Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Mario Klingemann on 'Teratoma': An Exploration of AI and the Human Form

Mario Klingemann in conversation with Mimi Nguyen, foreword by Luba Elliott.

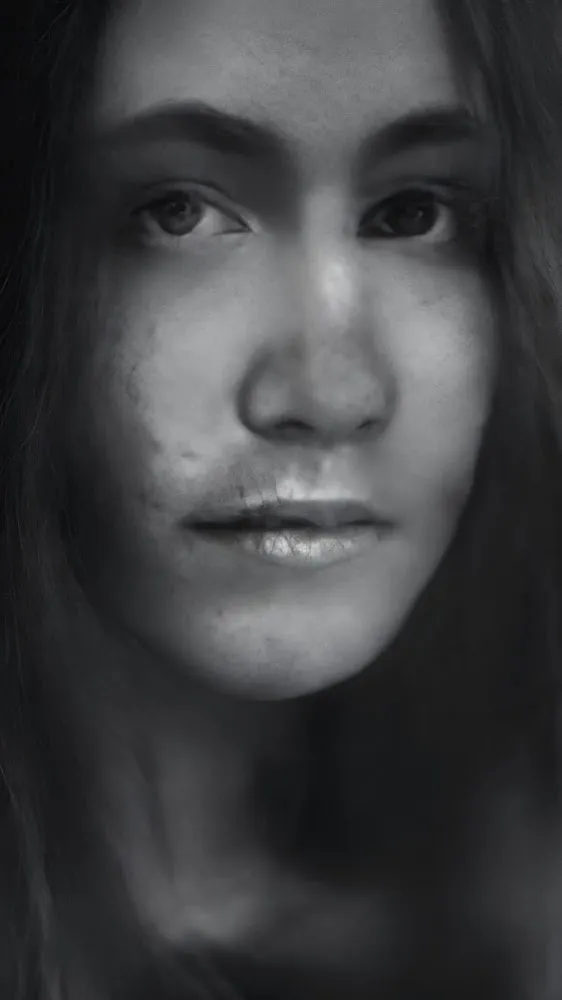

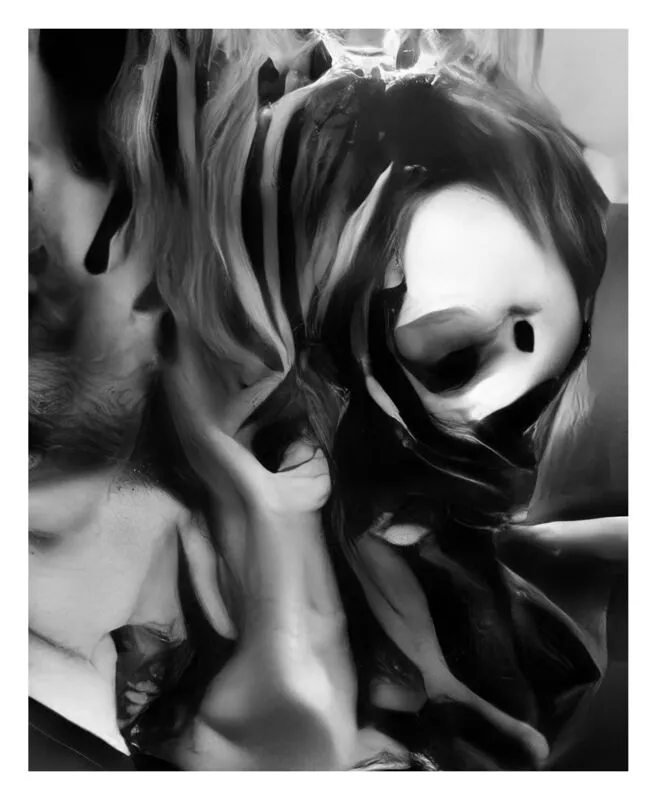

Klingemann's Teratoma series is a haunting exploration of the human form through the lens of early generative adversarial networks (GANs), AI models that the artist trained on a dataset of portraits and naked human bodies. These works are a form of ‘neurography’, a term coined by the artist to describe this form of image-making with neural networks instead of the camera. The black and white colour scheme lends the pieces a timeless quality, associating them with classical photography, whilst the GAN models used for their creation situate the works at a particular point in time in the development of AI technology. Early GAN models such as those used in this piece are known for making mistakes in their depiction of facial features, frequently misplacing the ears and eyes. Klingemann uses these to his advantage, creating an abstraction of the human face and body amongst fluid textures reminiscent of flesh, an image that takes the viewer time to assemble and comprehend. The title of Teratoma solidifies the link to the processes of the human body, drawing parallels between tumours made up of different tissues and the way GAN models process the dataset to generate images that mix up various body parts.

- Luba Elliott

Mimi Nguyen: AI - is it a tool or future artist?

Mario Klingemann: AI is an instrument. A "parascope"—an instrument of inspection—that allows us to observe and discover things which are beyond our reach, like the microscope or the telescope did before. But at the same time an instrument of creation and expression, like the piano. Can such an instrument eventually emancipate itself from its creators and become an artist itself? I do believe so, which is why I created "Botto" two years ago in order to find out. But having the technical potential to be an artist and becoming one is dependent on so many complex factors that it is still too early to tell.