Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

In Conversation with Harvey Rayner and Le Random

Leyla: For our exhibition Harvey will be presenting a generative project that he developed over the past 25 years. With this work he is redefining how we see, collect, and understand contemporary art. Yet, I'd love to kickstart the conversation with a brief overview of Le Random.

thefunnyguys: Le Random is an institution solely focused on generative arts and collects pieces from this movement while contextualising them in art history. We also strongly focus on education; we want to elevate the generative art space and tell many of the stories from the space’s history that haven't been told before.

Leyla: I find your work integral when needing to find a reference point to contextualise artists like Harvey who have grown in the digital space. It is important that we build more platforms where we can discuss but also archive artists’ works. Speaking of which, Harvey, tell us more about Quasi Dragons Studies and why now? Given that you have been working on this for more than two decades…

Harvey: I developed my "geometric meter" system in the early 2000s to structure my artistic practice and create better visual possibilities. Over 15 years, I refined and expanded upon these systems to establish my own style and language.

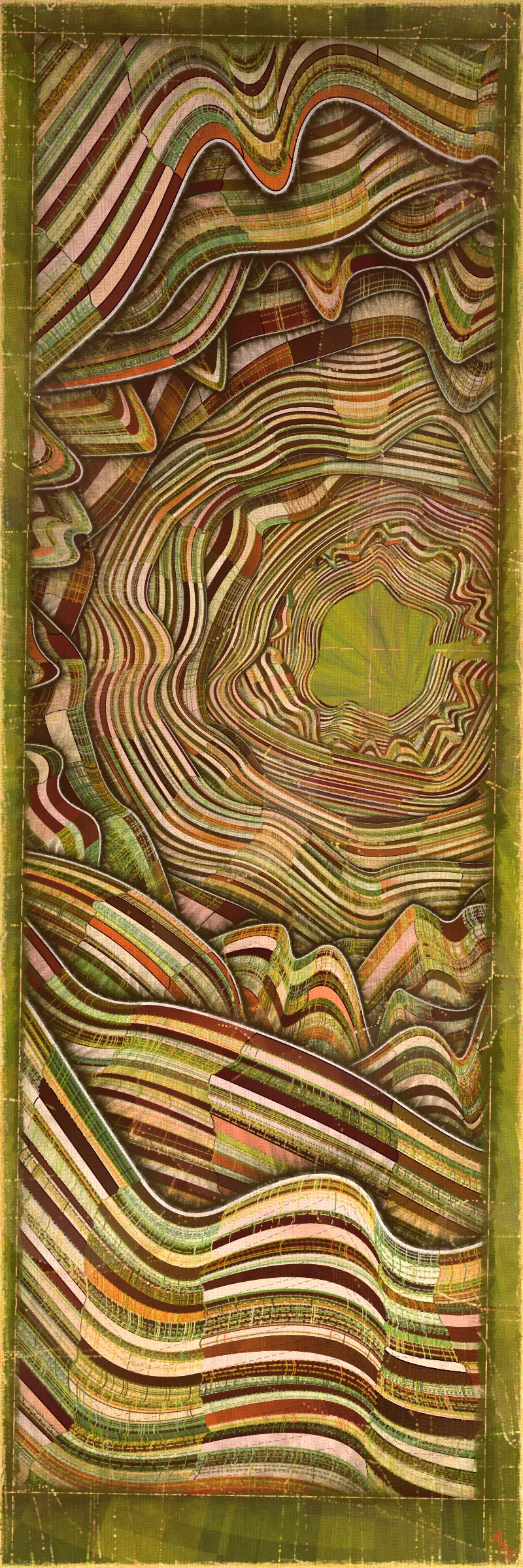

About 10 years ago, I explored generative art, NFTs, and art blocks, which felt natural for my work. My latest project, Quasi Dragon Studies, builds an algorithm to explore my aesthetic and visual language. Quasi Dragon Studies was born from the idea of when we build an algorithm and explore the aesthetic and visual language I created.

