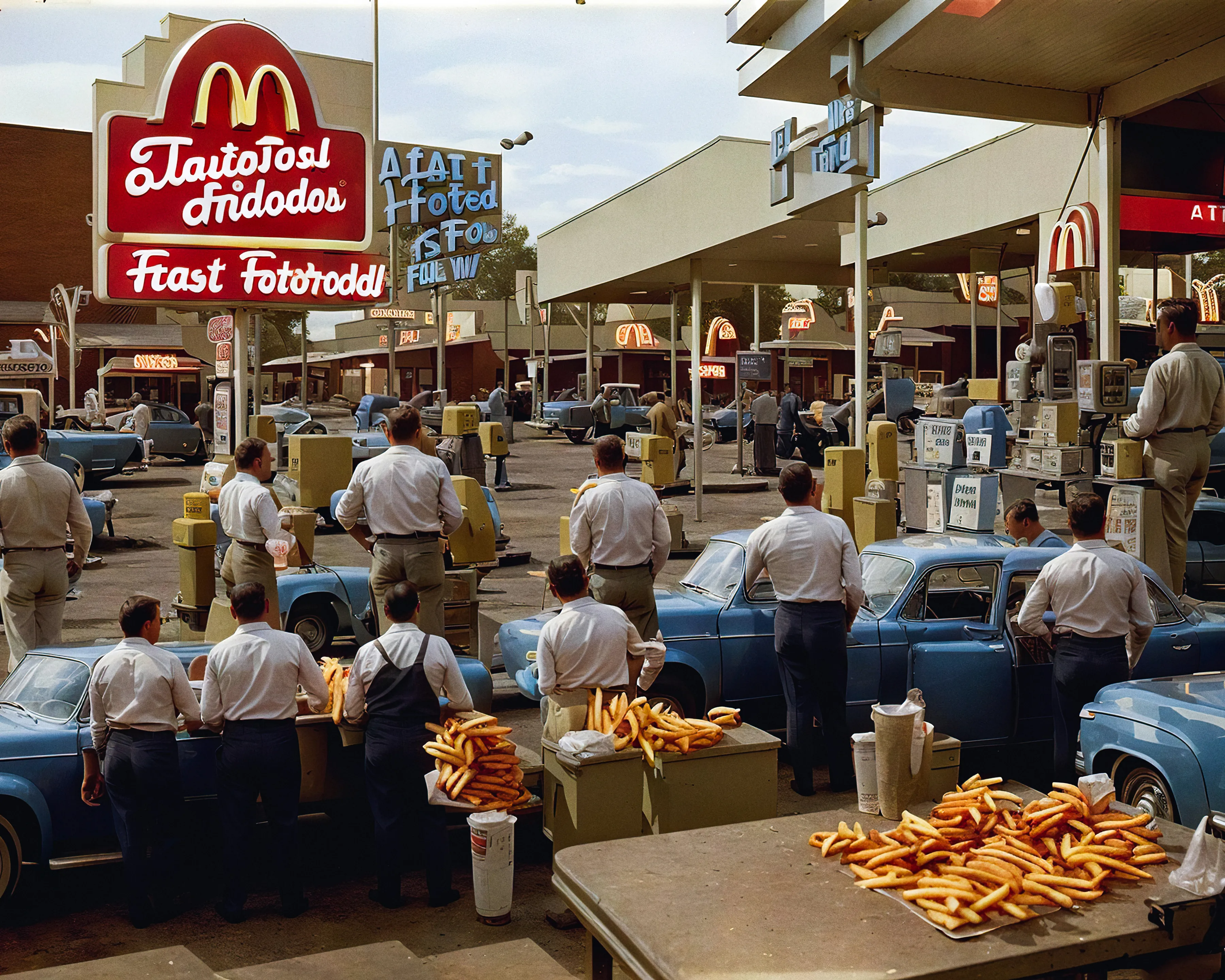

However, this epiphany also sparked a frenetic desire within me to establish a leadership role in this emerging field. My moment of clarity came when I saw Life In West America. It was challenging, and exactly what I wanted to pursue. I aimed to push technological boundaries, making the hardest choices to produce meaningful art.

