Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Stuart Batchelor on his Love for Imperfections

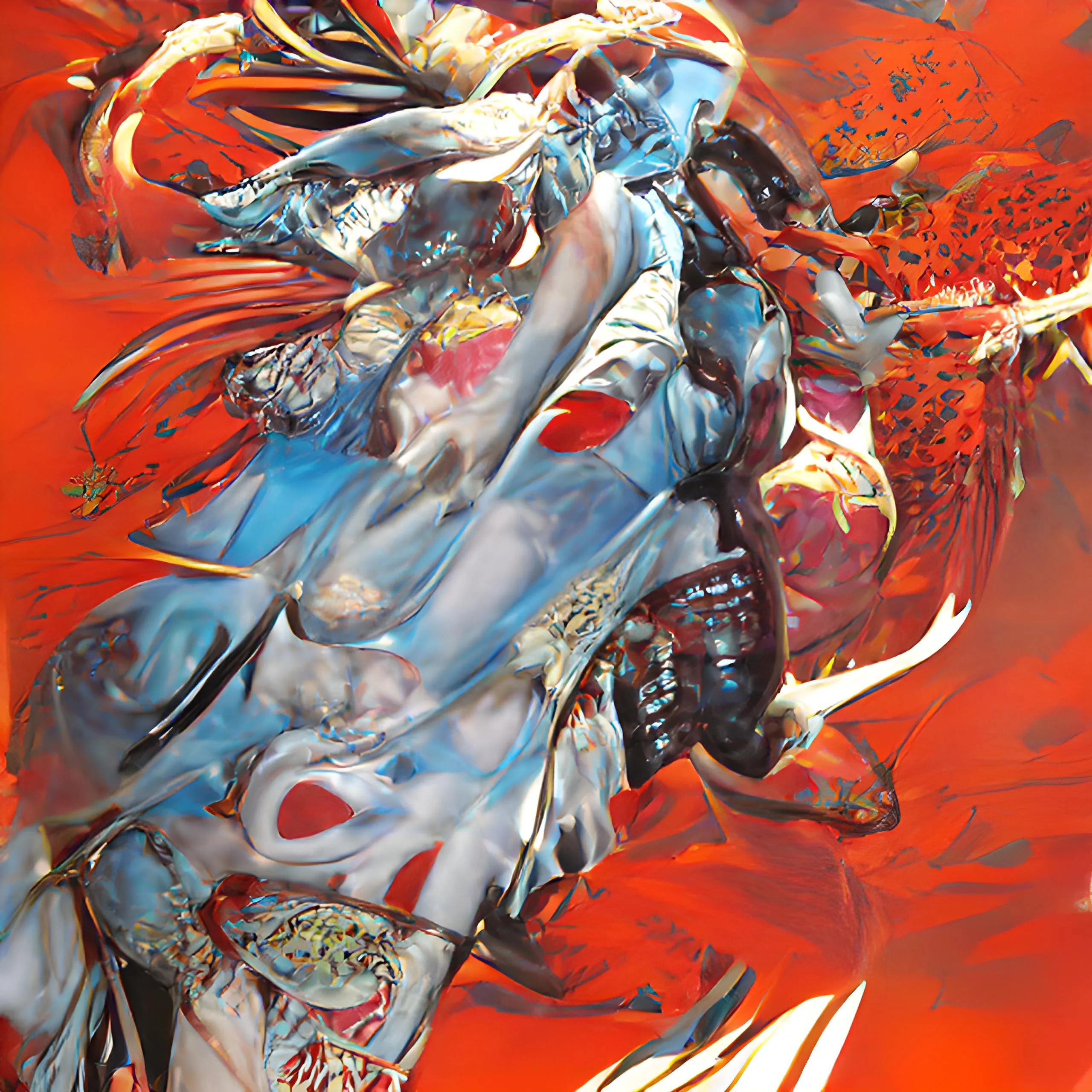

Imperfection(s) is the theme of the wider exhibition and a prominent aspect of your series. Imperfection – or the acceptance of imperfection – is a theme also present in your previous series. You have written before that a lot of the generative art field is driven by ‘happy accidents’, and you say this series inverts a trend of generative art – namely ‘imperfect detailing’ – to instead use ‘perfect detailing to make an imperfect whole’. Could you expand on what you mean by this, as well as your interest in imperfection?

