Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

The Art of Doing Nothing: The Concept and Creation of NullMachines

Mimi Nguyen (MN): I'm fascinated by how you've both built up very consistent practices. When you look at Loïc's work, you know it's his, and the same goes for Kerim's. I love how we can identify your styles - it's like a museum game, trying to guess the artist. It's great to see both of you in this collaboration. I couldn't imagine a better pairing for this collaboration when Kerim mentioned Loïc. Kerim, I believe your background is in music. You mentioned you were doing a lot with music previously. How did you end up in digital art?

Kerim Safa (KS): Yes, my background is indeed in music. I studied music, but before that, I also studied fine arts. For me, visuals and music have always gone hand in hand, though music was the focus for a long time.

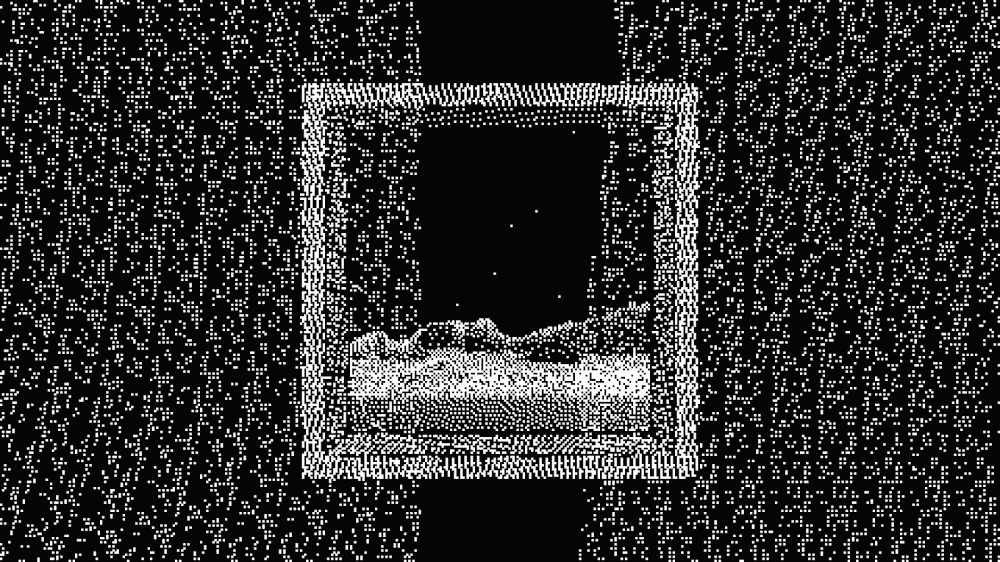

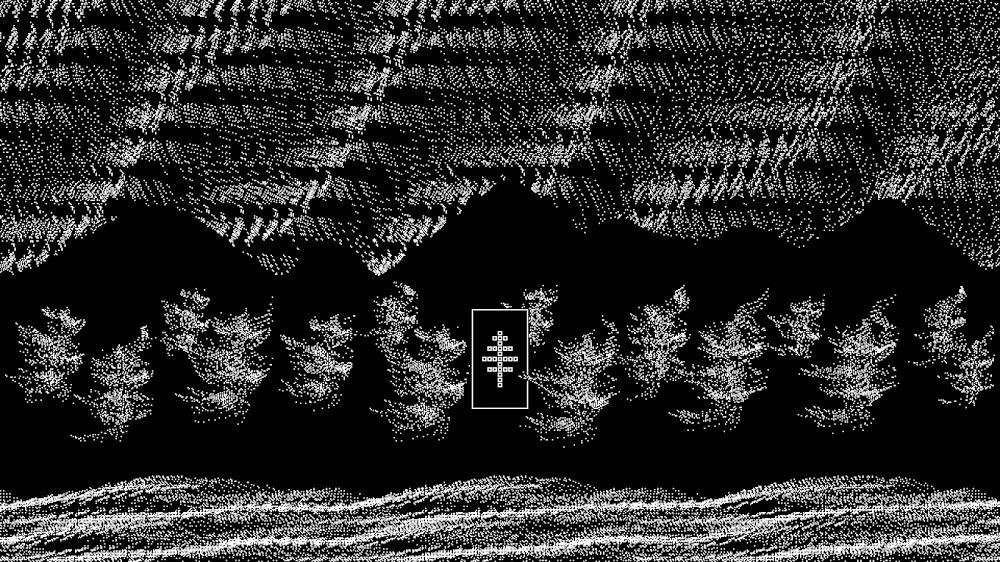

Over the past five years or so, I've transitioned to focusing on visuals. My current practice involves creating animations characterized by chunky pixels and strictly limited color palettes. Sometimes audio is still involved, but now it plays a secondary, accompanying role.