As I progressed, it became apparent that creating perfect images was becoming effortless. This realization prompted a shift in my focus towards creating Timeless Art—art that isn't solely about technical perfection. What about you? Have you always gravitated towards creating 'Timeless Art' that eschews perfection? Could you share your thoughts on this approach?

Roope Rainisto: That's a great question. I didn't initially set out with a clear goal; I stumbled into this approach. I've been focused on generative art for about two and a half years, inspired by the idea of a 'virtual camera' that allowed me to explore art through photo shoots. Initially, my goal was to create photorealistic images that blurred the lines between AI and actual photography. Over three months in late 2022, I worked intensively on achieving this realism.

However, I found that the images that didn't achieve perfect realism—those that 'failed'—were more interesting to me. The more lifelike the images appeared, the faker they felt. This led to a realization: authentic art to me wasn't about perfect replication but about evoking thought and questioning reality. If an image is too real, it doesn’t challenge the viewer; it’s just a flower, nothing more.

Interestingly, I see all photos as inherently 'fake' to some extent—a social contract we abide by pretending they depict reality. With AI, you have two paths: replicate existing forms or innovate new ones. For me, the latter is far more fascinating. Using AI to create art that could not exist otherwise opens new forms of expression and challenges conventional expectations of what photography should be.

This shift led me to experiment with photographic styles not to mimic photos but to play with viewer expectations and explore new artistic possibilities unique to AI. This approach, once realised, became my niche in the art world.

Jon Wubbushi: One question people often ask, especially after you mentioned starting with a hundred thousand photos for Vacation, is how you maintain focus and avoid boredom through such a massive undertaking. In my experience, working with AI feels like exploring uncharted territory. It’s akin to being a pioneer in a new world without a rulebook, constantly discovering new things.

Personally, when I engage with AI, I find myself deeply in my challenge zone, often reaching a state of flow. Given your expertise and success, do you still find yourself challenged when creating art? Does this challenge help you achieve a flow state? If not, how do you continue to find motivation and interest in your work? Is it the challenge that keeps you engaged, or are there other factors?

Roope Rainisto: Improving upon previous work is a challenge all artists face. Every piece sets a new baseline, pushing us to surpass it. For instance, creating art like 'Life in Western America' and 'The Revolt,' which are successful on their own, raises the question: how can we do even better? This drive forces us to enhance our technical skills, curatorial approaches, and the complexities within our art.

Regarding the 'hundred thousand photos' project, breaking it down helps manage the workload—about 500 pictures a day over six months. It requires immense focus, contrary to the common belief that AI art is simple. Creating impactful AI art is one of the hardest tasks I've faced. It demands precise control to produce something genuinely personal and emotive.

People often underestimate the difficulty of AI art, questioning why, if it's so easy, there isn't an abundance of outstanding AI artworks that deeply move viewers. As AI tools evolve, it remains to be seen whether they will be able to autonomously generate art that resonates emotionally. For now, the role of the artist is crucial, as current AI technologies cannot substitute the artist's touch in creating meaningful connections through art.

Jon Wubbushi: How much does working with a curator who actually is doing a secondary curation make them more of an artist than a normal curator might be for a photographer? The second part of the question is, how do Punks relate to the feelings you're trying to do with this collection? And also, what was the conversation with Punks and your creation team, and can you talk about what you guys talked about?