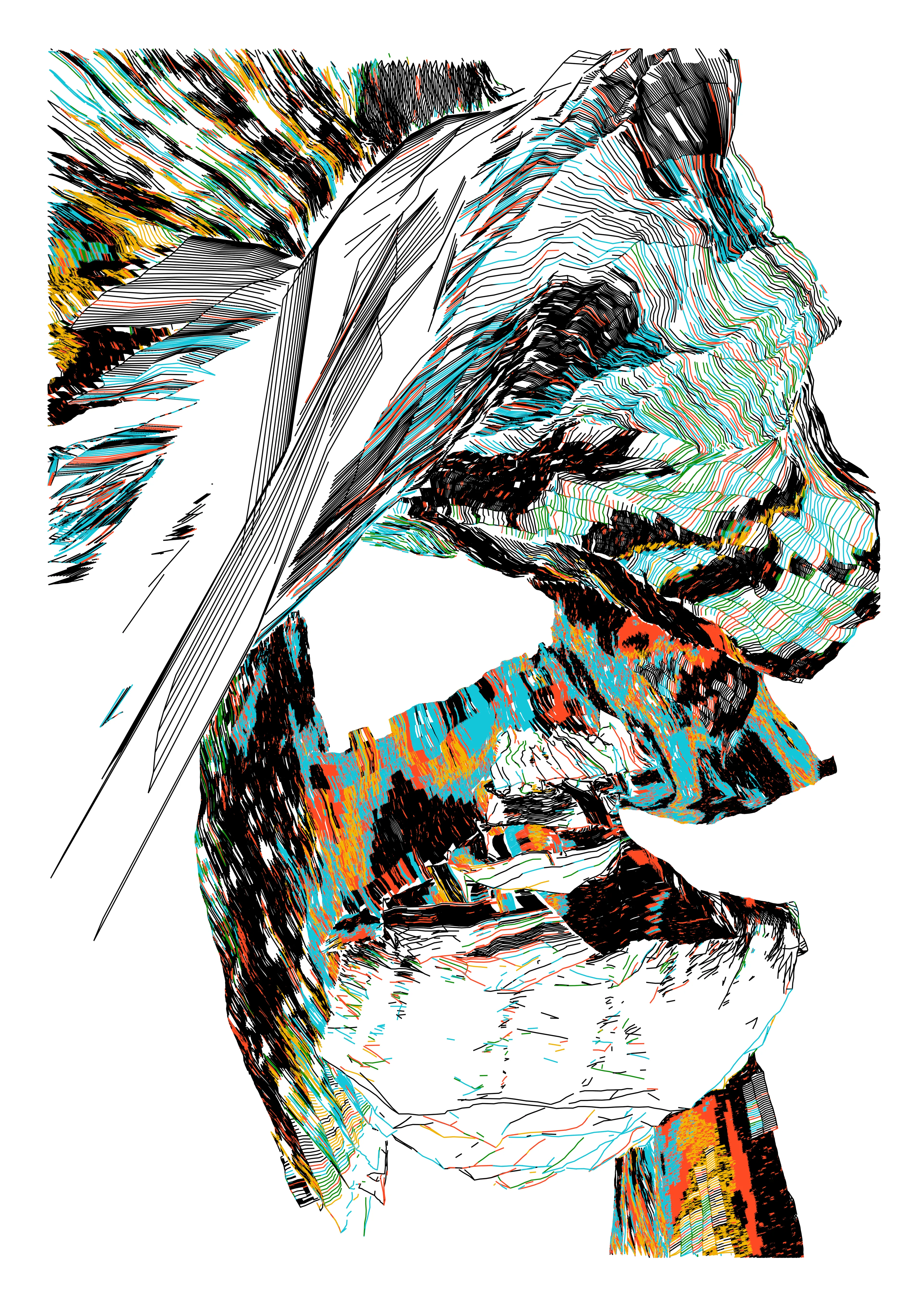

I’ve always been more interested in the imperfect things. Going back to when I was a child, I’d love muddy shoes, broken toys, impasto paint. I try and use my work to explore these fascinations I’ve always had. The more I’ve investigated the imperfect, the more I peel away at the underlying meaning, beyond just its aesthetics. It’s a love of broken things, of things that have perhaps been discarded, things that have been through the wringer of life and come out the other side. I like to elevate that debris and give it the reverence I see in it.