When I was performing live, I'd create my own visuals or audio-reactive works and installations. But lately, especially since COVID, I'm not performing as much. Right now, I'm playing bass in a band, which is quite different.

Before that, I was more into performing with synthesizers and audio programming. I had generated music projects that I programmed in Max MSP and Pure Data. It evolved from a technology-oriented music practice into something more simple and intuitive, like creating animations by drawing pixels on the screen.

There was a shift where I wanted to seek something more pure and intuitive, similar to drawing or playing a conventional instrument. It's a different approach from programming - you're using a different part of your brain. So that led me to work with pixels, strictly drawing by hand, and creating animations in an old-school way.

MN: You've gone from mixing paint colors to working with just black and white pixels. How did this evolution happen?

KS: Looking back, I wasn't really conscious of these decisions, especially when switching between disciplines. I should mention that I also worked in the game industry for a while. Living in Istanbul, I needed to work because being an artist in Turkey is challenging if you want to survive.

This experience opened up new possibilities in my mind. It was part of a constant search for something, following what attracted me. It's super fun when you're in your twenties or early thirties, but at some point, I felt a bit lost.

I felt I needed some agency, and that's where I settled on pixels. It's something that's been with me since childhood - the games I played, the aesthetics I liked, and my relationship with computers. Everything came together in that sense.

Working strictly with black and white didn't happen immediately. I've been doing it for the last couple of years because I was searching for what I really wanted in the creative experience. When you reduce it to the core, it's similar to my experience with music - I like to focus on one instrument and create something beautiful within its limitations.

I also appreciate the grid system and the binary nature of black and white pixels. It's adaptable to many things, even in physical space. I found that working with these minimal materials allows me to reach a certain depth that makes me happier and more satisfied with the results. It's about the personal excitement of the process.

MN: That quest for simplicity is fascinating. You're minimalizing the available media, even in playing bass with fewer strings. Loïc, I know you come from an academic background in maths - but how have you developed your distinctive artistic style?

Loïc Schwaller (LS): I think my style is a combination of my background in math and other influences like video games, as Kerim mentioned. I played a lot as a kid and still do. Pixel art made a big impression on me as a teenager, so that's something I've carried with me until now. It's a significant part of where my style comes from.

Interestingly, I started experimenting with dithering just before getting into the web3 space. I think I began experimenting with it around the end of 2020 or early 2021. Now my practice is intertwined with dithering, which I really appreciate. It wasn't always the case, so it's fascinating to witness this evolution.

MN: And how did you guys meet?

LS: I think we met in a gallery in Amsterdam once at an open gallery.

KS: Even before! Through our common friend came to Amsterdam. We were in separate contact with him, and then he invited us. I also invited Loïc and Kirill, and that was actually the first time.

LS: Ah yes, we actually met through Matheus Leston. We had a couple of drinks together, and it was really fun. Then I think we saw each other again at the DEMO festival, which is a big motion design festival organized by a studio in the Netherlands. They take over all the ad screens in the country for 24 hours, and Kerim and I both had pieces selected for this event. We met at the central station to run around and find our pieces on the screens, which was also very fun.

MN: It must have been super impressive. I hope you guys are coming back, or it's going to be an annual event so I'll have an excuse to go to the festival and see that. It's very impressive to see your work on a bigger screen.

When you guys met, how did you come up with the idea of collaborating in this space? From my perspective, I was speaking to Kerim last year about an exhibition in Manchester. It was with Kerim Safa, Gretta Louw, Kristen Roos, and Leander Herzog on a massive screen - basically on a skyscraper, which was amazing to see. It was super stressful for everyone because they had to create a dedicated piece for the screen itself, more site-specific.

Then for the release, we dreamed about how this could be generative. I personally had no clue, and Kerim was telling me there could be an option. He was thinking about it and had something in mind, but kept it as a secret.

KS: Turning the machines into generative artworks was something on my mind for a long time. We talked about it with you as well, but I remember the exact moment it came together. It's actually funny, and funnily documented.