Leyla: It seems your personal life is deeply embedded within your work, and it is hard to communicate this in the digital space. Can you tell us more about this personal part of your life?

Harvey: I was not very academic, mainly because I couldn’t read until I was 18. When I learned how to read, I dived into Nietzsche’s writing; introducing myself to the world of ideas was mind blowing. Quickly after, I became interested in the world of spirituality in Buddhism, to the point I spend five hours meditating a day, every day.

I was living a strange solitude and minimalist life, I had no job or friends, and meditation gave me a way to feel seen, and I wanted to know more. I decided to go to a meditation center in America.

I landed in Toronto and hitchhiked to Rochester, New York. I slept under bridges and lived on restaurants' leftovers. I did it for 6 months. This is the only period of my life I didn’t do art constantly. I met my wife shortly after, and we started a family. I did everything I could to maintain these two things in my life; art and meditation. I tried to sell art online but failed. I tried a community-based approach.

The community around Web3 will do the revolution- at the end of the day this is another medium, and the excitement around this will go eventually. This community is a new and radical change in attitude toward art making. Since I made this move, it felt great and relevant.

Leyla: You have called the time where you were homeless a sort of 'initiation'?

Harvey: Right. I’m quite influenced by Charles Eisenstein, who talks a lot about initiations in terms of native cultures and why they do that, and what function that fulfills. I was living without any money, in food at dumpsters, and living at the bottom of society and that was probably the most difficult part. It was kind of like living like an aesthetic, maybe like the equivalent, like Indian yogis.

Leyla : How does it feel to go from a life on the streets to creating a successful series with collectors and earnings? How do you maintain balance and stay grounded?

Harvey: I'm happily married with a family. My wife keeps me accountable, and we're financially secure now. We haven't changed our lifestyle much, but it gives us the freedom to take risks without worrying about money.

Leyla: Moving on to the Quasi Dragons Studies, can you tell us a little bit about the mechanics of these works? This is not a straightforward drop…?

Harvey: We need to see Quasi Dragon Studies like puzzle pieces. It starts off like a conventional long-form project where people allocated random outputs, joining traits. We can join outputs with sorts like valid joint edges. This is where the community becomes a part of this artwork. We have a composite builder tool, where collectors can take their tiles, or buy extra tiles in the secondary market, and bring them to build new composite artworks in the composite builder- and then mint them.

The end result is that you can just take a single tile and mint that one into the composite collection. Or you can build complicated composite pieces. We have another dynamic where you can follow very strict joining rules; and make these things called ‘black dragons’, which are quite difficult to make. There are 108 one-of-a-kind black dragons that can be created. Once all are made, the project ends, but the remaining tiles can be used to make artwork. I see this as a kind of evolution of pairing, they kind of become merged. The tiles get merged in different ways and you can add to the composites more aspects that reveal other elements. I hope people will enjoy this process.

Leyla: And what is the significance of the number 108?

Harvey: Hundred-eight is an, is an interesting number in many different kinds of Eastern cultures. In a grid of 12 by 12 grid, you have 108 tiles.

Leyla: How about the title, what does it signify ?

Harvey: The elements look kind of like dragons and I love what the dragon represents in some Eastern philosophy; The connection between worlds, between the physical and the transcendental world; being that can kind of fly between heaven and earth.

Ivan: Thanks so much Harvey, super interesting to hear about this. I’d like to know though, how do you keep excited or inspired when working on a series or concept? Which artists inspire you?

Harvey: I find inspiration and engagement in what I'm doing comes from regular work and its discipline, and also from regular appearance of regular periods of silence, of non-activity, like meditation. Creativity is kinda like a habit. And if that's the way you've done for most of your life, that's what you do.

I look at a broad range of arts. I look at Rembrandt and Michelangelo, and Picasso. I am fed by creative energy. I look at musical composers and mathematicians, and people who just have a lot of creative energy.

Peter: How does making art from algorithms allow you to fully express yourself and your artistic practice?