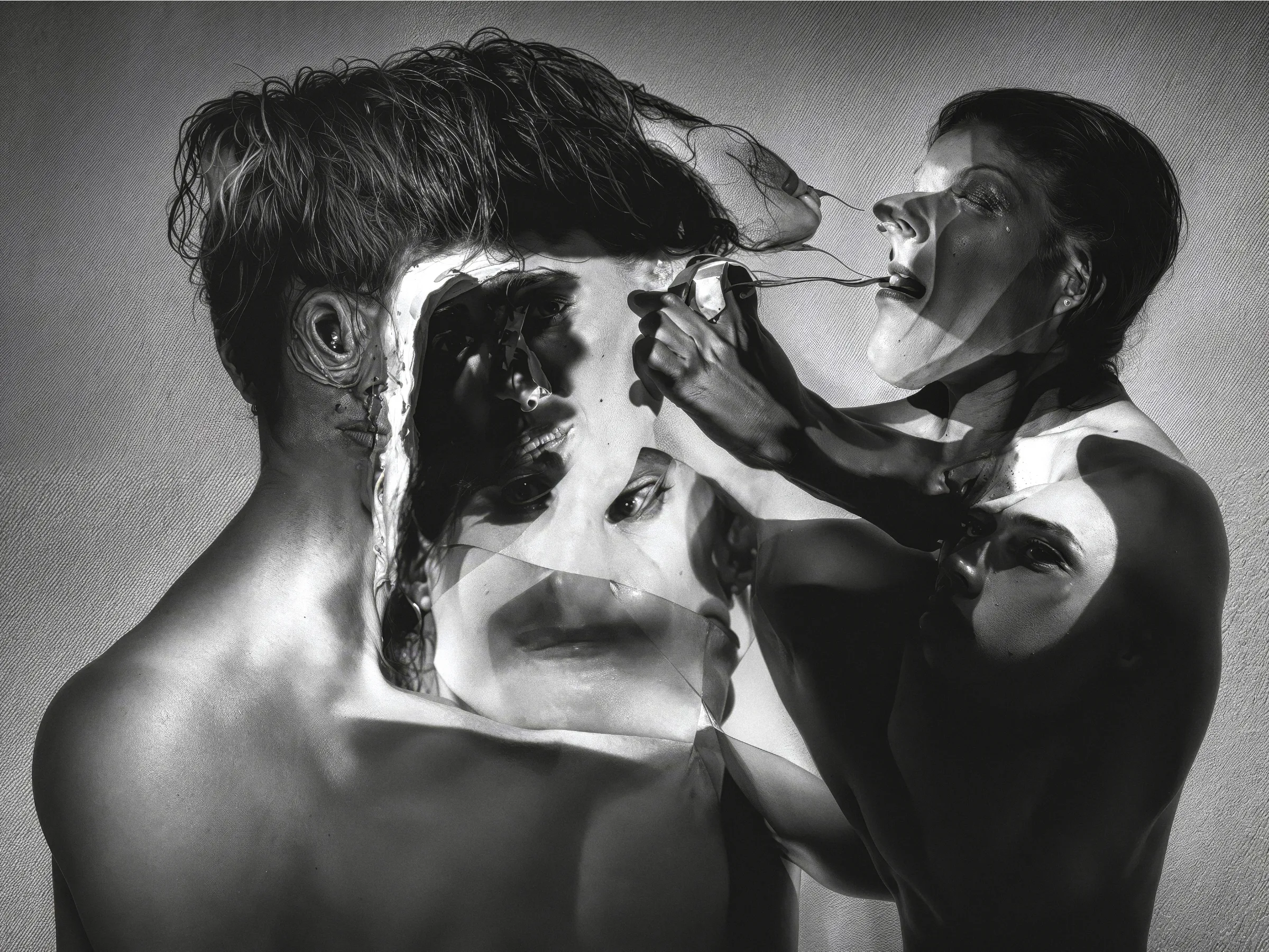

Roope Rainisto: Starting with the latter part of your question for clarity, 'Vacation' comprises 500 art pieces, of which 25 are designated as 'Punks'. These Punks fit within the broader theme of Vacation yet diverge towards the more intense end of the emotional spectrum. Typically, they present intimate close-ups of individuals, conveying strong emotions, unlike the more general overviews found in most of the collection. We hypothesized that there's a specific type of collector drawn to these Punks, who may be looking for something more profound compared to other pieces in the collection.

Introducing these distinct segments helps prevent redundancy and maintains excitement within the series. When creating such a large volume of work, the challenge significantly multiplies; producing 500 pieces isn't just five times harder than 100—it's exponentially more complex. This complexity arises from the need to keep each piece fresh and unique without repeating themes or emotions. The Punks add a special 'spice' to the collection, enhancing its diversity and appeal.

I apologize, but I've forgotten the first part of your three-part question.