We were both at the NFT Show Europe in Valencia last year. I had a piece there called "Factory of Nothing," which was about machines. We were in front of it, talking, and by that time we had already been friends and attending exhibitions together. Something was already developing. We both had similar interests from the start, and it was obvious. We talked about doing something together, but it wasn't clear what until Valencia. The idea emerged when we were discussing the piece, thinking about how we could do this and convert it into something different.

LS: That's when I screamed "Wave Function Collapse!"

KS: Yeah, you were already working on it or thinking about it, I'm not sure.

LS: I wanted to work with it. That's an algorithm I wanted to use for a very long time. So when you mentioned it, I thought, "Yeah, I know exactly how to do that."

KS: Previously, I had made some tests using physics engines or independent elements in the machines, but it didn't work as I wanted it to. I never kept my motivation up until we spoke and you mentioned Wave Function Collapse. It all came together exactly one year ago, and for a while, we didn't do anything. I think you sent me an example of a test with Wave Function Collapse without visuals.

LS: It was around October or November last year. Just little cubes going on some kind of minimal tracks. It was just a proof of concept, basically.

KS: Exactly. And then I sent a few examples as tiles, just some cubes going from one place to another, really simple. Then we implemented the visuals, and we saw it working immediately. After that, things took off.

MN: I know we post that it's generative, but it's also handmade because there are elements that Kerim is doing by hand. Then you're adding the algorithm.