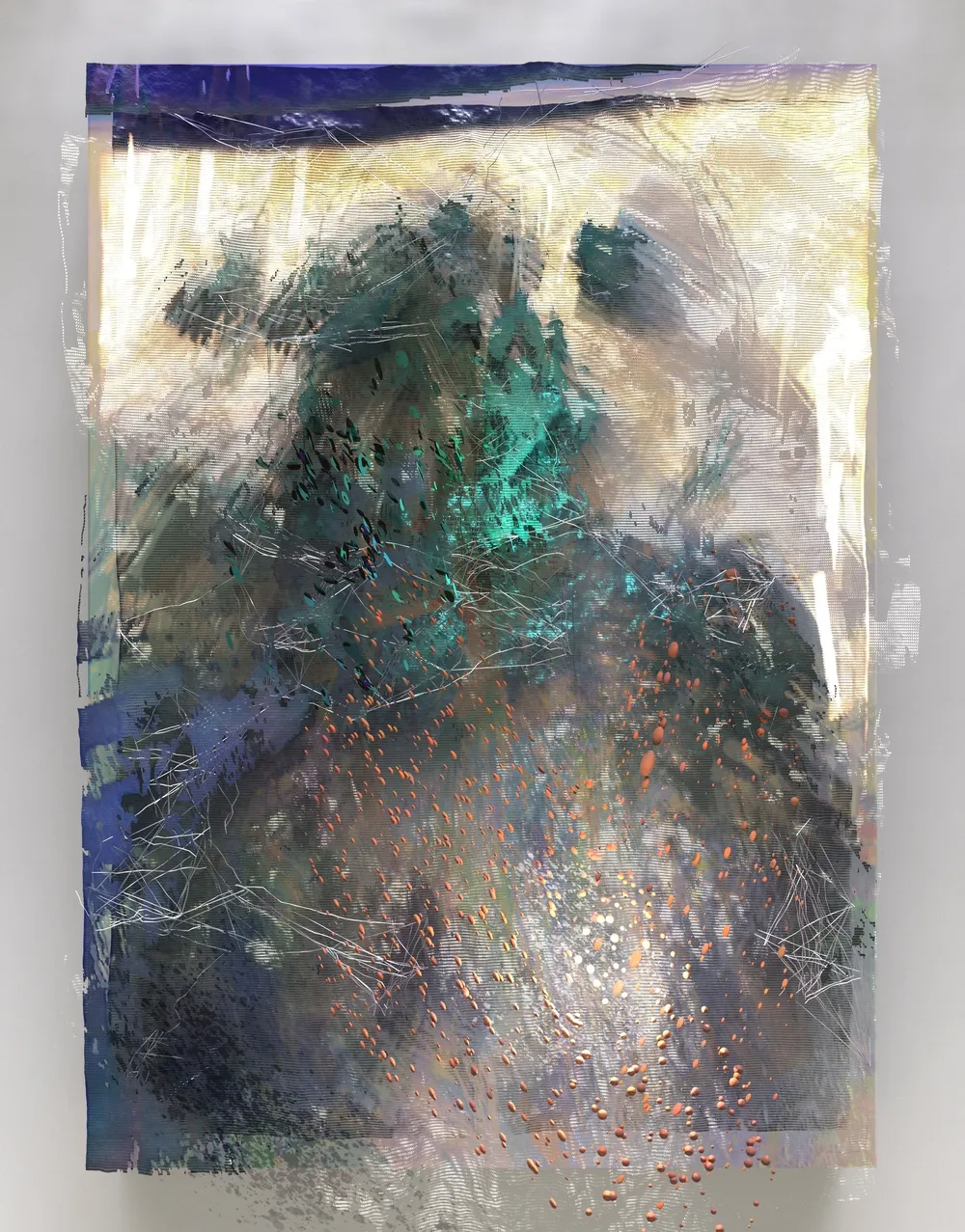

There is a motif in generative art to replicate the nuance and imperfection of physical media. I love this and think our collective fascination with it runs deeper than just the desire to emulate what is familiar to us. I see it as an extension of abstract art, where now the subject is the media itself. To me artwork that does this is saying ‘look at these properties we take for granted, now look at how we can distort them’. I think some of the best generative art right now threads this needle between familiar and unfamiliar. Creating a new kind of media that has never been seen before and isn’t physically reproducible.

To me, imperfection is perfection. So in Möbius I wanted to represent that. I invert the scale at which the imperfection is noticeable. Instead of building a perfect macro effect from afar with imperfect micro dots and lines I wanted to create a dirty, natural effect that on close inspection was composed of clean sharp details. I was originally going to go further than this, making the details also nuanced and imperfect but one of the ‘happy accidents’ during development was that I noticed the piece didn’t need it. It was achieving the level of chaos and dirt I intended and doing so in a way I thought was fascinating.

You have described the balance between planning and improvisation in your approach as ‘someplace further than blind playing would lead, and someplace more spontaneous and unanticipated than a rigid design implemented generatively’. Was this the same for Möbius? Please could you give an overview of how you created this series?

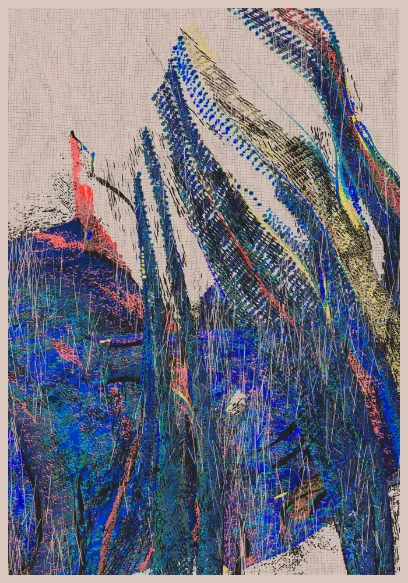

The process in Möbius I think is a perfect example of an idea I try and build on in each of my projects. Automatism, a term used primarily in psychology, which describes bodily movements that are not consciously controlled like breathing or sleepwalking. I aim to build systems that are an extension of human gesture, injecting my own instincts into the process and the mark making.