Jon Wubbushi: I'm intrigued by the unique 'spice' you mentioned in the Vacation, and I'm curious about the emotions it intends to evoke. Pushing further, what made Life In West America remarkably successful was its boldness—it introduced a completely new visual language that was almost unfathomable at the time. Your work consistently challenges conventional boundaries, which is evident when someone first encounters your collections; it takes a moment to grasp the depth and intent.

Considering your mention of the Punks aiming to cater to a specific type of collector, it seems Vacation might be somewhat tailored to meet collector expectations. Previously, you hinted at this approach in another interview. To what extent do you feel this collection is about giving collectors what they want, and how do you reconcile this with your artistic vision?

Roope Rainisto: That’s a very pertinent question, one that I frequently grapple with. As an artist gains recognition, the majority of requests start to centre around their established style. For example, private collectors and institutions often ask for works that resemble previous successes. This is similar to how a band like Radiohead might be expected to replicate the success of a hit album.

Navigating this landscape is challenging. At the beginning of this year, I launched Smile, which marked a departure from my usual style, resulting in a mix of interest and confusion from my audience. It illustrates the dilemma of trying to satisfy fan expectations while also pushing artistic boundaries.

My approach has been to attempt a balance—giving people what they want while striving for genuine artistic growth. However, there’s a risk of overthinking and becoming too strategic, which can detract from the authenticity of the art. The pressure to conform to expectations might lead artists to plan their creations too meticulously, which isn’t always conducive to genuine creativity.

Ultimately, I believe the best art comes from artists addressing their own 'itches'—their personal creative impulses. For me, whether it was exploring themes like smiling or vacations, these were genuine interests that drove my projects. Still, it’s a complex issue without a clear-cut answer, and it’s something I continually navigate as I develop my work.

Jon Wubbushi: One thing I've noticed with your latest collection is the evolution of your tech stack. Previously, you've described AI art as a function of space and time, emphasizing that even with the same technologies, the results inevitably change due to updates in the underlying systems. You mentioned that it's impossible to recreate earlier works like Life In West America exactly because of these changes.

For this collection, you've continued to use Stable Diffusion, version 1.5, and similar training models, yet there are noticeable differences, such as the inclusion of very modern elements like a black lady with a contemporary hairstyle. It seems there are more modern-looking subjects in this series.

Could these changes be attributed to advancements in upscaling technology? How has this affected your process of image selection? Has the new technology allowed you to expand your artistic choices in any significant ways?

Roope Rainisto: Indeed, the use of new technology in my latest collection is quite significant. For the first time, I've incorporated Stable Diffusion XL, which accounts for about 50% of the artworks. Alongside this, I've also begun using AI upscaling techniques. Both are firsts for me and have introduced a new layer of seeming realism to the pieces. Interestingly, the small details appear highly realistic due to the upscaling, yet the overall picture retains a sense of unreality.

Viewing the progression of my work over the past six months in Lightroom, sorted by time, clearly shows how the integration of these new tools has evolved. It's fascinating to see the collection capture the state of technology at each moment. This period in AI reminds me of the early days of synthesizers, which had a unique sound that people now pay a premium to replicate.

I ponder whether, decades from now, people might seek out the 'old' AI technologies for their distinctive qualities, much like vintage synthesizers. It's a fleeting moment in the evolution of AI tools, and creating art now captures this unique snapshot in time. I hope that years from now, looking back at this collection will remind us of this specific phase in AI's development.

Jon Wubbushi: When you created Life In West America, you mentioned drawing inspiration from Robert Frank’s 'The Americans.' Is this new collection similarly inspired by a particular photo book, or is it a continuation of that theme? Additionally, regarding the ethics of AI art creation, you've previously commented on avoiding the use of 'in the style of' in your prompts, as it tends to result in less engaging art. Do you also see ethical implications with this approach? Specifically, did you use Robert Frank’s images to train the AI for Life In West America, and how do you navigate issues of authorship when incorporating influences from other artists?