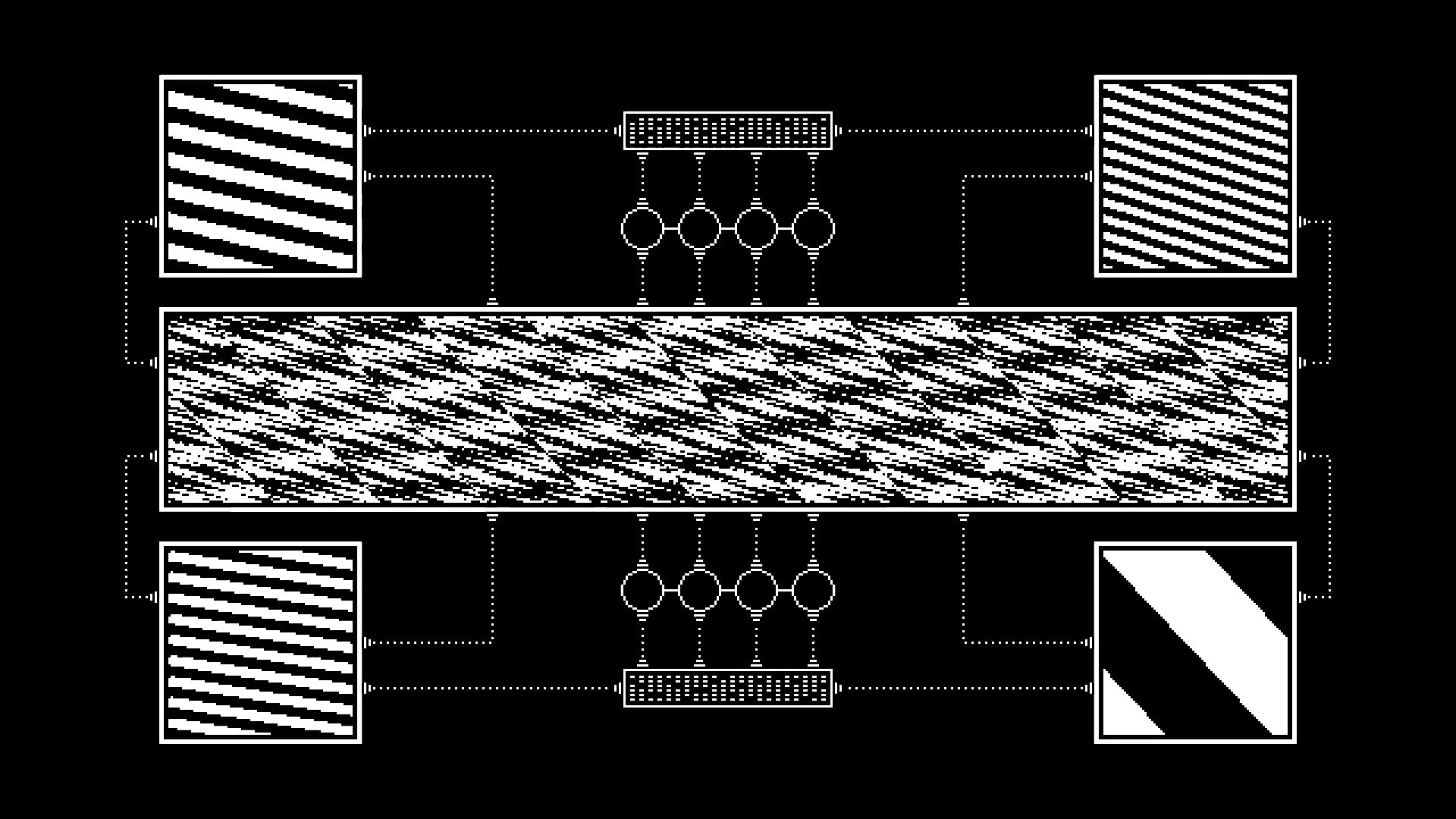

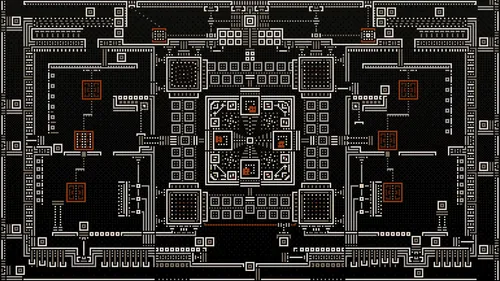

LS: This project includes both handmade and creative coding generative elements. The way the machines are built is by stitching together hand-drawn tiles that Kerim made by placing pixels by hand. We have little 30 by 30 pixel tiles that we stitch together with an algorithm called Wave Function Collapse. This algorithm is just a fancy way of saying that you choose a tile in your grid, then look at which tiles can go next to it, choose one, and continue iteratively.

In the end, you have a machine, just like you'd fill up a Sudoku grid. You find the cell in your grid that has the least options, choose one, and then see what this choice means for your grid. You propagate the consequences of your choice, and continue until you've solved your grid.

When building a nullMachine, we do the same with tiles. We had 144 drawn tiles in the end, and these can be rotated and mirrored, giving us more than 500 options in the machine. That's how the machines are built. For me, it's generative because as soon as part of the process is generative, the whole thing is generative. If there's an autonomous system involved in the process, it's generative. It doesn't have to be fully generative to be considered generative. So it's both handmade and

generative, which I find really cool.

MN: How did you stitch them so they are continuous? They loop around without getting stuck at the edges, managing to complete the entire route around the artwork without breaking. The stitching seems very complex. It's like Jared Tarbell, who we had a Twitter space with last week. He's obsessed with the maze concept, trying to find the fastest route and different mathematical combinations of things.

What I find really fascinating here is that you took 144 handmade elements that Kerim created and compiled them into various branches that move continuously. How is that even possible?

LS: So each element is accompanied by a description. For instance, for each tile, we specify where the cube is entering and exiting the animation. We have three different positions on each edge that can be used.

For the top edge, for example, you have left, center, and right. The cube can only enter in one of these three positions. Then it can exit on any of the other edges, at one of the three different positions. If you describe these positions, you can give a set of rules to the algorithm saying that if you have a tile with a cube exiting on the top right position, it needs to place a tile next to it that has a cube entering on the left side at the top position.

If you give the algorithm all these rules, it can do that because it's completely mechanical. Once you have the rules, it's easy to know which tile you can place next to the one you just put - you just have to look at the edges to see if they're compatible.

The tricky part was that because we're using animations, we had to make sure that the cubes are entering and exiting at exactly the same time. That's something Kerim had to take care of when he was drawing the tiles. He had to make them pixel perfect, and he did an amazing job because everything worked from the get-go.

MN: I recently watched the video from Manchester where Kerim designed for five screens on the building. He created the machines to enter from the left screen, go to the center, down to the main screen, and even underneath the building. It's fascinating how you could follow one cube traveling around the whole building.

I wanted to ask about the concept of nullMachines, and it's quite cheeky because you made this amazing trailer about doing nothing. Can you talk us through this?

KS: From the beginning, that was something we'd been talking about. The machines were designed to basically do nothing. It was an ongoing concept even before we started this project. At first, we didn't have a title or a fully formed concept, just ideas about how the machines would work technically.

