Subscribe to get the latest on artists, exhibitions and more.

Cityscapes: In conversation with Kristen Roos

Mimi Nguyen: Your work spans a wide range of mediums, from electronic music composition to animation and textiles. How do these diverse practices intersect and inform one another in your creative process?

Kristen Roos: All of my work informs one another, and I often create projects with different mediums simultaneously. So, for example, I might be weaving an image that is derived from one of my animated GIFs, whilst listening to a new mix that I’ve made. I think all of my work shares a similar aesthetic and language, and I’m really happy to be in a place in my life where there is an audience that appreciates all of the different mediums that I work in.

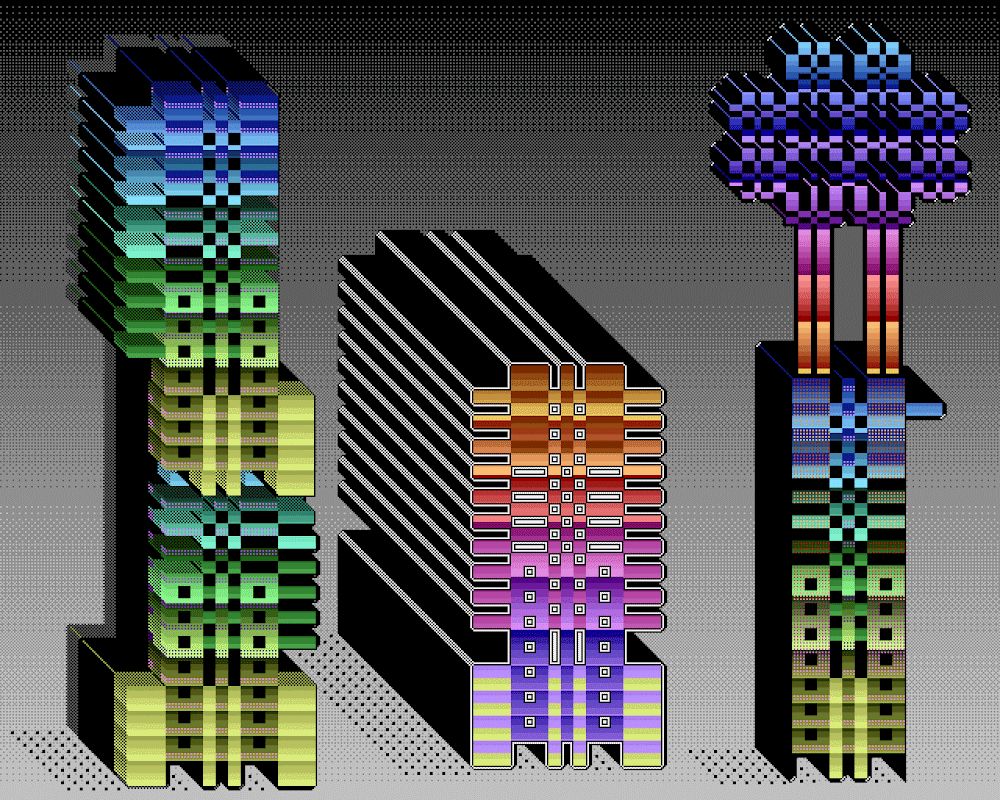

Kristen Roos: My textiles speak about the relationship between computers and weaving. I create my work with a hand operated Jacquard loom. Jacquard Looms are viewed as some of the first ancestors to our modern computers, and they were originally programmed and automated using punched cards. Today the computer takes the place of the punched card with the looms that I use. Since my work is designed with vintage software for early personal computers, and uses traditional weaving patterns and Jacquard weaving patterns from the 1800’s, this has become part of the larger conceptual background of my work. These designs make connections between some of the blocky pixelated imagery created with early paint programs for personal computers and the imagery found in both traditional and contemporary weaving practices. I like to see the connections between work that is hundreds or thousands of years old, and work that is part of a more recent history of screen-based art and imagery that resembles these ancient textiles.

Kristen Roos: Universal Synthesizer Interface, my most recent electronic music project, is a look into the history of algorithmic MIDI sequencing software, and uses software from the 1980’s into the early 2000’s. This project shares similarities with my textiles and animation, in that it has involved a lot of research into vintage software and computers. This audio software is particularly interesting in terms of the current connotations of the word algorithm. The software I’ve used on these albums is part of the first wave of algorithmic MIDI sequencing software for personal computers, and was created at a time when the internet was at its infancy, and social media didn’t exist. The algorithms that now shape our lives through simply interacting with the devices in our pockets, have their roots in the experimental uses of algorithms and computers from this era, as well as further back in the era of mainframe computing.