During development, as the piece is being painted in front of my eyes I will be marking where the next stroke will go, with no agenda I am conscious of. The system will then paint the next stroke and we are either in agreement or disagreement. If I disagree with what the system did, I will then sculpt the code towards the mark I would’ve liked to see. If we are in agreement, the system becomes an extension of my own automatism, gesture and instinct. The really interesting thing though is when we initially disagree, when the tool I am creating puts a mark in a place I wasn’t expecting and yet I still find compelling. In this instance what does the system represent? It is no longer just an extension of me but perhaps some mixture between myself and the boundaries of the algorithm? Tool and creator combine and the line between them blur. It amplifies my dreaming and I humanise its processes.

For me, Möbius evokes associations with modernist art and conveys weave-like textures really nicely. You have also cited mosaics and post expressionism as influences. What other sources do you take your inspiration from?

I think at the core of it all, weaves are a large inspiration in my work. I mean that in a very abstracted sense too, as in lattices of patterns. I see them in fabrics, carpets and mosaics - which I think I owe to my Persian heritage. Seeing Persian rugs, islamic geometry and mosaics from an early age has certainly influenced my passion for rich details as well as the creativity that mathematics holds.

But I also see weaves in brushstrokes and nature. If you compress lattices enough they become indistinguishable from physical material. This is then where the influences of 20th century painters comes in. I feel with a lot of my favourite work there is both a dirt and expression held within their marks. The idea that there is a ‘soul' you can feel for these lattices fascinates me and speaks to how our subjective, emotion-based reality meets with physics and the natural world.

Again though, this is something I explore with no defined idea when I create work. It’s more accurate to say these influences have become apparent to me after the fact. It’s only when I take a step back that I see these connections in my work. I don’t go into art making with an outlook to say something. I use art to find my interests, not state them to the world. At the beginning I don’t know them and at the end they reveal a little bit more to me. Which I then continue in my next project and so on. I like art that has a deepening through an artist’s life. The same fundamental idea expressed again and again from different angles, becoming something new each time. I think we fundamentally tell the same stories we’ve told since the dawn of time, I try to use art as a drill to bore down to those perennial ideas and attempt to present them in a unique way.

You have discussed that making long form generative projects are labour intensive – what are your patterns of working, and how do you ensure you stay happy and productive?

I’d say as long as I maintain a sense of the underlying purpose of the piece, even if I can’t express it in words then I stay motivated and productive. That journey though is a love, hate thing for me. Both are useful for steering the development. Regardless of if my feelings towards my current WIP are negative or positive I try and use them constructively. I constantly vocalise, draw, document or otherwise express the reasons I’m feeling that way towards the work. This usually culminates in actionable next steps towards that uncertain endpoint. And a refocusing of that underlying purpose.

So it’s a constant pushing and pulling. Adding material to the sculpture then tearing it away. Moments of conscious thought and premeditation mixed with instinctual, impulsive acts of creation. It isn’t easy to create 1000 paintings, as you do with long form. You have to constantly balance, recalibrate, review. Because of it’s scale and real-time nature the work not only needs to look good, like you can get away with in short form works, but also needs to run well. You are essentially making an app, a piece of software that instead of performing a function or service creates an intangible, subjective art piece. So you have to bug fix not just the functionality but the aesthetics as well. That balance between expression and structure, making sure the endless outputs are equally compelling, performant and novel is no small feat.

The simple beauty of the outputs belies the system’s technical rigour. Generative artists are ingenious, daily innovators. Individuals and the movement as a whole inspires me and keeps me motivated throughout the process.

Leyla Fakhr

Leyla Fakhr is Artistic Director at Verse. After working at the Tate for 8 years, she worked as an independent curator and producer across various projects internationally. During her time at Tate she was part of the acquisition team and worked on a number of collection displays including John Akomfrah, ‘The Unfinished Conversation’ and ‘Migrations, Journeys into British Art’.

She is the editor...

Stuart Batchelor

Stuart Faromarz Batchelor is a London based computer artist. His work focuses on using technology for self expression, often around themes of nature, dreams and transformation. Utilising his background in VFX he enjoys developing tools that combine the artist’s hand with computational creativity, creating systems where artists can play with procedural rules like crayons.

Stuart has been published...