Roope Rainisto: No, I didn't train the AI specifically on Robert Frank's images for Life In West America. Frank's work is primarily in black and white, which isn’t suitable as training material for the colour themes in my projects. It’s important to note that tools like Stable Diffusion are already trained on a vast dataset of about 5 billion images from the internet, encompassing works by many famous artists from the past century. This means that an artist doesn’t need to train the AI on specific individuals; the breadth of human artistic output is already embedded within the AI.

Regarding custom training, it's more about setting a certain visual style rather than replicating specific artists. This fine-tuning adjusts how the AI generates outputs—either enhancing certain styles or intentionally introducing glitches for more unique results.

On the topic of authorship and ethics, using phrases like 'in the style of' doesn't necessarily breach ethical boundaries, but it does raise questions about the originality and quality of the art produced. I avoid using such specific attributions because they tend to constrain the AI's creative potential. My aim is to produce art that doesn’t mimic a particular artist but instead represents a diverse amalgamation of influences, reflecting the vast training dataset. This approach strives to capture a broader artistic essence rather than replicate identifiable styles.

Jon Wubbushi: I want to push you a little bit more to get that ethical yes or no, though. Not good or bad. Do you think ‘in the style of artists’ inputs are ethical?

Roope Rainisto: I believe that for many new artists, beginning by imitating the styles of those they admire—like a new punk band emulating Green Day—is a natural part of the learning process. This initial phase of replication helps artists understand the art they love and is often a necessary step towards finding their own unique voice. Over time, most artists realise that mere imitation isn't fulfilling; it's more of a pastiche and doesn't represent their true creative potential.

It's important not to dismiss this stage as merely a 'necessary evil.' Instead, it should be seen as a crucial period of self-discovery and growth. Artists eventually add their own twists and develop distinct styles as they evolve beyond their initial influences.

This phenomenon isn't limited to AI artists—it's a universal aspect of artistic development. Beginning by 'playing in the style of' can serve as an homage, reminding us of and redirecting attention back to the original artists. Therefore, I don't view this stage as a major ethical issue. Instead, it can promote appreciation for the original artists, especially if their influence is recognizable, leading audiences back to the source of inspiration.

Jon Wubbushi: Super insightful, interesting answer. Holly, would you like to take it from here?

Holly: Yes, of course. So you were speaking the other day about how you imagine that in the future there'll be works that are 10% AI, 20% AI, 30%, the whole way across the spectrum. How do you think that that will affect the perception of authorship being an ethical issue? How do you think that that will affect the conversation around authorship and AI? And do you think that will affect your own work in any way?

Roope Rainisto: Recently, we discussed how people often categorize art as either entirely AI-generated or not at all. However, I believe that within a few years, AI tools will be so integrated into standard creative software like Photoshop that the line between AI and non-AI art will blur. This integration will likely lead to artworks being partially created by AI, maybe 10% or 20%, raising new questions about authorship.

This scenario mirrors the initial reactions to Photoshop two decades ago. Initially, there was debate about whether using Photoshop still constituted 'real' art. Now, it's universally accepted as just another tool in an artist's kit. Similarly, AI will become just another facet of the creative process, eventually integrated and possibly rebranded under more neutral terms like 'context-sensitive fill.'

Regarding the consumption of art, most people don't need to know or care about the tools used to create a piece; they are more concerned with the emotional impact of the artwork. As AI becomes more commonplace, artists will need to enhance their skills to stand out. Just as the proliferation of cameras didn't kill photography but instead pushed photographers to innovate and refine their craft, the widespread use of AI in art won't spell the end of artistry. Instead, it will challenge artists to find new ways to engage and move their audience.

Roope Rainisto

Roope Rainisto is a Finnish artist, designer, and photographer with a passion for storytelling. His work explores the boundaries between the real and the virtual.

He has worked for 25 years as a creative professional, now pioneering innovative applications of AI-based generative methods for post-photographic expression. He earned a Masters of Science in Information Networks from Helsinki...

Jon Wubbushi

Wubbushi explores the depths of the human psyche, delving into the complexities of emotion, trauma, and the collective unconscious. Drawing from his own experiences with generational dissociation, Wubbushi creates visual echoes of a fictional past that hauntingly blur the boundaries between the real and the surreal.

Using a meticulous approach to generative AI image making, Wubbushi combines the...