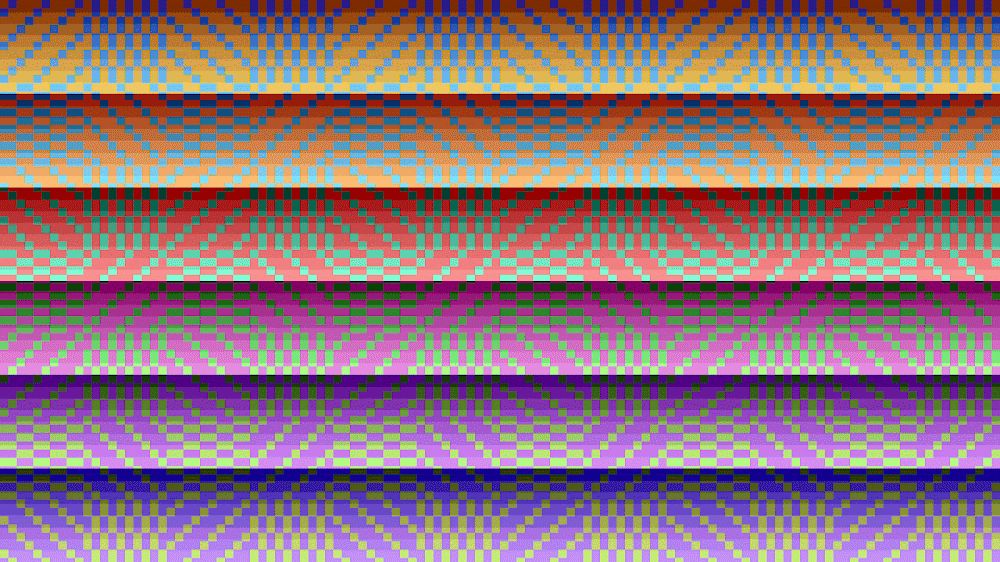

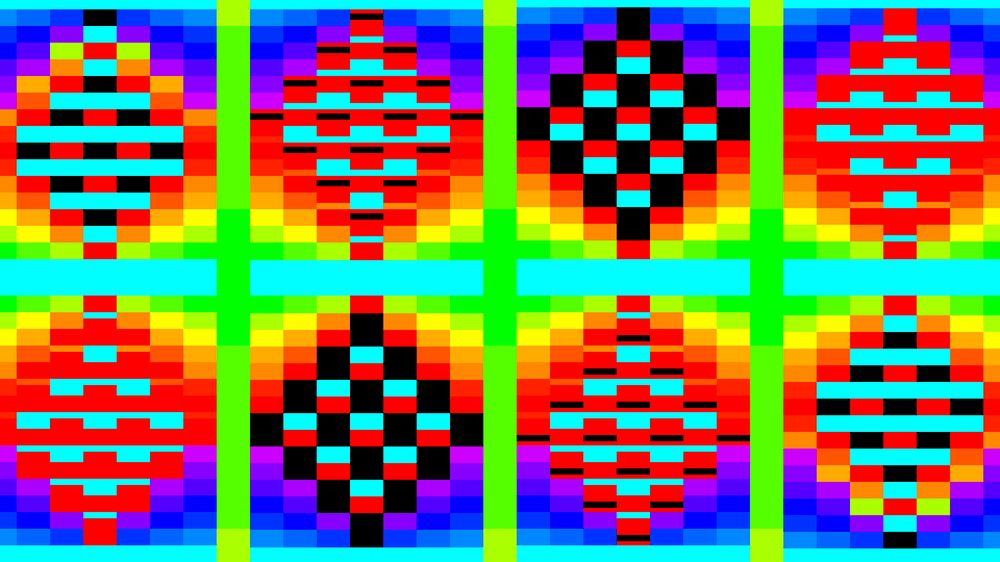

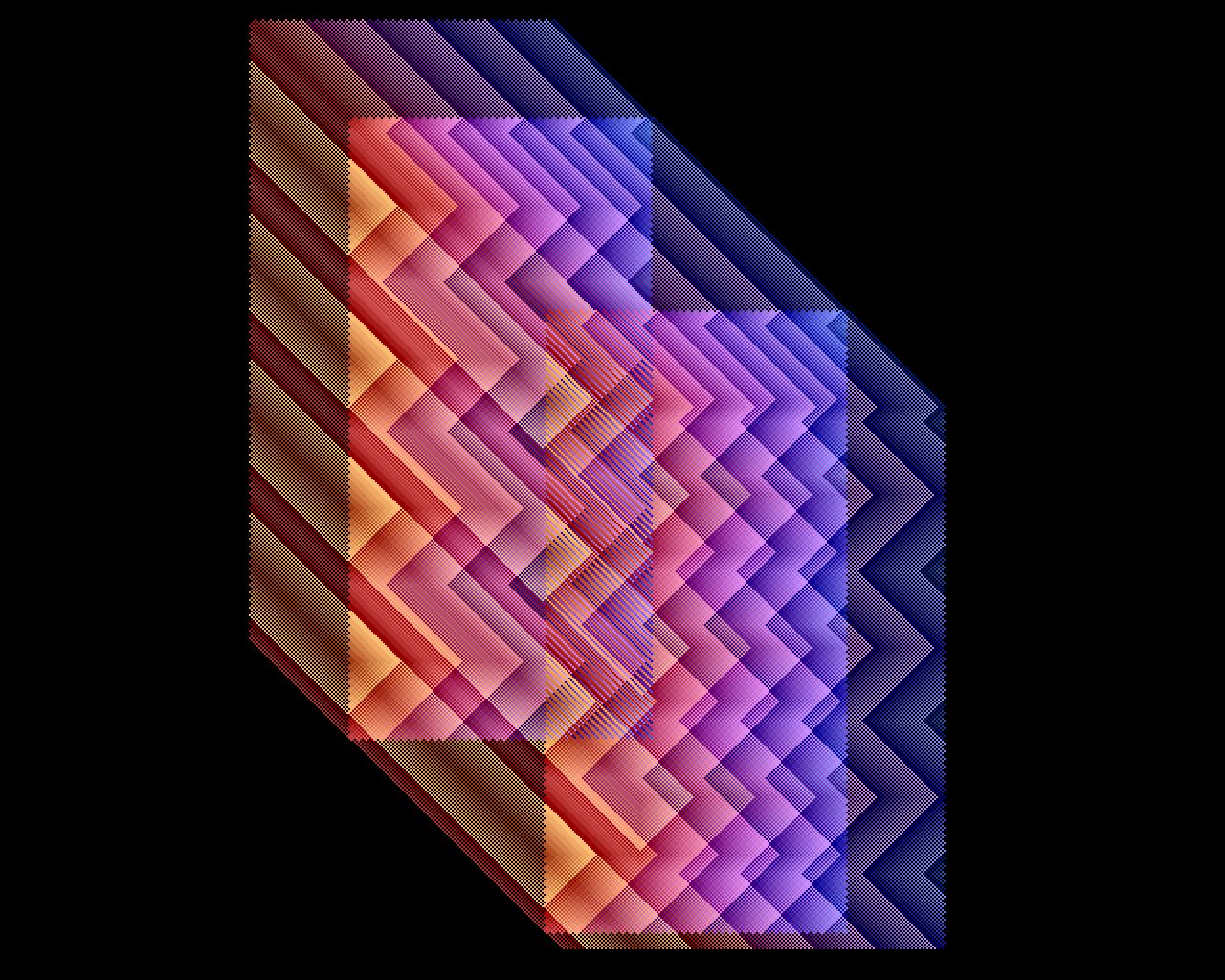

Kristen Roos: As far as the animated work that I create, I can speak about the work that I’ve created for Verse in particular. This work heavily relies on a technique called colour cycling, or palette shifting. This is a technique that goes back to some of the first paint systems for mainframe computers (Super Paint at Xerox Parc), and was eventually adopted by paint software for early personal computers like Deluxe Paint for the Commodore Amiga. This is a way to create the illusion of animated movement with a single still image, by shifting through a specific palette of colours. The palette that is being cycled through can also be looked at as a kind of algorithm, in that one has to define the parameters of the palette, like the number of colours used, and the speed at which the colours are cycled through. This can then get more complex depending on the number of palettes that are being cycled simultaneously.

Mimi Nguyen: Vintage paint and animation software are integral to your creative process. What attracts you to these tools and methods, and how do they contribute to the unique aesthetic of your works?

Kristen Roos: I like the idea of working within the limitations and constraints, and really love the simplicity of a lot of the software that I use, as it allows me to create something deceivingly complex through the use of such limited tools. Constraints are really the major feature of the tools and methods that I use in creating my work, and this really defines the overall aesthetic of the work that I create. Of course, there are also the choices that I make within these constraints, and these choices are very different from how someone else might approach the same tools. But I think that my choices are informed by the limitations of the tools, such as the palette, or what shapes I think work best within these restrictions. This is a very particular way of working, that could be viewed as a kind of homage to the pixel. The work that I create is tied to this square, and interacting with the screen as a gridded, square space. So, the tools define the limitations of the work, and therefore the aesthetic, as I have to create in a very particular way when I interact with them.

Mimi Nguyen: In your previous works, you explored the connection between personal experiences and the screens that define our contemporary lives. How do you see your practice influencing and being influenced by these experiences and screens?