Harvey: Great question. The key to expression is limitation. It's like any language, right? Grammar has rules. If you don't have a structure and limitations, then it's impossible to say anything meaningful. The whole reason I gravitated towards geometry was to just really kind of like create this structure, this grammar, and limitations so I could begin to try and say something with some meaning, you know?

Generative art is just another way of doing that. Another way is working with code. To me, once you get comfortable writing code, the process doesn't feel a lot different for paint the picture. It's still trying to deal with the fundamental problems making, and I think it boils down to being able to look at what's in front of you.

With a totally open mind and just be able to act from your instincts, follow and trust them. I spend a lot of time looking at outputs and thinking what is this asking me? What's this?

Jamie: You mentioned before that your first ArtBlocks project didn't work, and when understanding why, you understood that this is not what collectors are looking for. How do you balance between what the collectors want, and your creative expression?

Harvey: You can be creative within any constraints. It's the same as the limitations I talk about. So those constraints can actually just be what the market likes. We can ensure our audience wants to see or interact with us. I tried for 25 years to create for myself, and when it didn't work it was painful. I looked at what works in Artblocks, and then use that as a starting point to build a project. I look at algorithmic distress on surfaces as produced in an algorithmic way. So I think using algorithms to produce surfaces that look work is true to the medium.

I am increasingly thinking, what is really significant in the space? How can we do something that's really fascinating within Web3? These are the main leading aspects of this project, and what I'm making enables the process and result to feel much warmer and more human.

Jamie: Did seeing how collectors reacted to Fontana versus other projects change your perspective on the work, given your community involvement?

Harvey: Fontana had a big impact on me. It was unexpectedly well-received, and I learned a lot from interacting with the community discussing it. The experience helped me understand their culture and language, and I gained confidence in engaging with them. It was a fortunate opportunity to learn from the art world's unique environment.

Leyla: What do you expect coming out of this new project Quasi Dragon Studies, what would be like the dream scenario that comes out of it?

Harvey: It’s two different; what I expect and what's my dream scenario. So what I expect is I honestly do not know. I’ve tried to design it that way, so it's really hard to predict.

I’ve tried to design it that way, so it's really hard to predict. I'd like this to be seen as a starting point for a new type of subgenera web, where, either myself or other artists can follow this idea. I hoped different algorithms were being composited together and different algorithms from different artists. A collector could look at different artworks from different artists and then create an entirely new one, melding them together. I hope people will enjoy using it.

Ivan: Which incentive do you value more deeply the focus on completing Black Dragons, which results in a smaller supply, or an emphasis on creativity, which would lead to a bigger, more accessible collection?

Harvey: For me, it's gonna always be at first, but I also understand that there's a dynamic at play in web3. Rarity is a thing, traits are a thing.

Ivan: What are your thoughts on utility in general in art and in within web3?

Harvey: I think it's something that helps to build community. I think community is just a fundamental need in humanity. We don't tend to have so many kinds of religion. Certain people are looking for a replacement. They're looking to belong. The real value might be bringing about community and a sense of belonging.

This conversation is a condensed transcript from a Twitter Spaces between Harvey Rayner, Verse and Le Random team including: thefunnyguys, Peter Bauman and Conrad House, which took place in July 2023.

Leyla Fakhr

Leyla Fakhr is Artistic Director at Verse. After working at the Tate for 8 years, she worked as an independent curator and producer across various projects internationally. During her time at Tate she was part of the acquisition team and worked on a number of collection displays including John Akomfrah, ‘The Unfinished Conversation’ and ‘Migrations, Journeys into British Art’.

She is the editor...

Harvey Rayner

Harvey Rayner (born 1st January 1975) is an English artist and creative coder with over 25 years of digital and generative art practice.

He studied at The City and Guilds of London Art School and has had a diverse creative career working as a designer, inventor, programmer, and business owner all while maintaining a dedicated daily art practice.

Rayner's extensive body of work showcases an...