I think the turning point was when we were discussing the project and someone suggested adding text to the screens. That idea shifted the whole theme.

LS: I think that's when the actual narrative was born.

KS: Exactly. We started joking around with slogans, like those cheeky ones from Apple commercials. Suddenly, it all made sense because we were designing things that do nothing. It became a commentary on consumerism and tech worship. It slowly turned into something really fun for us. I think this is one of the most enjoyable creative processes I've been involved in.

LS: It's been a fun project to work on.

KS: Definitely. This was almost the last step because when we were talking about the generative part, there are multiple layers. There's the layer of the machines, the boxes moving around, which are like traditional animations. But there are also screens that display real-time graphics. So it's a really nice blend of both worlds, with code-based graphics on the screens.

LS: I think this was only possible because our aesthetics are so compatible. Even though we have different working methods, we share a lot in terms of aesthetic sense. It made sense to blend them. Your little cubes, the little screens, the abstract gradients, the pixel blinking - it all just works together.

KS: Yeah, and accepting the idea of using text and cheeky self- advertising with the machines - it allowed us to go crazy technically but also have fun conceptually, blending it into a bigger narrative. We even created a 50s-style commercial that's super enthusiastic about what we're selling. I used some archival footage from the 40s to 60s, which became part of the project itself. It has its own kind of humor and aesthetics that fit well with the project.

I think if one of us were doing this as a solo project, we wouldn't have gone this far with the narrative. The feedback and pushing each other resulted in something very tongue-in-cheek and cheeky. I'm really glad we collaborated on this.

MN: You've really come back to the core of why we're all in this space - for digital art that we personally enjoy, not because someone told us to like it.

I love that this is an open edition, not meant for flipping. It's for everyone to have fun and enjoy. I hope this series will be something people want to keep and play with, like each person having their own unique piece of a machine.

LS: We have the nullMachines++. It's just a bigger machine that does even less, still nothing.

KS: That was kind of an excuse for us to test the bigger version. We're actually testing different sizes and have some ideas for real-life exhibitions. I love seeing the outputs from people - it's amazing. We've generated hundreds of these, and we're still excited by them.

LS: And it pushes the concept of nullMachines further. Like how big brands always have a "pro" or "plus" version, we needed a Plus Plus Plus version to keep the narrative going.

These were only possible because we implemented the Wave Function Collapse algorithm efficiently. The first version wasn't as efficient, and even the normal nullMachines were taking almost 10 times longer to render initially.

KS: We needed to optimize a lot. Loïc made some changes to the code that really improved efficiency. It's mind-blowing how much is going on technically under the hood, yet the narrative doesn't take itself too seriously. It balances the whole project, I think.

LS: I agree. It's all fun, but we had to do a lot of work. It's a labor of

love.

MN: It's fantastic how this works as a piece to live with at home. It's not like video works that might get boring after looping. This just works really well in a room, and I've enjoyed living with it these past few days. It's a piece that fits both as a response to what's happening with the market and the consumption of digital art, but it could also expand into commentary on labor and machine work. I hope many collectors will keep one for themselves and live with it.

It's been almost a year of work, and I'm really happy and grateful to be a part of it. I hope to see it again on a massive screen like in Manchester, and that it will travel to exhibition spaces and people's homes.

KS & LS: We're really glad we started this collaboration and we'll definitely continue working together.

Kerim Safa

Kerim Safa (b. 1985) is a Netherlands-based artist working with pixels and sounds. His exploration revolves around ideas related to systems, perpetuity, perception, and representations. Safa's practice finds primary inspiration in early abstract animations and computer games, incorporating pixel aesthetics, frame-by-frame animation techniques, and a limited color palette. His artworks often...

loackme

loackme is a French generative artist currently based in Amsterdam.

After completing his PhD in Statistics and working as a researcher for some time, he made the decision to leave academia in 2018 and pursue his passion for digital art and graphic design. loackme's artistic practice is characterised by his love for monochrome and geometric designs, as well as animated loops.

Amongst other...

Nguyen Wahed

Nguyen Wahed is a New York-based gallery with a program that focuses on, but is not limited to, digital and generative art practices. Focusing on contemporary artists (Leander Herzog, Sofia Crespo) who embody the intersection of technology and creativity, it expands onto rediscovering select phenomena in the peripheries of digital art starting from the 1960s (Manfred Mohr) to the first...