Kristen Roos: All of my work is created using screens, and speaks to the history of the screen – from the televisions and CRT monitors of my youth, to the everchanging range of screens on computers and laptops, to smart phones. I think its important to be aware of this history, especially in terms of my role as a teacher and educator. I think that history is too easily forgotten, and we can see this with the pace that technology has moved just in the past 10-15 years. My work also looks at a bigger picture, and the history of making marks on screens with pixels as something much larger than just the current 8bit nostalgic esthetic.

The origins of digital paint and draw software are part of a larger history of the various labs that provided us with the tools that allow for hand manipulation, drawing/painting on screens with pixels that we take for granted today. We can trace the roots of the tools and the software to the university, military and corporate labs starting in the 1950’s and 60’s, that housed large mainframe computers. Since the tools that came out of these labs were not originally created for artistic purposes, I’m interested in how artistic practices were introduced into these labs, and how this affected the dawn of the personal computer and the graphic user interfaces/screens in the 1970’s. The screen became an interactive and creative space through the personal computer’s entry into the home. This history is inherently tied to the work that I create with hardware and software that was developed for a home market of personal computers in the late 1970’s into the 1990’s. The way that I interact with a screen today, and how I currently create work using screens and pixels contains this history, and makes references to various points in this history.

Mimi Nguyen: Can you tell us more about Cityscapes? Could you elaborate on the inspiration behind this concept and how it manifests in your work exhibited on the facade of SODA in Manchester?

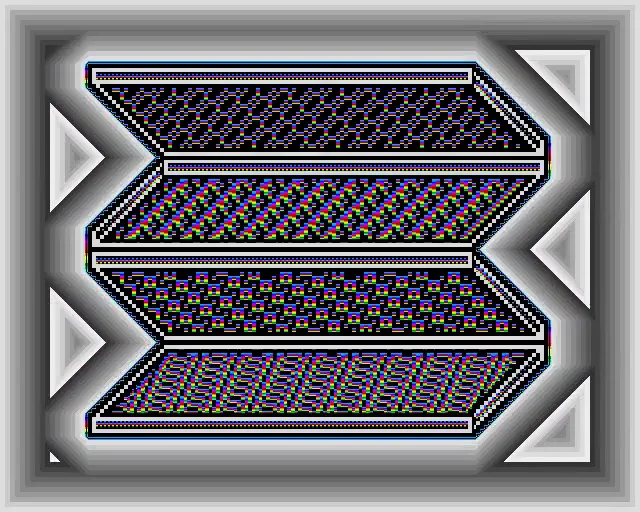

Kristen Roos: When I was first creating my animated cityscapes, I imagined that they may come to life in the future. It was more of a dream that these vibrating patterns might be incorporated into architectural forms. The work that I’ve created for the facade of the SODA building in Manchester has enabled me to think about how these cityscapes can have a real impact on the physical world. This also brings up questions regarding the personal world of the viewer, and the thousands of screens that inhabit this world. We all simultaneously inhabit both a physical landscape and a digital landscape. In creating this work it’s been interesting to think about how these two worlds are connected, and how both worlds are impacted by my work emerging into an architectural form that is both screen and physical structure.

The work that I’ve created for the SODA building is also a response to constraints – the size of the images, and the pixel ratio/depth of each of the facades of the building. All of these limitations caused me to create very particular site-specific work. All of the work that has been minted therefore uses the patterns and shapes that worked well after doing the tests on the building. I’ve elaborated on these shapes, and created new individual structures and larger cityscapes using the work that will appear on the SODA building as source material.

Mimi Nguyen: What do you hope viewers take away from your art, particularly in terms of their perception of the urban environment and the relationship between the physical and digital worlds?

Kristen Roos: I’m not sure if it matters to me that the viewer takes away something in particular, so I can only speak about my own experience with the work. I think it's interesting that my animated work has been so focused on digital space, as a kind of virtual space to create fantastical architecture, and that these fantasies have now become something very physical and tangible in the “real” world. It gives me hope that my work can have many other lives, both in the virtual world and in the physical world. In the end, I just hope that the work provides some joy and inspiration for viewers.

Kristen Roos

Kristen Roos is an artist based on the unceded territories of the TsleilWaututh, Musqueam, and Squamish people, also known as Vancouver. His animated work uses the tools and methods found in vintage paint and animation software. His practice includes a wide range of mediums including electronic music composition, sound design and installation, animation, printmaking, and textiles.

Mimi Nguyen

Mimi is a Creative Director at verse. She is a assistant professor at Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London where she leads the CSM NFT Lab. Her background is New Media Art, having previously studied at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) and Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. She now also teaches at Imperial College London, Faculty of Engineering, where she leads Mana Lab - a “Future...